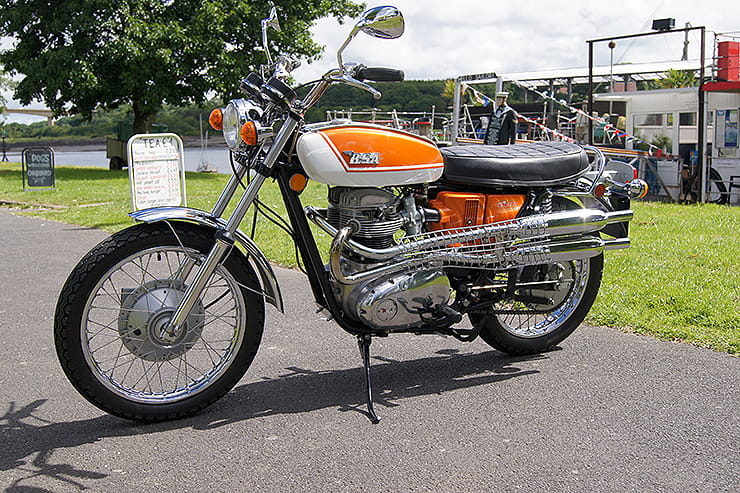

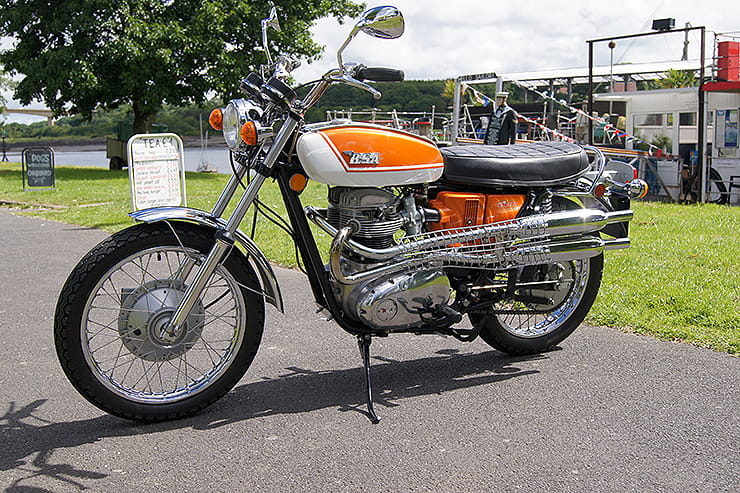

BSA’s biggest marketplace was the USA and Americans loved racing their light, revvy British twins. So BSA took their sensible Lightning 650 and dressed it as a desert racer…

When BSA launched the brave new range to conquer the world back in 1971, motorbicycling folks everywhere stood and stared. This is as it should be. Surely the whole point of a brave new range is that everyone stands, stares and then cries out as one ‘I want that!’ before rushing off to their nearest BSA emporium, slapping down a deposit and tearing pages from calendars, feverishly awaiting the great day of delivery.

Except…

Except it didn’t happen that way. Hardly at all, in fact. You may have heard the stories how ye olde English bike building bosses were, and still are, reviled for being conservative. But that notion is stupidly simplistic. The buying public was conservative too. They bought what they bought. When the old one broke or wore out they wanted another one just like the other one. They all knew what a BSA looked like and their Beezers did not look like these new ones! Add your own expletives. Feel free.

The press hated the brave, new, etc 1971 Beezers. They hated the style. They hated the colours. They hated the old engines, which is understandable, but most of all they hated the height. The all-new, cleverly oil-carrying frame was too darned tall for 1971 motorcycle man. Wow. It was actually a towering 33”. Until you sat on it, at which point it sank by an inch. BSA also painted the new frames grey, which alienated everyone…

The potential punter disliked the very American (read ‘Japanese’) high and wide styling. Slim fuel tanks, slightly forward footrests, wide bars… where would it all end? The sad reality was that old school Beezer buyers wanted the comfortably subdued and trad-styled twins of the 60s. The new kids on the block bought Hondas. The middle ground between them was a sad and lonely place, as can be demonstrated by how few BSA twins built after 1971 are available for sale, and how reasonable are their prices – by classic standards.

The 1971 seat was tall and wide, most riders weren’t

BSA’s 1960s design HQ at Umberslade Hall were only too aware of the oriental invasion. They remembered the great days when one in five bikes on the road was a BSA (really) and they wanted those days back. They decided to replace their range of worthy and only slightly stodgy 500 and 650 twins with a revitalised range of 650s. The 500 were dropped because their brilliant new 350 dohc self-starting twin would fill that gap. Except it didn’t.

There should have been a new big twin engine too. The existing pre-1971 bicycle was pretty competent and the engine needed changing more than the bicycle, but sadly it fell by the wayside and never saw the light of day. Oddly enough, BSA were also hard at work developing a truly unusual and indeed radical machine at the same time: that would eventually appear with Norton badges as the semi-fabulous and famously short-lived rotary series.

BSA’s A65 was developed in the last years of the austere Fifties and the first year of the swingin’ Sixties. In the Great British way, it was a development of the A10 twin which preceded it down the Small Heath assembly tracks. The big engineering push of the day was to combine the engine and gearbox into a single unit. They called this unit construction, with handy logic. In previous decades most engines were built entirely separately from the gearbox, the two being mounted together in steel plates known whimsically as engine plates. This method of construction has several advantages, like you can use the same gearbox with a wide range of engines, which BSA did, However, the supply of Lucas electrical devices, dynamos to power batteries and magnetos to provide sparks, was drying up, so BSA (and most others) switched to more modern alternators for charging and coils for the sparks. Hurrah, etc. And of course a combined engine/gearbox unit is cheaper to manufacture, which helps.

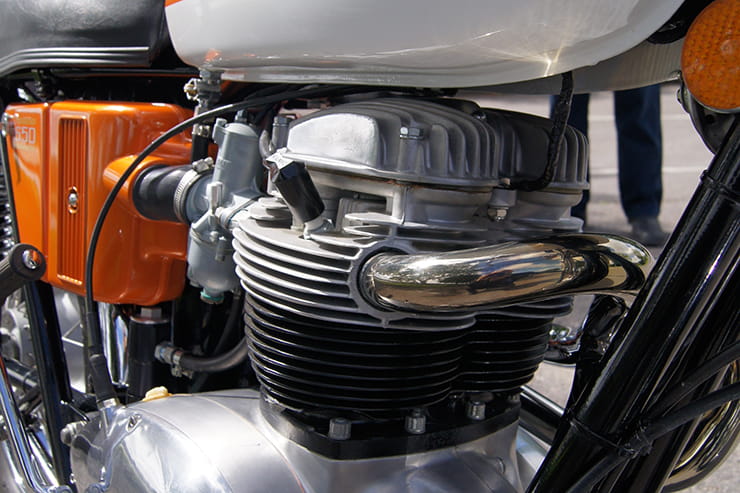

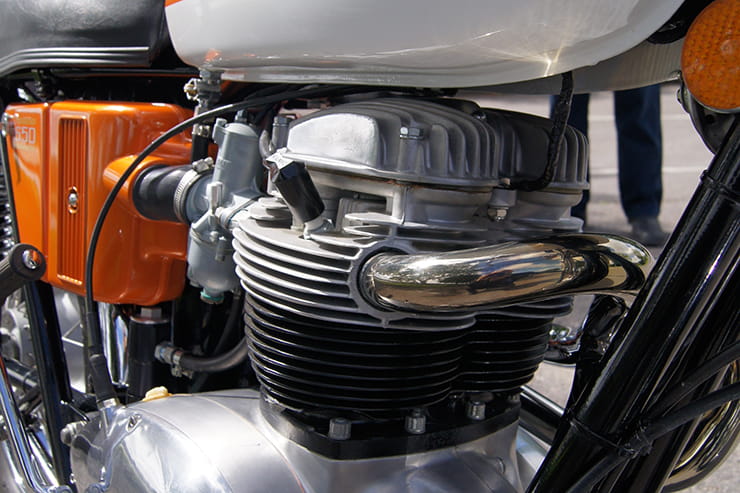

The engine is a simple parallel twin ohv design, with a single gear-driven cam sitting behind the cylinders. It is very conventional.

The frame, however, which spawned the outrage, was very different. For a start its huge top tube contained the engine oil. This was radical in 1971. And all the tubes were welded, not slotted together using forged lugs, which is very 1930s. Add in great narrowness, all-new exhaust and inlet silencing, tricky new brakes and some fairly radical colour schemes (also indicators but no electric foot) and you had an almost modern BSA. Which sounds like a joke, but wasn’t.

Several trims were available, of which the very best (possibly) was the Firebird Scrambler, as seen here. It lasted a whole year. Sometimes you just can’t win…

Not that many were sold so check it’s a genuine Firebird before you buy

Price

Although hardly anyone in the UK bought the delicious Firebirds when they were new, they have grown a lot in popularity since – along with export model BSA Rocket Threes. Prices for the twins remain less scary than for the triples. A good and original Firebird will set you back around £6000, which is a lot more than the £650 or so they cost new. And that’s a private price – expect to be asked up to 50% more for a smart machine in the trade.

It would be cool to reveal at this point that you can pick up a Firebird Scrambler in need of a complete rebuild for sensible money, but you can’t. What you can do, should you decide you want one, is ensure that you’re getting what you think you’re getting. All Firebird Scramblers have an ‘A65FS’ prefix to both engine and frame numbers. The engine number’s on the left side of the crankcase below the cylinder barrel, and the frame is stamped for your delight on the steering stem. Beware fakes, because Noted Experts can always spot them and your resale value will fall if you’ve bought a fake.

Slightly wonderfully, BSA also stamped the little plinth which carries the engine number with a lot of very light ‘BSA’ logos under the engine number. This makes it everso nearly impossible to grind down the number and restamp it.

Happily, it is still possible to find a Firebird privately for around six grand – but a dealer will want more. A lot more…

Feels more powerful than it is because it’s geared for acceleration, not top speed

Power and torque

Despite its musclebound trailbike styling and considerably transatlantic attitude, the Firebird Scrambler is at heart a traditional big Brit twin. You kick it to make it work, and you keep a good eye on its lube levels. You feed it the best fuel you can find, because the stock pistons run a 9.0:1 compression and will pink like a set of shears on crap fuel. If you want to use the performance you’ll need some kind of octane booster. Magic Potions R Us, and so forth.

A claimed 54bhp at a rousing 7250rpm was probably an honest figure…when the engine was new. Torque is quoted at 40ftlb at a startling 6000rpm. I’m sure that’s not right… However, to put this into perspective, 54bhp at 5900rpm is the quoted power output for a 2017 Triumph 900 Street Scrambler.

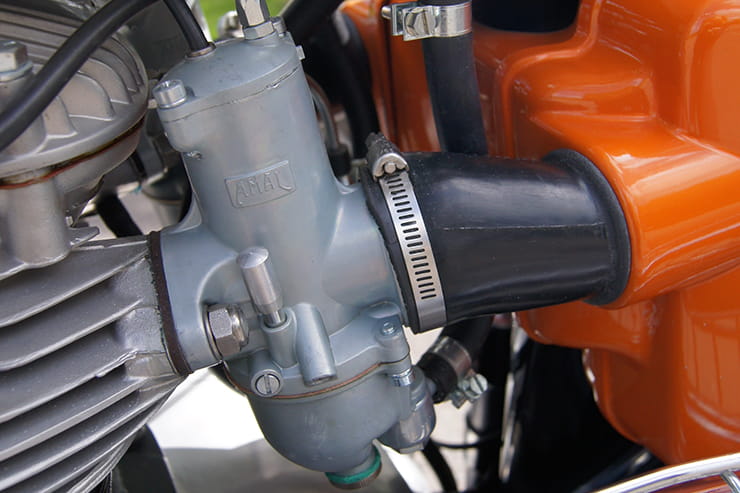

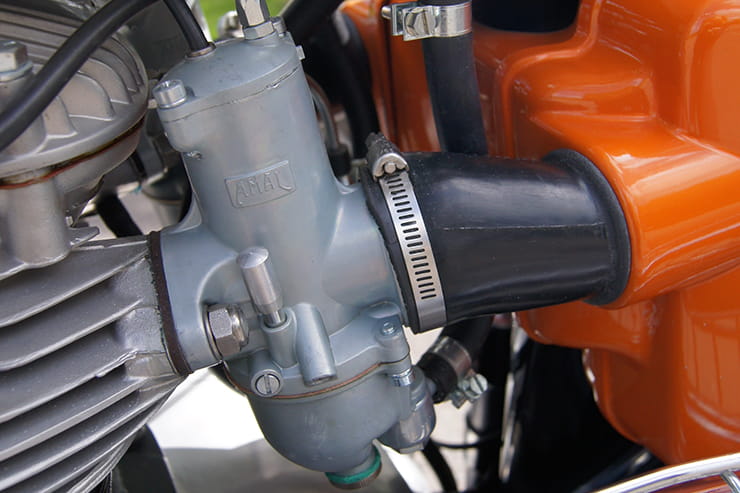

On the road, this translates as something which gets off the line like a Norton Commando, but which revs more easily, not least because it has almost modern almost square internal dimensions of 75x74mm (654cc) and a pair of big gulping 30mm Amal carbs to feed the flames. They’re quick, OK? And they’re under-geared, so meteoric motorway cruisers they’re not.

The little plunger thing is a carb tickler. Like a choke, but much more involving

Engine, gearbox and exhaust

For no reason I’ve ever understood, BSA decided to style their new (for 62) engine to look like an egg. Their previous 650 twin was a mess of fasteners and fittings, and where there’s a fastener there’s a potential stripped classic-fastener and an inevitable oil leak. Oil leaks are unpopular, BSA’s redesign attempted to fix this.

Building the engine and gearbox in a single unit is a smart idea, not least because it does away with all those steel plates, studs, spacers, washers and junk which hold a separate engine and box together. It also does away with the idiotic method of adjusting the primary chain – loosening the gearbox and tilting it backwards to tighten the chain is filthy and tedious. And then you need to adjust the rear chain, fairly obviously. The A65 engine has an almost modern slipper tensioner that’s easy enough to use, though it’s not automatic.

The engine is an air-cooled ohv parallel twin of conventional design. The crankshaft is a meaty affair, with a massive central flywheel between the two big ends and supported by a ball or roller bearing (depending on the year) at the drive end and a beefy phosphor-bronze bush at the timing end. This bush is a famous source of weakness and is mysteriously legendary. The oil pump, a stolid gear device of great reliability, delivers oil under pressure to the bush. This is great: oil and bushes add up to prolonged active life. Oil under pump pressure passes through the main bearing bush into the crank and thus to the shell big ends, which it lubricates. It’s then flung around by the crank’s rotation to lube everything else inside before draining to the bottom of the engine, where it’s scavenged back to the oil tank. There’s a separate feed to the valves.

The legendary weakness is that when the main bearing bush wears, pressure to the big ends falls and they fail. There is of course a fix, most famously the one developed by SRM Engineering.

The crank drives an idler gear which carries the ignition points (one set for each cylinder) and in turn drives the single camshaft which lives behind the cylinders. A nice piece of design involves the cylinder head, which is alloy, unlike the block which is cast iron. The rocker pillars are cast into the head, which means that the handsome rockerbox cover is just a lid, under no pressure and should never leak. Unlike the previous engine’s rockerbox, which was and did.

There’s a Lucas alternator on the drive side of the crank inside the primary chaincases, and the chain is a monster triplex effort which should never stretch, but does. Such is the way with old Brit machinery.

A completely conventional clutch takes drive to the completely conventional 4-speed gearbox and thence to the back wheel.

Most of the A65 twins use an exhaust system familiar to anyone who’s ever seen a 750 Bonneville. Two swoopy chromed headers, joined by a balance pipe in front of the cylinder head, flow the gas to a pair of megaphone-pattern – but rather subdued – silencers. The Firebird Scrambler however, boasts the tangled arrangement you can see in the pics and is rather more vocal. It should be all-black, but many owners prefer chrome.

Frame is heavy (more so when full of oil), but very tough

Handling, suspension, chassis and weight

BSA’s plan to usher in the Seventies with world-class bikes involved a pair of new frames; one for the singles and the other for the twins. They were completely different, but similar in that they contained the engine’s oil, removing the need for a separate tank. In the case of the BSA twin frame seen here, which incidentally continued in slightly modified form wrapped around all Triumph’s big twins until the 750 Bonneville, the oil is held inside a seriously hefty 2.7” tube which runs from the steering head to the nose of the seat, whereupon it dives south to below the swinging arm pivot, ending in a blanking plate with a rudimentary gauze strainer built in. It’s big, and holds 5 pints of oil. It’s also enormously strong, and is the key to the bike’s excellent handling.

The engine is held by a pair of tubes running down from the steering head, under the engine, where they’re welded to the big top tube, then loop back up to the rear suspension pick-up points. It’s a great frame, really, and is capable of surviving serious damage. The oil filler is beneath the nose of the seat, and the drain is in the plate at the bottom of the big tube.

Front forks are the handsome slimline variety fitted to almost all BSA and Triumph machines from the 1971 season until the end of T140 Bonneville production. They’re good forks and work well with a steady predictability if you press on – which you surely will if you want to get the best out of a Firebird. There were a few upgrades to the same fork when used on the T140 twins so if you want to upgrade a little you can. You can also fit progressive springs and fiddle with the dampers should you wish, but the factory offered no adjustments at all at the front, and only preload at the rear, so if you enjoy a decent fiddle, feel free to spend more money.

Original rear shocks will all be worn out by now, and lots of aftermarket replacements are available. Some of them very cheap and some of them very good.

The Firebird weighs in at a reasonable 395lbs (180kg), and the frame handles this with ease. The front rim is 19-inch, with a 3.50 section tyre, while the 18-inch rear takes a 4.00 gripper. The steering is a curious mix of agility and stability, which is all part of the charm - one of many reasons for riding a bike like this.

Handling and steering are excellent. Really. No reservations. If you want to exploit the fine roadholding, and modern rubberware encourages this, you’ll need better ground clearance, which means ditching the centrestand and letting the factory-fit folding rests do their stuff if you get exuberant. BSA intended their Firebird Scrambler to be export-only, and built it to handle the US passion for desert racing, boonie-bashing. It actually does this. Did anyone mention braking?

Some of them work, some of them don’t. No one knows why.

Brakes

It is always reassuring if your bikes brakes a) work, and b) work predictably. For the great 1971 leap-forward, BSA ditched the excellent anchors fitted to the 1970 models and replaced them with a set of drum stoppers which were intended to work in most models in both BSA and Triumph ranges. They look great, with silver finished and notably conical hubs containing the working bits. The rear one is a rod-operated sls device which works well. No more need be said.

The front brake is a clever piece of engineering, which uses car-type Micram shoe adjusters, accessible through a hole in the hub for a gentle screwdriver tweak when required. Unlike previous Brit 2ls systems, the operating arms for each shoe were pulled towards each other rather than operating in parallel: the inner cable pulls the front lever towards the rider, while the outer cable acts equally and oppositely, pushing the rear lever towards the front. It’s clever and sometimes it works very well indeed.

And sometimes… it doesn’t work at all. This appears to be down to magic. Ride the bike before you buy it. Check that the brakes work. If not, walk away.

Narrow tank plus wide seat equals knees in the breeze

Comfort

BSA seats are great for a hundred miles – more if you are internally padded, less if you’re not. They’re also quite wide at the front, which spreads your legs apart, which means that your knees will be untroubled by contact with the petrol tank. This is great if you like your knees in the breeze; less so if you prefer to grip the tank to aid your exciting riding style.

Firebirds have great wide US bars. They’re actually very comfortable, and if you can find a genuine set or a very close repro bend, then you’ll appreciate why BSA put the footrests where they did. Riders of UK market oily-frame Beezers get backache because the low Brit bars bend the back. This is not a concern with the Firebird. It sits you up in space, leaving you loads of leverage to indulge your desert racer fantasies.

Vibration is an issue. Things will fall off and things will break. If they don’t, you’re a sensible and considerate rider.

Use all the revs and you’ll be wishing your fillings were rubber-mounted too

Equipment

You’ve got a powertrain! You’ve got a bicycle! You’ve got great looks! What more could you ask for? You get twin clocks, three idiot lights, and indicators. The latter can be great fun, as the healthy vibes cause them to rotate, providing hours of fun in the darkness.

Because this machine was intended to be used off-road, BSA fitted it with folding footrests – if it’s not got these, consider the bike’s authenticity.

1971 BSA A65FS Firebird Scrambler Verdict

These are great bikes for anyone who wants a classic ride which will go like stink, handle brilliantly, make fabbo noises and turn heads wherever it’s parked. Subtle they’re not. Especially in their natural orange.

Of all the very many BSA twins, this is the one which turns the heads as it grumbles through the traffic or snarls along a twisty road. The Firebird is comfortable, quick and decently rapid. Two things let it down. Three, if you count the very variable front brake. First: there’s no electric start. This is a high-compression (9.0:1) engine, first gear is fairly high, which means that it demands a decent boot application to stir it into life. Modern ignition systems help, as do carbs set up to run on modern combustibles. Second: there’s no top gear – no fifth in the 4-speed box. With the Firebird’s overall gearing it accelerates like a rocket, but 70+ cruising is not for anyone with a bad dose of mechanical sympathy. Top speed is over the ton, but you’d need to be seriously rich or uncaring to do that very often.

They’re some kind of ultimate: the ultimate 650 Beezer. And… they are enormous entertainment.

Three things I loved about the BSA A65FS Firebird Scrambler

• Excellent performance

• Outstanding looks

• Superb handling

Three things that I didn’t…

• Variable braking

• Vibration

• Kickstarting

1971BSA A65FS Firebird Scrambler spec

|

New price

|

£650 in 1971

|

|

Current value

|

£9000

|

|

Capacity

|

654cc

|

|

Bore x Stroke

|

75 x 74mm

|

|

Engine layout

|

OHV parallel twin

|

|

Engine details

|

Overhead valves, two per cylinder. Single gear-driven camshaft

|

|

Power

|

54bhp @ 7250rpm

|

|

Top speed

|

105mph

|

|

Transmission

|

4-speed, chain drive

|

|

Average fuel consumption

|

45mpg

|

|

Tank size

|

2.5 gallons

|

|

Frame

|

Steel tube cradle

|

|

Front suspension

|

BSA 35mm forks

|

|

Front suspension adjustment

|

N/A

|

|

Rear suspension

|

Girling rear units, tubular steel swinging arm

|

|

Rear suspension adjustment

|

Spring preload

|

|

Front brake

|

8-inch 2ls drum

|

|

Rear brake

|

7-inch sls drum

|

|

Front tyre

|

3.50 x 19

|

|

Rear tyre

|

4.00 x 18

|

|

Wheelbase

|

57”

|

|

Ground clearance

|

7”

|

|

Seat height

|

33”

|

|

Kerb weight

|

420lb

|

Looking for motorbike insurance? Get a quote for this bike with Bennetts motorcycle insurance