Triumph’s Bonneville is one of the most long-lived motorcycles ever, and falls into two camps; ancient, built in Meriden, and modern, built in Hinckley. In between came the Harris Bonneville, built in Newton Abbott.

Left side gear lever makes all the 750 Bonnies easier to ride as a first classic for modern riders

There’s an oft-quoted notion that the last model in a long line is the best of the bunch. If that’s the case, then the handsome Bonneville standing proud before you is the best of the first – if only because it’s the last. The last of the ohv air-coolers at any rate. But… is it actually any good? How does it compare with the last of the Bonnies built by Triumph Engineering, late of Meriden? Because this machine, and a few hundred others like it, was built in Devon by LF Harris Ltd, noted suppliers of Bonneville spares.

Picture the scene. Your name is John Bloor and you’ve just bought the entire everything to do with Triumph, probably the most successful British bike builders of all time. You’ve made the 100% intelligent decision to have nothing to do with the leaky, rattly, slow, unreliable heritage, and intend instead to design an entirely new range of Triumph motorcycles from scratch. Which takes longer to do than it does to say out loud, even if you say it very slowly.

This means that there’ll be a big gap in production, and the name ‘Triumph’ will fall gracefully from the collective motorcycle consciousness, unless … unless you allow LF Harris to build old-style Bonnies until you’re ready to spring the new multi-pot machines upon a trembling world. It made sense then and it makes sense now. So that’s what JB did.

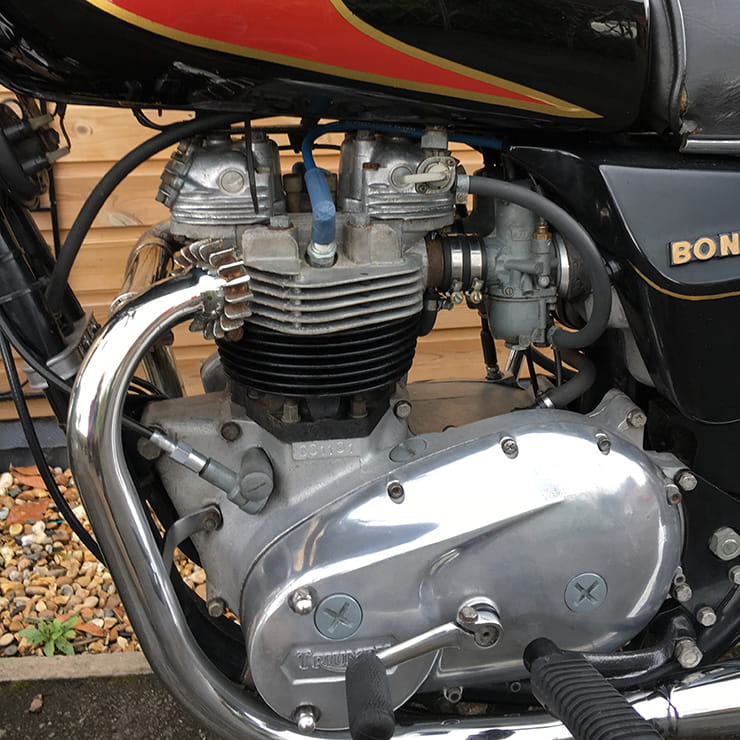

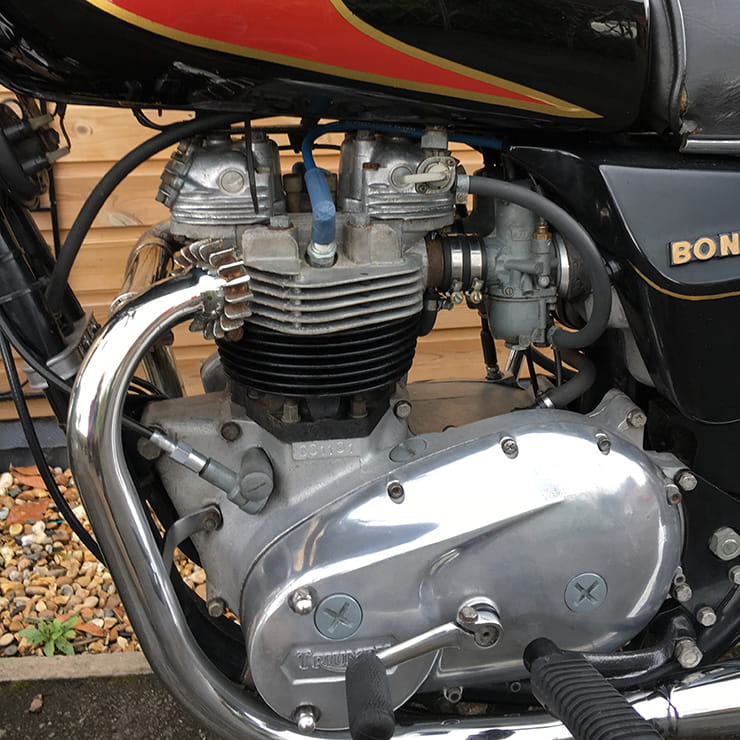

Harris opened an assembly facility in Newton Abbott, Devon, and announced their intentions to a delighted trad-Brit two-wheeled world. Expressions of adoration poured in, everyone guaranteed to buy one, so LFH went to work. They weren’t allowed – for a reason which never made any sense – to use the last best designs from Meriden, so no electric hoof and no TSS-style bottom end, and some of the tooling was so utterly worn out that it was unusable.

‘Hipster look’ tank filler and paint job at least 25 years before ‘hipster’ was a thing

So LFH went to Europe, chequebook in hand, and bought a pile of Paioli forks and rear shocks, as well as Radaelli rims, Magura switchgear and master cylinders, not to mention rather useful Brembo brake calipers. These do – you’ll be unsurprised to learn – change the machine’s character quite a bit. And you will have observed that the silencers are also Italian – Lafranconi – and not only look OK and work well, but sweep up more than the earlier devices, thus allowing more ground clearance because the centrestand can rest higher. This is good, because the bike is a true fling-around machine. Really.

Another mod over the last of the Meriden twins was a peculiar Amal Concentric carb, replacing the unlovely Mk2 devices fitted to the last of the Meriden machines to meet US emissions legislation. Dubbed the ‘Mk1½’, they proved decently useful. And remain so.

Does it work as a Bonnie? Is it the best of the Meriden machines? Yes and … possibly.

Harris built around 1250 of his Bonnies before startling the world by ending production and introducing his new Matchless G80. We all make mistakes…

That’s a fine looking rideable classic with zero depreciation for less than the price of a new commuter

1988 Triumph T140 Bonneville Prices

This is that Piece of String question. Pricing a T140 Bonnie – any version – is more down to the popularity of the model (or otherwise) and the great condition (or…) than anything else. Harris machines fall into the higher price range, but are more dependant than most models on condition. Two reasons: when new they were usually bought by riders rather than keen Meriden Triumph worshippers (as they weren’t built in Meriden), and build quality can be somewhat variable. Bad suggestions were made that the bikes used components left over from the Meriden collapse, and certainly the engines varied between smooth and quiet and rough and rattly. We’ve ridden several examples of them both – and you won’t know into which category a bike you’re considering falls without riding it. Remember this, auction fans!

Current dealer pricing puts them around £4000, as do auction sales. You might pay less privately, or you might not. Sweetest of them is the carb Tiger 750, but they’re very rare, so you pay more for the pleasure of having but a single Amal…

Fifty optimistic horses ready to lollop, if not exactly gallop

Power and torque

This is a T140 Bonneville. So expect around 50bhp, delivered at around 6800rpm. If you’re unfamiliar with Triumph’s air-cooled pushrod twins you will be terrified by the insane cacophony which arrives with peak power at peak revs. Work an old engine that hard and you’ll soon learn to make friends with one of the several Triumph twin specialists – a built-in social life. The nicest people may ride Hondas, but the mechanically competent can handle a Triumph.

But that’s only a tiny part of the big Triumph twin experience. The bikes did not stay in production for almost exactly a decade because they explode every ten miles, not because they are nasty thrashy devices. Ridden at – shall we say – main road speeds they are excellent. Power comes in easily and almost in parallel with an always impressive wave of grunt. It’s perfectly possibly – and indeed comfortable – to accelerate hard from below 2000rpm, riding a wave of torque which carries you easily into power delivery land, which begins in earnest around 4000rpm.

As the torque plateaus and power builds, the engine is working harder and its elderly long-stroke dimensions (a rousing 76 x 82mm) produce high piston speeds which in turn mean that the rider becomes very familiar with the joys of parallel twin vibes. Nothing unpleasant below 5500rpm, but much over that things do sound mechanically exciting.

Slightly marvellously, the five ratios in the box and the gentle overall gearing match perfectly with the engine’s strong spots, resulting in a true bike for all reasons. It’ll chug through traffic at 35 in top, or 4th or 3rd… And will fling heroically around the back wheel on any decently fast road with decent bends – all of this based upon the engine’s comfortable torque and power developments. There may not be a huge amount of either, but the manner of delivery encourages many ways of making progress, from sedate 50mph top gear ambling to dual carriageway 75mph cruising – even a little 80mph nutcase stuff.

Single carb, kickstart-only starting, points ignition and the oil is in the frame. Charming and thankfully, it works

Engine, gearbox and exhaust

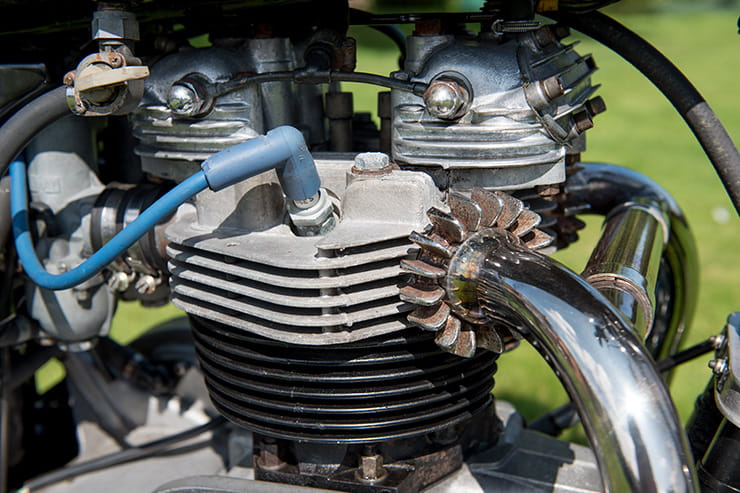

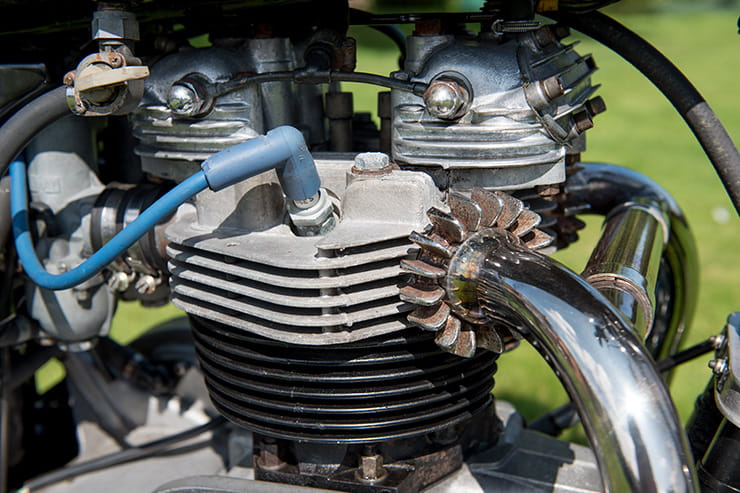

The 750 Bonneville engine is as basic as they come. The original parallel twin design came out in the late 1930s, and designer Edward Turner’s intention was to produce a twin cylinder device which would fit into the bicycles of the then dominant single cylinder machines without looking outrageous, clumsy, bulky or technically threatening. He succeeded, as you already know. The original 500cc twins were almost as compact as a 500 ohv single to look at, but their manner of going was rather more exciting.

By the time the 750 Bonnies appeared in 1973, the gearbox was built into the crankcase casting, sparks came from coils rather than from a magneto, and electrical sundries were driven by a simple 12V alternator rather than a tiresomely complicated 6V dynamo. The basic engine had not changed much, although it had been developed a lot.

The heart of the machine is a simple and strong crankshaft carrying a big end each side of a central flywheel. No centre main bearings here: the crank is supported at each end by hefty ball and roller bearings, which keep everything commendably slim and simple, but the 360° layout and lack of balancing in the modern sense allows the movement which produces the famous vibration. That would be both hefty pistons whamming up and down together, balanced only by the equally hefty flywheel. Sounds scary – works surprisingly well, which is why they sold so well.

Two camshafts operate the overhead valves – two to each cylinder – and are mounted each side of the crankshaft and parallel to it, driven by gear from an idler gear between camshaft pinions and the crank itself. An extension of the exhaust camshaft carries the points for the coil ignition system, while the inlet camshaft drives the oil pump.

The oil pump itself is a thing of mystery and wonder to modern eyes. A peg on the inlet camwheel locates in an alloy block which slides back and forth as the wheel rotates, converting round-and-round movement into up-and-down, so operating the pump, which is a pair of plungers running side by side in a common casting bolted to the crankcase. The smaller diameter plunger supplies oil under pressure to the big ends, which the larger plunger returns it to the oil tank – which in this case is the bike’s frame.

Some are smooth and lovely, others rough and vibey. A test ride tells all, buying without one is risky

Each camshaft drives a pair of pushrods – themselves contained in a pair of gloriously archaic chromed steel tubes mounted outside of the cast-iron barrel and sandwiched between the cylinder head and crankcase – which operate the valves. Lots of opportunities for the famous Triumph leaks here: the pushrod tubes offer a tantalising array of solutions to sealing their various joints, while the rocker boxes are separate castings to the cylinder head, with all the potential for merry leaking between the joints. This is of course all part of the considerable charm. Or not.

It’s also worth remembering that many later Meriden twins were fitted with an electric start, but that no Harris models were – officially. You can retro-fit the kit for the electric foot, but it’ll set you back around £2000.

Drive is taken from the left-side end of the crankshaft (which also carries the rotor for the 12V alternator) via a seriously beefy triplex primary chain to a conventional

multiplate clutch which drives a conventional 5-speed gearbox. Few problems here, so long as lube supply and quality are maintained. And the clutch should be nice and light and progressive, too. If it’s snatchy, grabby or slippy – or heavy – then there’s something wrong with it.

Triumph twin exhausts are simple things. The single exhaust valve in each cylinder vents into a single pipe, which in turn puffs wearily through silencers which grew bigger with ever-tightening noise regulations through the 1970s. By the time the Harris Bonnie – as seen here – appeared, Triumph ditched their own silencers and bought them in from Lafranconi. A good move, as they look good, sound good and work good.

There are very many aftermarket alternatives. Lots claim performance increases but many are just louder, mostly.

Aftermarket oil cooler is a popular modification

Handling, suspension, chassis and weight

The final major development of Triumph’s venerable bicycle came in 1971, when the glory that was BSA / Triumph Group introduced an entirely new frame. This was notable for two features: firstly it contained the engine’s oil in a large diameter tube running from the steering head, all the way down to the swinging arm pivot and beyond; secondly it was too tall. And the Triumph engine didn’t fit it at first, which must have been amusing.

The engine is carried in a duplex cradle running from the steering head, under the powertrain, before looping back up to the rear suspension top mounts. The swinging arm is a simple tubular effort mounted in the big oil-bearing member and controlled in its exciting up and down movement by a pair of telescopic shocks. These were typically Girling springers on most earlier bikes but the Harris machine used Paioli shocks – which are very effective, in fact, and easily up to handling the Triumph’s 410lbs (180kg or so, depending on the weather) and probably that of an average rider too. The stock Paiolis can get a little tired if expected to support a hefty rider, pillion and luggage, but if you’re into heavyweight touring there are plenty of aftermarket alternatives available.

Forks, brakes, shock absorbers and silencers were Italian-sourced and none the worse for it

The front wheel is carried by another set of Paioli components; an entirely conventional set of 38mm telescopic front forks fitted neatly into Triumph yokes and – whisper this – working rather more effectively and indeed comfortably than the elderly British originals. It may not be fashionable to say it, but the 1980s Italian suspension works rather better than the 1970s British originals – as you might expect, although it’s not a popular opinion. Trust us: we’ve ridden lots of these Triumphs.

Although the chassis package is basic twin-shock stuff, with nothing even faintly adventurous in design or execution, it works remarkably well. There was a reason the T140 Bonneville was MCN’s Machine Of The Year, and riding one as it was intended to be ridden will soon remind you of the fact.

If any oily-frame Triumph fails to handle and steer very well indeed, then there’s something wrong with it. In the case of the Harris Bonnie we’re looking at here, check that the suspension isn’t entirely worn out or bent, because it may well prove difficult to find new original components. Replacements – as for everything Triumph – are of course available.

1988 Triumph T140 Bonneville Brakes

One of the best features of the 1985-88 Harris Triumphs is the braking. The earlier Meriden single-disc set-up works well enough by the standards of the mid-1970s, but the set of twin Brembo callipers gripping the twin front 260mm rotors are a serious improvement on the Meriden equivalent. There’s another single disc at the back, which is fine if unremarkable, as rear brakes should be.

And if the Brembos don’t fulfil your need to perform radical stoppies on your elderly ohv Brit twin, then there are several upgrades available. At a cost…

Two different styles of fuel tank. This is the smaller ‘export’ model

Comfort

Harris Bonnies came in two basic versions; home and export. The export machines use a smaller fuel tank and sometimes but not always higher bars too. If you have any pretensions at all to really rapid riding, the lower bars are less uncomfortable at, say, 70+mph, otherwise the higher bars and small tank provide good comfort and levels of low speed control, as well as that Officer And A Gentleman nostalgia burst.

Footrests will feel too far forward to anyone more familiar with modern machinery, but moving them rearward is not difficult, and several aftermarket options are available. As are more modern seats, although there’s nothing wrong with the originals as far as depth of padding and a grippy surface are concerned.

They’re rubber-mounted for a reason – some are more vibey than others

Equipment

As basic as it is traditional. Speedo and tacho (from a couple of different suppliers, sometimes not matched – just to give concours terrorists the vapours) and a small collection of idiot lights. Early Harris machines used Lucas switchgear, then swiftly shifted to Magura kit, which works well enough. You get indicators, too, but that’s about as modern as it gets.

1988 Triumph T140 Bonneville Verdict

As a solid, reliable, entirely competent introduction to the world of active old Brit bike riding – rather than simply owning – the last of the ohv Bonnies comes highly recommended. Its performance is modern-road competent, its steering and handling are excellent, it has bright lights, great style and limitless opportunities for enthusiasm. The ownership experience should be excellent – so long as you’re not expecting Hinckley Triumph or Kawasaki retro twin modernity or sophistication.

There’s a reason Triumph twins sold so very well for so very long, and it’s all to do which how easy they are to live with, to ride, to maintain and to simply enjoy. They sound great too.

And an unappreciated benefit is that if you’re careful when you choose your own, but decide that the Triumph way is not your way, you shouldn’t lose money when you sell it again.

Aftermarket shocks are common and modern tyres are a big improvement

Three things I loved about the Harris Triumph

• Entertaining mid-range

• Classic sound effects

• Excellent handling

Three things that I didn’t…

• Variable component quality

• Lack of electric start

• Poor motorway abilities

1988 Harris Triumph Bonneville specs

|

New price

|

£2760 in 1986

|

|

Current value

|

£4000+

|

|

Capacity

|

744cc

|

|

Bore x Stroke

|

76 x 82mm

|

|

Engine layout

|

OHV parallel twin

|

|

Engine details

|

Overhead valves, two per cylinder. Twin gear-driven camshafts

|

|

Power

|

c50bhp @ 6500rpm

|

|

Top speed

|

105mph

|

|

Transmission

|

5-speed, chain drive

|

|

Average fuel consumption

|

45mpg

|

|

Tank size

|

3 gallons

|

|

Frame

|

Full duplex steel cradle, oil-bearing

|

|

Front suspension

|

Paioli 38mm front forks

|

|

Front suspension adjustment

|

N/A

|

|

Rear suspension

|

Paioli rear units, tubular steel swinging arm

|

|

Rear suspension adjustment

|

Spring preload

|

|

Front brake

|

Twin 260mm Brembo, 2-piston calipers

|

|

Rear brake

|

260mm Brembo disc

|

|

Front tyre

|

100/90 H19

|

|

Rear tyre

|

110/90 H18

|

|

Rake/Trail

|

4.9 inches

|

|

Dimensions

|

87.5” x 29” x 131”

|

|

Wheelbase

|

56”

|

|

Ground clearance

|

7”

|

|

Seat height

|

31”

|

|

Kerb weight

|

420lb

|

Bennetts Insurance for your classic bikes

Back in the old days if you wanted the benefits of classic bike insurance, like agreed valuation, events cover and salvage retention, you’d have needed a bike that was 30 years old. Not anymore. Bennetts insurance for classic bikes could offer all these benefits on newer modern classics, as well as vintage models.

Bennetts are a specialist in motorcycle insurance and have been trusted by riders for almost 90 years. We will search our panel of insurers for our best price for the Defaqto 5-star rated cover you need for your classic bike.

Bennetts Insurance for classic bike comes with:

- NO admin fees for additional bike modifications

- Combine your classic and modern bike on one multi-bike policy

Get a competitive insurance quote »