Honda has a long history of doing things their own way. When everyone else went crazy for two-strokes, Honda (mostly) stuck with camshafts and valves. When everyone else was building twins, Honda built a four. They were the first manufacturer to fit traction control to a motorcycle (on the 1996 Pan European), but the last to fit it to anything resembling a sports bike.

In all its history, Honda has only broken this rule and copied others once. In the late 1990s, after pouring millions of Yen into World Superbike, their 750cc V4 RC45 was still being regularly beaten by Ducati’s big v-twins. Three world titles in 12 years was little reward for a huge amount of factory effort. The rules allowed a twin to be 250cc bigger than the four-cylinder bikes, but Honda’s RC45 (rumoured to be more powerful than even their GP bikes of the time) was losing because the twins had traction, where the fours just had more and more revs.

Changes in WSB rules for 2001 meant that full factory bikes were effectively banned. Nothing could be fitted to the base-model bike that couldn’t be bought in a race kit and the race kit mustn’t cost more than £30,000. Honda’s works RC45 racers were rumoured to cost twenty times that amount and were still getting thrashed, so, in reality, the new rules actually allowed Honda to make an honourable withdrawal of their V4 750.

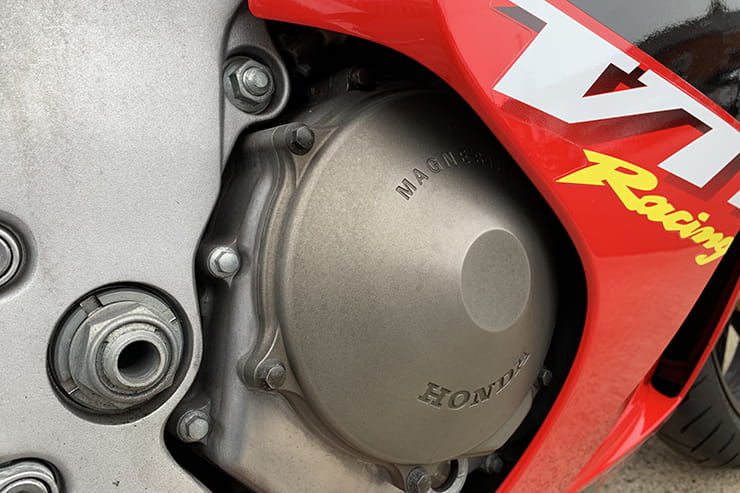

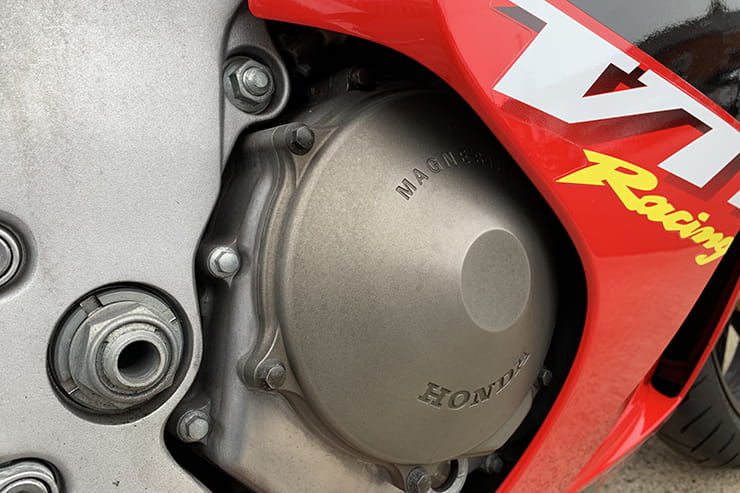

Magnesium engine casings tease at the exotica beneath

At the end of 1999, Honda unveiled their big twin. Built in frustration, to demonstrate just what Honda could do if it wanted to, the RC51 VTR1000 SP-1 was a state-of-the-art racing motorcycle that wore its Honda Racing Corporation stickers with pride. The bike was all-new, owing nothing to the previous VTR1000 Firestorm. Like its HRC predecessors, it used expensive-but-necessary luxuries like gear-driven camshafts. It also had the same careful attention to detail that had made the RC30/45 so special. The SP-1 made more power than the Ducati, had more modern design, but carried a price tag only a little above that of a FireBlade. Not only were Honda looking to humiliate Ducati on the track, but in the showroom too.

The SP-1 wasn’t dainty or pretty like a Ducati. It was purposeful and well-hard. The Ducati might have weighed five kg less but Honda’s insistence that the SP-1 be built as well as its other top-spec machines meant that the SP-1’s exhausts (for example) were built to survive a small war. Watching a customer’s bike blow the innards out of its aftermarket Micron end cans was a very visual demonstration of why this was important.

Build quality was as exquisite as any other Honda of the time

On the track the new SP-1 cleaned up in pretty much everything it entered – from the Daytona 500 to the IoM TT and took the World Superbike crown at the first time of asking, just like the original RC30 had done in 1988. And the first batch of road bikes flew out of showrooms too. Back then Ducatis had a reputation for being quick, nimble, exotic, but fragile and expensive too. Here was an exotic SP Honda, built to last, for sensible money that had Bologna beaten.

The SP-1 was every bit as focussed as you’d expect. The fuel-injection’s throttle response was set-up like a racer - sharp and almost over-responsive. Fine on a track where you are only ever full-on or fully-off the throttle, but not so handy on a salt-strewn slimy B-road in February.

So the first reviews were mixed, also criticising the excessive fuel consumption and stiff, overdamped suspension. Honda’s answer to both criticisms was that the SP-1 was a race bike and their design priorities were all focussed on building a winner. If that meant it used a lot of fuel or lacked rider comfort, maybe you bought the wrong bike. Turns out that while we love the idea of a fire-breathing race bike, when someone actually builds one, we quickly realise that proper racers are very different. This hadn’t been an issue with the RC30 and RC45 because their enormous price tags put them out of most riders’ reach. By making the SP-1 more accessible more of us were exposed to the reality/fantasy gap of playing racers on the road. The other problem for the SP-1 was that Britain was in the middle of a huge discounting war caused by cheap independent imports. In mid-2000 you could buy a Yamaha YZF-R1 (which was a far better road bike than the Honda) for about two thirds the price of an SP-1.

Suspension was firm, well-damped and challenging on a bumpy road

The first batch of SP-1s sold out so Honda UK quickly ordered more stock for later in the year. By the time those bikes arrived, and Colin Edwards had wrapped up the World Superbike championship, everyone who was going to buy one had done so already and Honda UK were stuck with a warehouse full of unsold bikes going into winter. Prices of new SP-1s tumbled. To make things worse Ducati retook the WSB title in 2001. Honda’s response was brilliant. They turned the SP-1 into one of the greatest Honda sportsters ever. The 2002 VTR1000 SP-2 had a few subtle tweaks to the engine, an extra fuel-injector per cylinder, redesigned swing-arm and revised suspension. But most of all it had probably the most beautiful paint job of the noughties. It now rode like a V-twin RC30; smoother (but still not perfect) power delivery, deceptively fast, focussed and on Showa suspension that was so far ahead of the stuff on your mate’s FireBlade it seemed crazy that it wore the same badge. The SP-2 made ordinary blokes from Leeds feel like TT heroes and, following some serious HRC surgery mid-season, it took Colin Edwards to the most thrilling WSB title yet. The VTR1000-SP was back – in racing at least.

It is possible to take a pillion on an SP-1 in the same way as it is possible to play a tune on a tiger simply by pulling its tail. We wouldn’t recommend either.

That was it as far as Honda were concerned. Job done. Development on the SP twins stopped, and all the focus went back on the FireBlade in preparation for its upcoming eligibility in superbike racing. Road bike sales of the SP-2 remained slow (in 2002 Yamaha sold four times as many YZF-R1s as Honda sold SP-2s) and could be bought cheaply until 2006 when Honda stopped importing it (because it wouldn’t pass the Euro 3 emissions regs).

In true soon-to-be-classic fashion prices dropped quickly. Not that long ago you could pick up an SP-1 for £3000 and a tidy SP-2 for not much more. In the last five years SP-2 prices have risen quickly and you’ll currently pay somewhere between £6-10K. It’s the better bike so that makes sense, but in the long run it’ll be the SP-1 that’s worth the money and now is the time to buy one while they are still a fifth the cost of an RC30.

Most of the tatty, doggy ones have been tidied up and put back to standard. Check carefully for signs of it being an ex-club racer or trackday hound. Many SP-1s spent much of 2008-2014 doing just that. A test ride tells all. A good SP-1 pulls strongly and sharply right through the rev range. The gear selection is stiff, but positive and the suspension will feel like your friend when ridden aggressively but kick you back up the arse if you’re half-hearted. Fuel consumption isn’t always as bad as the legend suggests. Typically, you’ll get around 38mpg on a standard bike, but it can be in the low-30s if you get excited.

Fully adjustable front forks work well (but will probably need a service). Brakes are ok, but nowhere near as good as the latest items.

Brakes will feel weak after modern sports bikes because braking development has been immense since 2000. And it will steer much more slowly than you expect, needing a lot more effort than you expect to make it turn. Don’t expect emotion or V-twin character - Ducatis feel much more involving and special. The SP-1/SP-2 is simply a tool for getting the job done.

Check carefully for crash damage and repairs, pay more for standard exhausts and footrests than aftermarket items and check the obvious like handlebar end weights and mirrors (original items suggest it hasn’t been crashed, aftermarket the opposite.)

This stuff matters because the price you are paying has the collector’s value built-in. Without the originality and collectability, it’s just another ageing mass-produced Honda sports bike worth £2350. Remember that before you buy an overpriced hound.

Simple clocks, complex suspension and a special-compound plastic that allowed Honda to make the fairing thinner and therefore lighter

The bike pictured is on sale at Fastline Superbikes on 01772 902600

www.fastline.co.uk

|

Engine

|

90˚ V-Twin, 4-valves per cylinder. Liquid cooled

|

|

Displacement

|

999 cc

|

|

Bore X stroke

|

100 x 63.6 mm

|

|

Power

|

134bhp @ 9500 rpm

|

|

Torque

|

77.4 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm

|

|

Fuel injection

|

PGM-FI electronic fuel injection

|

|

Frame

|

Alloy beam frame

|

|

Suspension

|

Front: 43 mm Showa USD cartridge fork adjustable preload, compression, rebound.

Rear: Showa monoshock, adjustable for preload, round, compression

|

|

Tyres

|

F; 120/70 ZR17

R; 190/50 ZR17

|

|

Brakes:

|

Front: 2 x 320 mm floating discs, 4-piston calipers,

Rear: 220 mm disc, 2-piston caliper

|

|

Dry weight

|

192 kg

|

|

Seat height

|

813 mm

|

|

Wheelbase

|

1409 mm

|

|

Rake (adjustable)

|

24.5°

|

|

Trail (adjustable)

|

100.5mm

|

|

Fuel tank capacity

|

18 l

|

|

Fuel consumption

|

37mpg

|

|

Price

|

£9995 (new in 2000)

£5000-£10,000 (typical) May 2019)

|

Bennetts Insurance for your classic bikes

Back in the old days if you wanted the benefits of classic bike insurance, like agreed valuation, events cover and salvage retention, you’d have needed a bike that was 30 years old. Not anymore. Bennetts insurance for classic bikes could offer all these benefits on newer modern classics, as well as vintage models.

Bennetts are a specialist in motorcycle insurance and have been trusted by riders for almost 90 years. We will search our panel of insurers for our best price for the Defaqto 5-star rated cover you need for your classic bike.

Bennetts Insurance for classic bike comes with:

- NO admin fees for additional bike modifications

- Combine your classic and modern bike on one multi-bike policy

Get a competitive insurance quote »