Modern classic Monday

Honda VFR750R RC30

Everything you need to know by someone who used to own one.

There’s an awful lot of guff talked about Honda’s RC30 so, before we go further, here’s the four things you absolutely must know.

- A Good RC30 on proper modern tyres is still an incredible experience to ride. The throttle response, engine note and pinpoint accurate steering are unbelievable for a bike that is older than your First Guns and Roses album

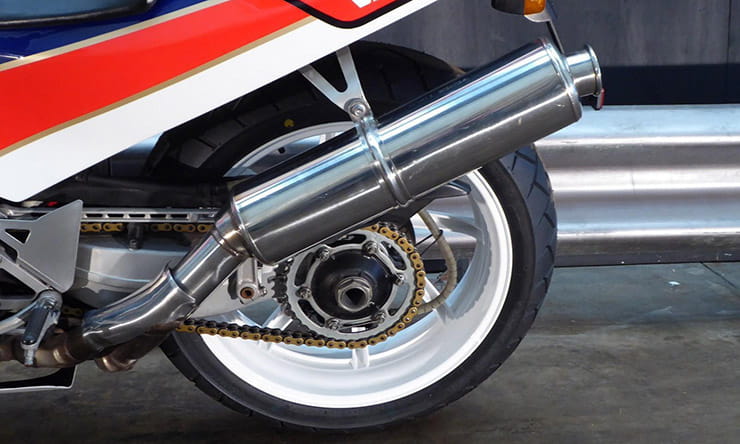

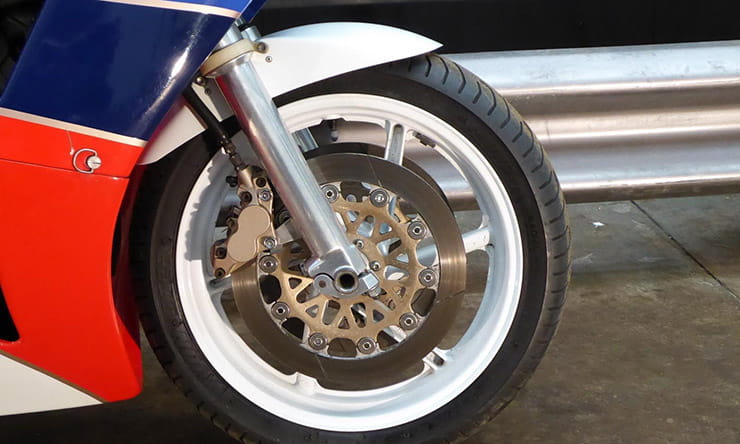

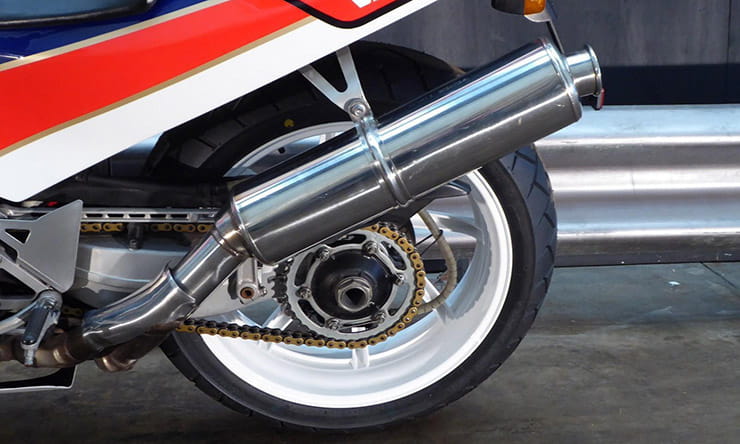

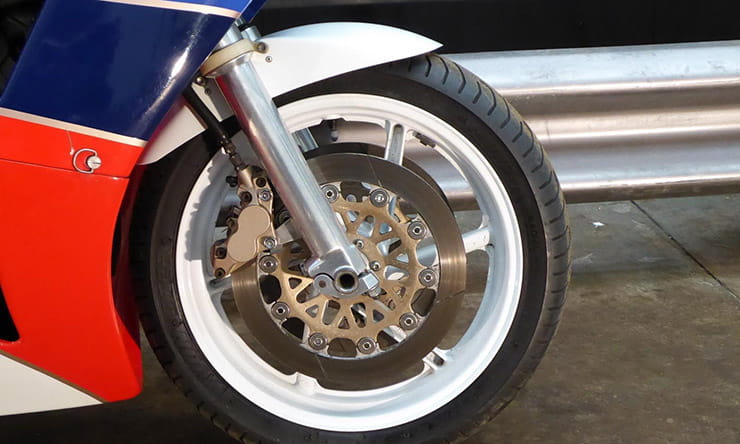

- Once you own one you’ll rarely ride it as you want to because there are no modern sports tyres available, meaning you’ll be paranoid about crashing it. Replacement bodywork is non-existent, as are exhausts, handlebars, lever and fork legs. The best rear tyres available in the RC’s 170 width on an 18in rim are a Dunlop Roadsmart 3 or Bridgestone BT54. Harley’s 2002-model V-Rod used an 18-inch wheel in a similar width and a radial tyre in a 180 section, so tyres for that bike might be ok.

- Once you have the tyre, you’ll be paranoid about the engine overheating. The RC30’s marginal cooling system and compact packaging were designed to lap the IoM and Suzuka. Where traffic lights and filtering are less of an issue. You’ll also become paranoid about the oil consumption and when the engine was last properly serviced, whether it has been well tuned (ex-racer) or properly derestricted (Japanese import).

- Because of the above it’s much, much better to buy a regularly ridden, higher mileage RC30 than a low-mileage show pony. Even better, buy a good condition VFR400 NC30 and thrash the thingies off it. The experience is ninety per cent as good, without the paranoia.

‘I’d love to own and RC30’ said me and pretty much every other sporty rider at some point.

‘So, what’s stopping you?’ came the reply. This was mid-2001 and I was doing a magazine feature where we compared a 13-year-old RC with a 13-month-old Suzuki GSX-R1000. Both bikes were worth about the same money (£7k back then), both weighed about the same amount, but the Suzuki made fifty per cent more power (and then some), had state of the art fuel injection, chassis design, suspension and brakes and was the current hottest-poopest sports bike.

I blustered to the RC’s owner about not being able to afford it, not being able to find a good one and more lame excuses. His response was that interest rates had rarely been lower, anyone with a job and a half decent credit rating could afford a loan for £7k and by the time you’d paid it off the bike would be worth at least £1000 more anyway.

He was right, so I did. Expert advice was invaluable; take your time, don’t be afraid to buy a Japanese-spec import and don’t buy the first one you see because there are enough good ones out there if you’re patient.

I looked at six bikes before buying mine. Two were recently painted ex-race bikes, with sellers pretending otherwise (or maybe they didn’t know). The next was an ex-TT racer, back on the road for the last nine years with a box full of proud press cuttings, but a dent in the frame, badly stamped frame number (worst case… nicked, best case…smashed to bits and a new frame needed – which come unstamped) and pulled to the right when I took my hands off the bars.

Fourth and fifth bikes were like the first two. I was starting to get wise now, learning to spot the signs quickly. The most obvious is to look at the gap between the screen and the fairing. Bikes with replacement screens or bodywork have a gap, original items are perfectly flush. Most RCs have been repainted because the construction of the panels and materials used means the paint blisters.

That’s fine, but don’t try and then charge me top whack because it’s original.

The sixth was still in race trim, but half the price of the others (£3300 in 2001) and very tired.

The last one, the one I bought was a low-mileage example of a Japanese-spec bike previously owned by a guy who worked at Harris Performance who had fitted Ohlins suspension and had it set up beautifully and running spot-on. £6000 and it was mine.

Japanese-market RC30s were the first 1000 built. When first announced in summer 1987 there was a draw for eligibility to buy one. The first bikes had a numbered plaque on the frame and a special key with the logo on a carbon fibre inlay. They also had small headlights like the VFR400R NC30 and were restricted to 77bhp like all 750cc Japanese-market models.

Back then manufacturers produced different specs for different countries. The French and Germans had a 100bhp restriction, Switzerland was similar to Japan, but the rest of Europe got the full power bike. Back then it didn’t matter to us, but as demand in the UK for secondhand RC30s grew, more and more bikes from abroad have been imported so make sure you check whether yours still has the restriction.

As a bike journo I was lucky enough to have some contacts at Honda in Japan and I shamelessly quizzed them for details on de-restriction. They told me that the main restrictions were in the CDI unit and silencer but because of the nature of the bike, pretty much every Japanese owner would have covertly derestricted them anyway. Their suggestion was to run the bike on a dyno and if it made somewhere in the low 90s bhp it was a good-un. Mine made 93bhp.

Owning an RC30 is amazing, for a while. Opening the garage door and seeing it there, every morning is one hell of a way to start the day. The engine is still astonishing. Not just because of the big-bang firing order that generates the maximum forward motion and traction from every single spark. Not just because of the noise it makes from the standard pipe or that it was the first production bike to have a slipper clutch either.

The main reason the engine dominates the experience is that it allows you, the rider to be in absolute control. The relationship between throttle and rpm is perfect, making you feel able to dial in the exact rpm you need anytime you want to. The gearchange is beautiful too and the way it steers and holds the road when all around it is in utter chaos is like a slo-mo scene from some crazy action film where our hero, seamlessly dodges bullets and slides through the danger.

This was Honda showing the world exactly what it could build when the accountants went home early. Ride one back to back with any of it’s WSB homologation special rivals and they all feel not-quite finished, a bit cheap and waiting for that last ten per cent of development. The way a good RC30 demolishes a British B-road gives even halfwits like me an insight into just how good it must have been around the IoM TT.

The first year I had it I did 2000 miles. Track days, trips to the Dales and even researching a gruelling 440-mile test route for the magazine I worked on at the time. Every ride was memorable; as a fast road bike it still felt special because the RC was a bike built without road compromises, to simply perform. Yes, it really was a roadgoing version of the all-conquering RVF racer. Built to compete and win in the many emerging four-stroke race series, the RC had to be as good in WSB as it was in F1 or the TT or Suzuka. It didn’t have to win magazine road tests or have a jaw-dropping spec sheet. The irony was that when launched no one noticed that the most important number was that it weighed 25kg less than the competition, which was far more important than how much power it made.

The ride quality from the Ohlins on mine was superb, the sensation of being tucked-in to that almost perfect riding position was always special – like hugging an HRC-built thermonuclear device.

The second year I started to worry about oil consumption. It used half a litre every few hundred miles, which was typical for an early RC. They all use a bit because of the racing piston design, but early ones had an issue with valve seats and it was likely mine hadn’t been sorted.

I also had the weird experience of not riding a bike because it was too sunny outside. RC30s have two tiny radiators, designed to work lapping the IoM at 120mph, not getting caught in the Nottingham rush hour. It ran so hot my legs, wrapped in too many kilos of Crowtree’s finest cowhide, felt like they were on fire.

The killer for me was when I had to go to the British GP in the car because the forecast was too warm to risk the RC in the queues of bikes going in and out of Donnington.

Shortly after, I sold my RC30 for a small profit. Buyers were fussy when they found out it was the Japanese model, but the bloke who bought it knew exactly how good it was. Shortly after that, prices of even bad RC30s sky-rocketed. These days you won’t find even a tatty standard one for less than £20k. If you can afford it, then buy one, because in ten years’ time it’ll be worth 50 per cent more. If not, don’t worry. Buy an NC30 instead while they are still affordable and easily restorable.

Honda VFR750R RC30 specs

|

Price

|

£20,000- £35,000

|

|

Engine

|

748cc, liquid-cooled, 16v, V-four

|

|

Power

|

112bhp @ 11,000rpm (claimed)

|

|

Torque

|

54 ft-lb @ 9800rpm

|

|

Frame

|

Alloy, twin-spar

|

|

Tyre sizes - Front

|

170/60/VR18

|

|

Rear

|

120/70/VR17

|

|

Suspension

|

|

Front

|

43mm forks, adjustable preload, compression and rebound. 120mm travel

|

|

Rear

|

Monoshock, adjustable preload, rebound and compression 130mm travel

|

|

Brakes

|

|

Front

|

Twin 310mm discs, four piston calipers

|

|

Rear

|

Single 220mm disc, two-piston caliper,

|

|

Wheelbase

|

1410mm

|

|

Seat height

|

785mm

|

|

Fuel tank capacity

|

18 litres

|

|

Wet Weight

|

185kg dry

|

|

Top speed

|

155mph (est)

|

|

Fuel consumption

|

41mpg (tested)

|

Bikes in photographs on sale at Extreme Trading, Norwich, who specialise in importing rare motorcycles. They don’t have a website, but you’ll find them on ebay or on 08082810425

Bennetts Insurance for your classic bikes

Back in the old days if you wanted the benefits of classic bike insurance, like agreed valuation, events cover and salvage retention, you’d have needed a bike that was 30 years old. Not anymore. Bennetts insurance for classic bikes could offer all these benefits on newer modern classics, as well as vintage models.

Bennetts are a specialist in motorcycle insurance and have been trusted by riders for almost 90 years. We will search our panel of insurers for our best price for the Defaqto 5-star rated cover you need for your classic bike.

Bennetts Insurance for classic bike comes with:

- NO admin fees for additional bike modifications

- Combine your classic and modern bike on one multi-bike policy

Get a competitive insurance quote »