Some people buy a classic motorcycle as an investment, but for most it’s more about nostalgic indulgence. Middle-aged men are supposed to buy a sports car and run away with their secretary, thankfully most of us buy drum kits or motorcycles and the only running is from the reality of growing old.

The sensible argument is this. If you've got the money…and the space…and the ability to fix them, a shed full of well-chosen motorcycles will pay better than a savings account and be much cheaper than anything involving sports cars, secretaries or divorces. Prices of a classic anything tend to rise, then plateau, and rise again. Get-in early or at the plateau points and you can make money while enjoying the machine of your dreams.

Ducati 916s are currently on the rise, Honda RC30s have plateaued or maybe even dropping in value (selling price, not asking price) and Yamaha RD250/350LC values have been rising again after stalling for a year.

Air-cooled Suzuki GSX-R values (the 1100s especially) continue to rise, while early Honda FireBlades are currently overvalued and anything that was a first bike in the 1980s is getting expensive – even old MZs.

Suzuki GSX-R750 prices have risen by 400 per cent in the last 10 years

We learned from the first wave of classic British motorcycles that everything – even the truly awful - goes up in value eventually. Prices of Yamaha XS750s, Honda FT500s, even Suzuki GSX250s -possibly the least-inspiring Japanese motorcycle of the last forty years - are rising. And this is where the clever (or lucky) money goes.

Honda’s CX500 is a case in point. To most riders a CX is a horrible, slow, ugly, top-heavy motorcycle with slack-handling and poor brakes. But for a generation of couriers they were a faithful friend to be thrashed, dropped, two-wheeled demolition derby’d, mechanically abused and ridden all day without disturbing your embryonic hemorrhoid.

Ten years ago a £500 CX500 was £200 too much. Then those couriers hit 50 and prices rose. Then the hipsters built CX café racers and prices doubled. Right now you pay more for a 1978 CX500 than for a 1998 FireBlade or VFR800. Which is crazy unless you happen to have a shed full of old CX500s for sale.

Honda C90 Cubs are the same. There’s a case for Cubstalgia because so many of us razzed one round a field and get that squirt of gooey nostalgia when we see one. Like the CX, a sub-culture of custom-Cubbing has pushed prices up too.

In order to avoid another generation of mass CX500 ownership, what follows is a simple eight-point guide to buying your first classic. It’s not definitive because this is an emotional, not rational purchase, but it might help you avoid the worst.

Yamaha’s SR125 – clearly the coolest bike in the world. Relive the dream for less than a grand.

1. Choosing a modern classic bike.

For many it’s the machine you rode as a nipper. Memories of that first independent summer, exploring new towns with your mates and meeting new girls who never saw last summer’s ill-advised new romantic experiments.

For others, it’s the poster bikes that we dreamt of but could never afford. Our advice is ignore the poster bikes and buy the tiddler first. It’ll be cheaper and spares will be affordable and easier to track down. Small bikes are usually simple, so there’s more chance you’ll restore it yourself and enjoy the process. Dream bikes are more complex, expensive to buy and restore. They can be disappointing too when you realise how performance, handling and brakes have improved in the last 30 years. Seriously, riding an air-cooled GSX-R1100 in 2019 is awful. Buy one for the looks and the attention, but don’t believe the ‘keeps up with a modern bike on a twisty road’ nonsense, because it doesn’t.

UK-spec Suzuki GS1000s had twin front discs and alloy wheels. This is an American-spec bike

2. Researching a classic bike purchase

Are you sure (if it matters) which is the right model and what the differences were? If your heart’s set on that 1978 MZ’s TS150 then know that, while the TS125 was all-but-identical, they don’t all have a rev-counter and carb settings and ignition timing are different.

Plenty of bikes were independently imported into the UK from overseas and while most are similar spec to a UK bike, there are some significant differences. A Japanese-spec Suzuki GSX-R750, for example, will like all Japanese-market bikes of 750cc and above, be restricted to 77bhp. There’s plenty of knowledge out there on how to derestrict them, but not all ‘Japanese-spec’ bikes coming in from Japan are actually Japanese-spec. In many cases, they were initially exported to another country close by as full-power versions and then re-imported back into Japan to get around the restrictions. Many of the Japanese-spec Honda RC30s Yamaha OW-01s and Ducati 851s are like this.

Easier to spot are some of the American variations. We never got a Suzuki GS750/1000 with wire wheels and single disc brake and we never had the fat-seat factory custom versions that the Americans got.

More importantly, research what goes wrong, what’s tricky to fix and which spares are hard to find. Track down the best owners’ groups, forums and Facebook groups. Don’t forget the general ones as well as specialist make and model ones.

Even better than that, get out there and meet the other owners. By far the best place to do this as a newbie is at one of the big classic bike shows. The biggest is at Stafford, it happens in April and October (October is the one more geared to Japanese and modern classics).

The big classic shows and autojumbles have a huge selection of decent projects for all budgets.

The big shows and autojumbles are also the best place to get an idea of what bikes are actually selling for. Look on eBay and you’ll see inflated prices based on what other crazy optimists thought their bikes were worth. Most of these machines don’t sell and become permanent fixtures on the listings.

At the Stafford shows and jumbles you’ll see bikes on sale at optimistic (but still less than eBay) prices on the first day, but by the second day, the numbers have become realistic. Even if you’re not buying, make a note of what sells and use this information when it counts.

The biggest classic shows and jumbles are run by Mortons Media Group. Their website www.classibikeshows.com has all the details.

Ten years ago (when this pic was taken) you could buy a Ducati 916 for less than £3k and a Honda RC30 for £15k.

3. Setting a budget for a classic motorcycle

How to make a million pounds from a motorcycle restoration? Start with two million. Two years from now you will try (and fail) again to explain to the marriage guidance counsellor, how you spent almost £10,000 buying and restoring a Kawasaki GPz550 that is currently worth £1800 at most.

With a project you don’t need a big lump sum, just enough money to buy the small hedgerow with a rusty motorcycle frame (with log book) sticking out of it and a regular monthly budget to keep the project ticking over till it’s finished. The most cost-effective way of owning a usable classic is to buy the bike that someone else spent time and money on but didn’t finish. The initial outlay will be much higher, but the final cost is likely to be less. Keep money back to sort the problems they either didn’t find or hadn’t happened yet.

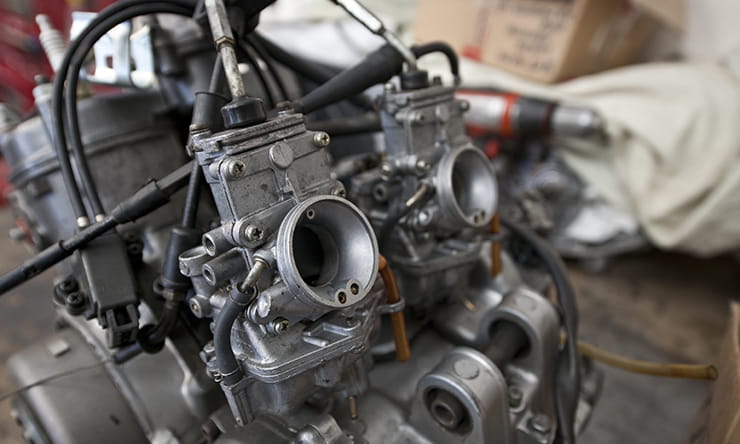

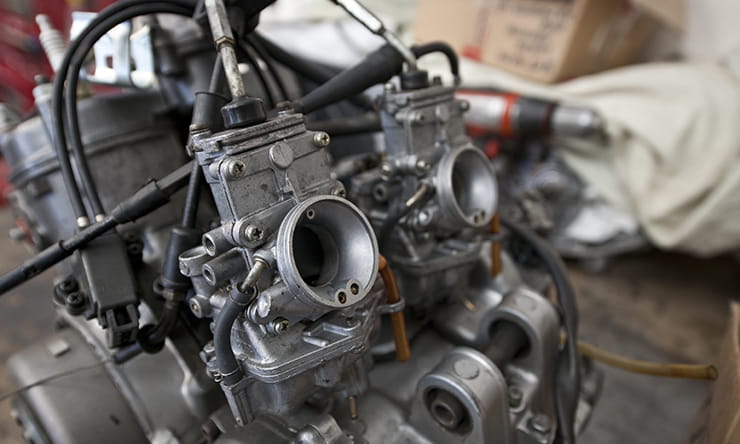

Don’t kid yourself – there’s a lot of work required here

We all over-estimate what we can do ourselves or underestimate the work required. Or realise that the restored the frame, wheels and forks now make the engine look grotty. And maybe we should replace the brakes…and electrics…and rear suspension too. Cue quadrupling of budget.

Some people set themselves a monthly budget rather than a total. Someone I know stopped smoking and vowed to spend his tobacco budget on his bike. It still isn’t finished and he’s still not smoking.

That teeny paint blister is because someone paid a fortune for a respray and then discovered the pinhole in the tank

4. Tidy up or full concours restoration?

Time was that only a full concours restoration would do and the classic world was full of essentially new bikes built around an old frame and crankcases. In British classics this made sense because the bikes were so worn out they needed everything replacing to keep up with a Vauxhall Corsa. Japanese classics were more reliable to start with, but you’ll still want the engine and electrics serviced, plus the carbs cleaned too. The carbs will also need rejetting to…

Allow for the differences from the new aftermarket exhaust you sourced

Allow for replacing the nasty aftermarket pipe and air filters with a standard exhaust and airbox

If it’s been standing for a while, you’ll need to replace the fuel pipes, fuel tap seals and anything else in contact with the ethanol in modern fuel. There will either be a small rusty pinhole in the fuel tank or about to be one where, rust, caused by the water in the ethanol is eating your about-to-be resprayed paintwork.

Suspension and brakes will need reconditioning with fresh seals, new fluids and careful elbow grease. And the brittle snap-fest that used to be a 1983 wiring loom and connectors will need renovating too.

Some people replace with uprated parts from more modern bikes. Originality means less when the bike is still worth relatively little and there’s plenty of time to put it back to standard in 2025 when the price skyrockets. So, make sure you save the original parts when you fit the Aprilia RSV-R front end to your Bandit 1200 because one day you’ll be glad you did.

Websites like eBay are easy, but a wanted ad in the classifieds is still surprisingly effective

5. Finding the perfect modern classic bike

The easiest and probably least-used way to find your classic is to put a wanted ad in among the classifieds or on the appropriate facebook groups and forums (the classic bike magazines are good for this and ads are usually free). Make it clear you are a genuine private buyer, say exactly what you are looking for (but not how much you want to pay) and wait for the phone to ping. By saving the seller the hassle of advertising it you are in a strong position to set a reasonable starting price.

Pricing a classic is tricky. Everyone in the classic world watches eBay all the time, so everyone knows what’s out there and how long it’s been unsold. The biggest problem valuing a classic is that the condition of the bikes vary so much. Some are immaculate and unrestored, others are concours restorations or tidy, running examples. And then there are the projects. How many different versions of ‘needing restoration’ can you think of?

Chances are the classic bike you are buying was the seller’s dream bike too, so you have their emotional as well as economic investment to overcome. They will tell you how their Suzuki RGV250 is the only one that was never raced, despite all the evidence to the contrary that you can spot at 50 yards. It is apparently worth more than that expensive one on ebay, despite that bike remaining unsold for six months.

If you’re after a Segale-framed Honda, chances are the first one you see will be the only one.

Your job is to present evidence of what similar machines are going for, point out the shortcomings or work still needing doing and then knock another chunk off the price for the hassle you are saving them for their quick sale.

This is the moment when all that research paid off. You know what to look for, how to spot an American-spec bike, what a genuine engine number/exhaust system/brake disc looks like. You know that white and blue ones sell for more than black and orange ones and that the 1987 models had issues with valve seat recession so low mileage Japanese imports should be avoided because of this and the potential restriction, unless very cheap.

Ask all the really important questions before you go to view, or you’ll spend a fortune on petrol and wasted weekends on the M6 looking at overpriced rusty mutton dressed as lamb.

Easy project, 90% complete

6. Decoding the classic adverts

Adverts for classic bikes are harder to read than those for modern bikes. There’s considerably more fluff, a lot more emotion, factual inaccuracies and flowery language masking a whole load of problems.

What follows is only partially tongue-in-cheek and represents a starting guide to decoding the classic ads.

|

What they say

|

What they mean

|

|

Rare bike

|

No one wanted it in 1985 either

|

|

Good investment

|

Can’t possibly depreciate any more

|

|

Easy restoration

|

Took it to bits, haven’t lost many parts

|

|

90% complete

|

Took it to bits, have lost too many parts

|

|

Just needs carbs setting-up

|

Tried everything, still won’t run properly

|

|

Rare colours

|

It’s not brown/beige, it’s urban tiger

|

|

One-off paint scheme

|

It’s been crashed

|

|

Polished frame

|

It’s been badly crashed (or stolen)

|

|

Needs engine work

|

Was seized, but I freed it off

|

|

Rebuilt engine

|

New spark plugs

|

|

Turns over but we haven’t run it

|

Because it needs a full rebuild

|

|

One owner

|

Can’t sell it

|

|

Many new parts

|

Always breaking down

|

|

Will sail through MoT

|

No it won’t

|

|

Low mileage

|

New clocks fitted

|

|

Tuned engine

|

Doesn’t run right

|

|

No offers

|

That’s why it’s still for sale

|

|

Lost the V5

|

It’s stolen

|

|

Selling for a friend who…

|

|

|

…Has moved abroad

|

It’s stolen

|

|

…Doesn’t have eBay account

|

It’s stolen

|

|

…Doesn’t have computer

|

It’s stolen

|

|

…Is working abroad

|

It’s stolen

|

‘Immaculate, concours bike. Matching numbers…if you have a stamping kit’

7. Checking the history of a classic motorcycle

The hardest (and most-often forgotten) part of buying a classic motorbike is checking the history correctly.

Expert rebuilds are expensive but worth every penny

8. Use an expert or do it yourself?

If you have the space, tools, time and some mates whose brains and muscle you can borrow, restoring a bike is straightforward and satisfying. You’ll need specialist help at some point, because they have specialist equipment that you don’t have. However, you don’t have to powder coat the frame, you could just paint it – like the original was. You don’t have to respray the paintwork, rechrome the forks and engine casings or rebuild the engine if it runs ok at the moment.

It all depends whether you want the bike because you simply want one or is it more than that? Do you have that competitive need to be recognized as ‘King of the Kawasaki Z440 LTD Club’? If so, accept your ego and enjoy the ride.

Very few expert services cost a fortune and because most of the specialists are as passionate as you, they’ll do their best to help. If you take your two-stroke engine rebuild to the most legendary tuning guru, he’ll charge you accordingly, in the same way that if you wanted the actual Led Zeppelin to play at your birthday party, you’ll pay more than French tribute Le Zeppelin.

Away from those specialists you could argue that for the general stripdown, tidy-up and rebuild, spending the few hundred quid you would have spent with a mechanic on some decent tools, a proper bike bench and a soldering iron will give you more control over the project, a lot more satisfaction and will set you up nicely for doing your next restoration too.

Brilliant. Well done, I’m very jealous. Because I have the mechanical aptitude of an impatient drummer and a house with no garage. So when I restored my Yamaha TDR250 I gave it to Gary Horton at Classic and Restoration in Droitwich, who did a terrific job, could cunningly restore seemingly knackered parts to help keep costs down and was patient and easy to deal with.

Knowing your limits is a good thing.

Living the dream, while listening for rattles and clunks

9. The shakedown.

Your project is finished. A fresh MoT, classic insurance, tax and sunshine too. Time for a ride. As a sensible, grown-up you’ll appreciate that the Honda factory knew a lot more about putting a motorcycle together than you and your brother. They wouldn’t have routed the clutch or throttle cables badly or over-tightened the steering head bearings, trapped the fuel line between the tank and the frame or forgotten to torque up important fasteners (unless your bike is Italian or British or American, in which case all the above do actually apply).

So, your first few rides should be a shakedown; take your time, keep distances short and be gentle to let things bed-in. There will be problems and things will come loose or fall off. Some restorers leave re-painting till after the rebuild because they know the tank and fairings will be off and on many times in those first few weeks.

This is when you discover the new uprated forks from a later model are too stiff for the bendy frame or the bike now sits at the wrong angle on its wheels and steers too quickly and tankslaps. Or that the racing carburetors you fitted don’t work below 6000rpm or in the wet, or with the standard ignition timing and £1000 race exhaust you fitted too.

None of these are serious, but take time and money to sort out. This is the stage when projects get sold – it’s also the best time to bag a bargain if you’re lucky.

The next generation of classics will be the bikes ridden by or dreamed of by motorcycling's 'class of 97'. The boom in riders that arrived via Direct Access testing, stayed for a few years and moved onto posh mountain bikes. When these guys hit the big Five-Oh in a few years time we'll see prices of Suzuki Bandits, Honda Hornets, grey import 400s and Aprilia RSV1000s go through the roof.

Good luck, and don’t forget to enjoy it.

Huge thanks to Mortons Media Group for use of the photos from their Stafford Show

Bennetts Insurance for your classic bikes

Back in the old days if you wanted the benefits of classic bike insurance, like agreed valuation, events cover and salvage retention, you’d have needed a bike that was 30 years old. Not anymore. Bennetts insurance for classic bikes could offer all these benefits on newer modern classics, as well as vintage models.

Bennetts are a specialist in motorcycle insurance and have been trusted by riders for almost 90 years. We will search our panel of insurers for our best price for the Defaqto 5-star rated cover you need for your classic bike.

Bennetts Insurance for classic bike comes with:

- NO admin fees for additional bike modifications

- Combine your classic and modern bike on one multi-bike policy

Get a competitive insurance quote »