If you’re considering buying your first air-cooled classic bike, then a Morini 3½ deserves a place on your shortlist…

…unless of course you are ten foot tall, in which case the ‘pocket-size superbike’ (as the headline writers of the 1970s insisted on calling the Morini) may be a tight physical fit. It’s an easy call: if your tastes tend towards adventure-sports modern motorcycles then there are plenty of other old bikes which will fit your frame (check out the BSA-Triumph range from 1971/72, for instance). The Morini V-twins are an obvious option for people who prefer café racers and middleweight roadsters.

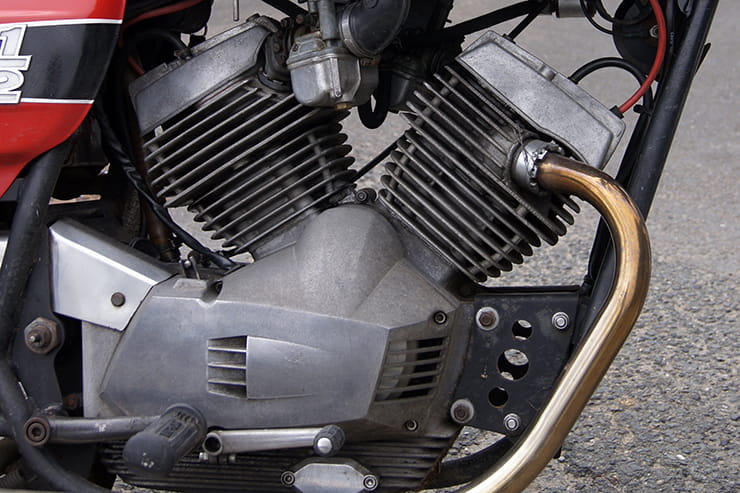

The machine you see here is a 1977 Strada model, owned by the Morini Riders’ Club – one of those enthusiastic organisations which offers invaluable expertise, information and owner support. Don’t be misled by the term ‘touring’ which is applied to the Morini Strada. In classic motorcycling this is a relative term applied to bikes which are slightly less uncomfortable and a little bit slower than their sporting siblings, and that’s pretty much the case with the Morini 350s. In effect, the Strada can carry a pillion while the Sport is set up for solo riding – but after four decades you’ll be unlikely to clap eyes on a standard one so any example you inspect is likely to have been adapted to its most recent owners’ requirements.

In practical terms, the Morini 350 twins provide much the same performance package as the current generation of 300 singles – about 35bhp and 155kg – and they fulfil a similar role to the Honda CB300R and BMW G310R. Except the Morini does it with an infinitely superior soundtrack… and the mixed blessing of mechanicals which an owner can actually fix, but which may require you to do just that. Still, you wouldn’t be looking to buy a classic bike if you weren’t prepared for both ‘character’ and ‘involvement’. Would you?

Price

The Morini 350s were painfully expensive when new: more than 50% on top of the cost of a Suzuki GT380 or an RD350. These days they can be fairly affordable by classic standards. The later bikes (cast wheels, disc brake, better gearbox, electric start) typically cost less and you’ll find fair examples for £3000.

A really tidy, pre-1978 wire-wheel 3½ comes with a £5k price tag and some collectors will spend up to £8000 on a top-spec, perfectly prepared Sport. Machines fitted with ugly-ass non-standard exhausts or the wrong headlight are worth less: upgrades worth paying for include twin discs and modern electronic ignition.

Power and torque

The Strada engine runs at lower compression with a different cam to the Sport which means it’s 4bhp down on ultimate power and slightly slower off the stops. Even so, it’s no slouch and can be pushed to 95mph on track – and yes, plenty of Morini owners regularly thrash their 35 year old 350s at track days. In road use, the Strada is perfectly happy to cruise at motorway speeds in reasonable comfort, although some vibration may be apparent. Back in the day, the Strada was 10mph down on the Honda CB400/4 but the twin is almost 100lb lighter than the four. On any single-carriageway road, the Morini will feel as fast as the 400.

You’ll get from standstill to 60mph in around six seconds; peak power is developed at just over eight grand, while torque tops out just below 6000rpm. By modern standards this is reasonably low revving but for a classic, air-cooled V-twin these are quite high numbers. Riders familiar with Japanese fours will find the Morini motor pleasingly punchy: owners of older British twins who never rev past 4000rpm might wonder what all the fuss is about. Give it serious stick and rediscover the peculiar pleasure of using an engine to its absolute maximum: flat-out in fifth pretty much epitomises the entire point of a Morini 3½.

Engine, gearbox and exhaust

The Morini V-twin engine is simple to maintain and quite remarkably robust. 75,000 miles isn’t at all unusual if the oil is changed frequently (don’t forget to clean the gauze oil strainer) and the cam belt replaced every 15,000 miles. We know of one well-maintained machine which has done 225,000 miles and is still merrily rasping around. Motors run best on higher octane super-unleaded petrol. Poor starting, running or charging can be due to old alternator rotor magnets.

The gearchange and clutch are usually light and precise. The revvy nature of the engine means you’ll be zipping up and down the six-speed box to drag it out of the ‘docile’ dept (below 4000rpm) and into interesting territory above 6k.

Several classic specialists offer original-style, stainless steel downpipes and silencers – they’re not cheap, but they’re a damn sight easier on the eye than some of the hideous siamesed contraptions which were fitted in desperation a couple of decades ago.

Handling, suspension, chassis and weight

Unlike most classic V-twins, the Morini motor has a relatively narrow, 72-degree angle. This contributes to the bike’s 54” wheelbase (similar, again to that of the modern singles we already mentioned) and gives it the nimble steering for which it’s famed. The ride is typically quite firm, unlike most Japanese machines of the time, and the steering geometry is spot-on. So a 1977 Strada will run rings around its contemporary Honda 400/4.

The Morini’s Marzocchi front end was originally set up stiff, as was the way with most Italian bikes of the time. Softer springs are an obvious option, if you can live with slightly less precise steering. Progressive springs can make the ride more comfortable but owners report reduced roadholding. Better to check that the springs themselves are in good nick and the fork oil is clean; using heavier / lighter oil provides limited influence compression and rebound damping.

Originally the Strada’s rear end was supported by a pair of Paioli shocks while the Sport got stiffer Marzocchi springs. For regular track use, owners typically opt for replacement shocks with higher heavy spring rate and about three inches of travel. For a softer ride on pot-holed roads, lighter springs with 3.5” travel come recommended. Progressive springs on the Morini tend to be a compromise that suits no one particularly well – better to specify a spring rate to suit your weight and riding requirements.

With fuel, the Strada weighs in under 160kg – once again, comparable to a current single-cylinder machine.

Brakes

Our featured machine might’ve been first registered in 1977 but it was built to the 1976 spec which means it kept the ‘classic’ wire wheels and drum brakes. Cast wheels and discs arrived for the 1977/78 model year. In practice, the first disc brakes aren’t a massive improvement over the Strada’s 200mm, single-sided twin-leading-shoe stopper when it is correctly set up. It’s worth chamfering the leading edge of new shoes to provide progressive action, and then adjust the brake a couple of hundred miles later, after the shoes have bedded-in.

You can upgrade to the Sport’s 230mm double-sided drum; when new this would stop the 350 from 30mph in 28ft while the Strada needed 31ft to come to a halt. Pretty good for their time, but you’ll need to keep your distance from ABS-equipped vehicles these days – and bear in mind that those stopping distances are for both brakes. If you’re used to a 4-pot fully-floating dual-disc front stopper then you’ll need to apply a lot more rear brake on a Morini.

Comfort

Both 350s are frequently suggested for smaller riders, thanks to the combination of light weight, slim saddle profile and low seat height which makes them easily manageable. The Strada differs from the Sport with its higher handlebars, mid-positioned footpegs and dual seat. These give the Strada a more upright and relaxed riding position that can accommodate taller riders.

Equipment

Electric starting arrived with K2 models in 1985; before then you have to fire it up with your foot. That’s no big deal with this 350 twin – it typically needs a couple of firm prods to get the engine spinning, not the old Britbike ‘long swinging kick’. However, the kickstart lever is located on the left which takes some acclimatisation. No problem when you’re parked, but a bit tricky if you stall in traffic.

Similarly, the foot controls are laid out a la British bikes, with the gear lever on the right and the brake pedal on the left. Using the ‘wrong’ foot to change gear requires some practice to achieve slick shifting.

Unlike many European motorcycles of its era, the Morini is blessed with a sensible, solid sidestand that doesn’t flip up at inconvenient moments. It’s usually accompanied by a reasonably robust centrestand. On the downside, the 3½ is equipped with some of the worst switchgear you’ll ever encounter on a motorcycle. Hence why indicator signals from Morini riders can be quite erratic. And while the engine, chassis and suspension are all reliably robust, the original electrics are not – seek out an example which has been recently rewired and fitted with modern components.

1977 Morini Strada verdict

While claims that it could out-perform a 750 were quite possibly just a tiny bit over-stated, it’s true that the Morini 350 V-twin packed the poke of an (old) 500 into a compact chassis with rewarding roadholding. It’s one of those rare motorcycles which a keen rider can use to its absolute max. The overhead valve engine is straightforward to maintain; spare parts are in good supply. The Strada is a better all-rounder than the Sport, and not significantly slower in road use. It’s characterful, quirky without being downright weird or overly complex and, as such, genuinely represents an ideal introduction to older motorcycles.

Three things I loved about the Morini Strada

• Solid sidestand

• Eager, energetic engine

• Responsive, precise steering

Three things that I didn’t…

• Left-side kickstart makes re-starts tricky

• Carb-mounted choke lever is a right faff

• Ignition key awkwardly positioned under leg

Links

Morini expert Paul Compton has shared stacks of essential maintenance vids on his YouTube channel: www.youtube.com/user/EVguru/videos

The Morini Riders’ Club hosts a cracking track day each year and is an owner’s top resource for technical info and expert advice: www.morini-riders-club.com

1977 Morini 3½ Strada spec

|

New price

|

£850

|

|

Current value

|

£5000

|

|

Capacity

|

344cc

|

|

Bore x Stroke

|

62mm x 57mm

|

|

Compression

|

10:1

|

|

Engine layout

|

72-degree V-twin

|

|

Engine details

|

Air-cooled ohv four-stroke

|

|

Power

|

35bhp @ 8200rpm

|

|

Torque

|

24lb-ft @ 5900rpm

|

|

Top speed

|

95mph

|

|

Carburetion

|

2x 25mm Dell’Orto VHB 25BS

|

|

Transmission

|

6-speed, chain drive

|

|

Average fuel consumption

|

70mpg

|

|

Tank size

|

3.5 gallons

|

|

Frame

|

Welded tubular steel duplex cradle

|

|

Front suspension

|

Marzocchi tele forks

|

|

Rear suspension

|

Swinging arm, 2x Ceriani shocks

|

|

Rear suspension adjustment

|

5-way preload

|

|

Front brake

|

200mm tls drum

|

|

Rear brake

|

180mm sls drum

|

|

Front tyre

|

3.25 x 18

|

|

Rear tyre

|

4.10 x 18

|

|

Weight distribution

|

47/53

|

|

Wheelbase

|

54.5 inches

|

|

Ground clearance

|

7 inches

|

|

Seat height

|

30 inches

|

|

Kerb weight

|

158kg

|

To insure this bike, click here

Bennetts Insurance for your classic bikes

Back in the old days if you wanted the benefits of classic bike insurance, like agreed valuation, events cover and salvage retention, you’d have needed a bike that was 30 years old. Not anymore. Bennetts insurance for classic bikes could offer all these benefits on newer modern classics, as well as vintage models.

Bennetts are a specialist in motorcycle insurance and have been trusted by riders for almost 90 years. We will search our panel of insurers for our best price for the Defaqto 5-star rated cover you need for your classic bike.

Bennetts Insurance for classic bike comes with:

- NO admin fees for additional bike modifications

- Combine your classic and modern bike on one multi-bike policy

Get a competitive insurance quote »

Essential Classic Reading