Styled like an R1 with even more aggression. Sadly the bite didn’t match the bark

Defining what makes a bike ‘classic’ is tricky. Sometimes its because we all bought one (Yamaha RD350LC), other times it’s because no one did (Ducati MHR1000). Successful race winners like Honda’s RC30 see their prices go stratospheric, while the ultra-exotic bike that was equally successful (Ducati 916) sees prices nudge up gently.

And then there are the turkeys. Suzuki’s horrible TL1000S is seen as some kind of macho ‘widow-maker’ man’s bike, while Honda’s VTR1000 Firestorm, which was almost as wayward down a bumpy road is now just a cheap hack. A Honda RC45 that devoured millions of HRC Yen and won a single world title and pretty-much nothing else outside of the Isle of Man will cost you four times as much as the Ducatis that humiliated them.

But one bike stands above all the others when it comes to being an utter racing flop that somehow commands the craziest of price tags. Say hello (because we know you’d all forgotten about it) to Yamaha’s original 1999 YZF-R7.

For and against

- Built like a factory racer

- Steering and suspension that still feels very special

- You’re unlikely to see another one

- Slower than a ten year old sports 600

- Reputation for unreliability

- Both the above mean that you’ll never ride it

Styled like an R1 with even more aggression. Sadly the bite didn’t match the bark

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Price

Expect to pay at least £25k for an R7. And don’t take too long making your mind up because, bizarrely, they sell fast thanks to fading mid-life memories of Nori Haga being the man that almost won the 2000 WSB title by riding one sideways until he was docked points for a minor indiscretion with some ‘cough-syrup’.

Only 500 YZF-R7s were ever built (the minimum requirement for superbike racing). Nitro Nori personally destroyed a large percentage of them and many others were thrown in a metaphorical skip by race teams frustrated with their lack of competitiveness and unreliability. So there aren’t too many left.

The list price in 1999 was £22k and priority went to race teams, not road riders. A brand new YZF-R1 could be bought in dealers for around £8000, made 40 per cent more power, weighed roughly the same and was about 1000 times more reliable.

Perhaps even more relevant was the awesome new YZF-R6 that Yamaha also launched in 1999. That bike made pretty much the same horsepower as a stock R7 and cost a third of the price.

It soon became clear that the R7 wasn’t an easy bike for privateer teams to run competitively and demand slowed rapidly meaning many of the original 500 remained unsold. These tend to be the ones that come up for sale (because most of the race bikes either destroyed themselves or were smashed to pieces by their riders chasing down a Ducati). Until recently it wasn’t unusual for brand new R7s originally sent to far-flung countries to turn up in their crates and be offered for sale.

Given the lack of racing success and their reputation for unreliability you’d expect an R7 to be in the same price bracket as Kawasaki’s ZXR750K or ZX-7RR. Or Maybe Bimota’s even more rare SB8K. Sadly, you’d be wrong. I can’t remember the last time I saw an R7 advertised for less than £25k, the cheapest on sale as I write this (June 2021) is £35k and even at those prices they sell fast.

And that is the mystery of classic bike pricing in one simple example. Go figure…

98bhp at the back wheel was the same as a £7000 sports 600 in 1999

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Power and torque

Because they were only making 500 bikes, Yamaha built the roadgoing R7 in one-spec only to satisfy all the different markets. This meant restricting it to the power output of the grumpiest country, which, in 1999 was Germany at 100bhp. So, in standard trim an R7 makes around 96bhp at the back wheel, which is almost 20bhp less than its predecessor, the FZR750R OW01 made ten years previously.

Some of the restriction was simple – the standard throttle cable only allowed 75 per cent of available travel. But much of it – switching on the secondary fuel injectors – for example, required the £10k race kit and losing your lights, indicators and horn. It didn’t take long before clever engineers worked out how to fit most of the race kit and still have the lights, which liberated around 30bhp more. But your mate’s bog standard YZF-R1 would still have left it for dead, if only because it made 20 per cent more torque.

Superbike rules in 1999 allowed four cylinders and 750cc or two cylinders and 1000cc. Ducati’s big twins won all-but two WSB championships between 1990 and 1999 despite Honda spending more on their RVF750 RC45 than pretty much the rest of the field combined. The only way for a 750 to compete with the Ducatis was with enough revs to make crazy horsepower. Power comes from torque multiplied by revs and the R7 made the same torque as a sports 600. Sports 600s made 100bhp at around 11,500rpm and so, to reach 150bhp with the same torque the R7 needed an awful lot more revs. Which is exactly what the race kit provided.

Unlike the R1 the gear linkage doesn’t run through the frame

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Engine, gearbox and exhaust

State of the art in 1999 with only superficial regard for roadgoing longevity. To make the power it had to rev and to reach those revs everything had to be as light and slippery as possible. So tolerances were tight, Titanium was everywhere and reliability was determined by a typical WSB race weekend involving about six hours of flat-out running.

Five Titanium valves per cylinder were 48% lighter and stronger than those on the YZF750 but the advantage of five-valve design had vanished by the mid-90s as four-valve evolution gave greater valve area and gas flow with less complexity.

The R7’s one-piece crankcase/cylinder design had been seen in Honda’s FireBlades and CBR600s for almost a decade but was new to Yamaha. Forged pistons and H-section Titanium conrods were standard racing fodder.

Fuel injection was relatively new to Yamaha in 1999. Switching off the secondary injectors might have made sense as a restriction method, but in reality it was the big mistake that prevented the R7 ever becoming a legend on the road – especially when the other restriction, the too-short throttle cable was a work of genius as the world’s simplest-ever mechanical restrictor.

The gearbox was stacked behind the cylinders like the R1 and R6 which kept the engine very compact and allowed the chassis to run both a short-ish wheelbase (surprisingly not as short as the roadgoing YZF-R1) for quick steering and long swing-arm for stability.

Not a choke lever, but a fast-idle setting for the fuel injection

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Reliability

Sadly, all this high-tech was wasted because the design of the bottom-end of the engine was flawed. Like all legendary failures, there’s more than one theory. Some said the oil pump flowed too fast leading to cavitation in the oil and poor lubrication. Others said it was oil starvation and the crank needing opening up to allow more flow. Others reckoned it was the big-end design that was flawed and using the bearing shells from a Kawasaki ZX-9R cured the problem, while yet more said it was the design of the crank, with weight in the wrong areas, making it ‘whip’ and, also that the H-section con-rods would twist. So, depending on your expert you either need to reduce the oil flow to the bottom-end or increase it, or have a new crankshaft made to the spec that the Factory finally fitted in 2000. Good luck making your decision.

And, of course, the problem with it being a limited-edition racing special is that your local Yamaha dealer would have struggled to get spares when it was new. 22 years later you’re in the fascinating world of forum experts, a handful of specialists and making friends with dealers who know and understand the difference.

The only time I’ve been lucky enough to ride an R7 was when a friend of the magazine I worked on at the time offered to lend us his bike. He often lent us stuff but this was the only time it came with a list of do’s and don’t’s and a limit of just 90 miles. Which says more than words ever can.

Frame, swing-arm and suspension were a long way ahead of a standard road bike

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Handling, suspension, chassis and weight

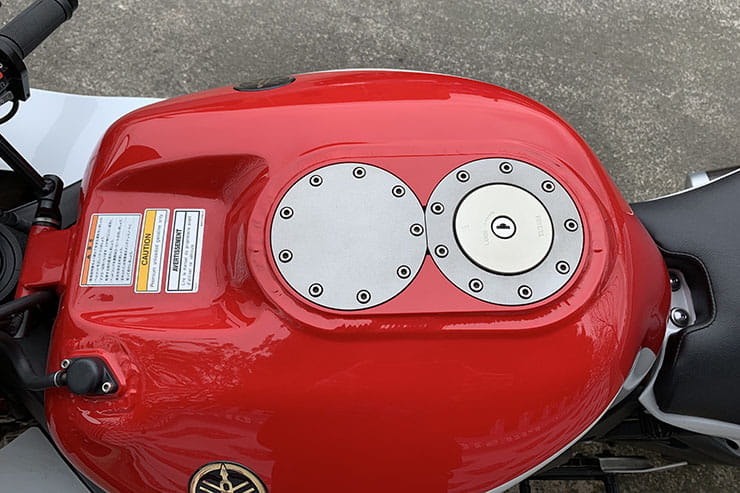

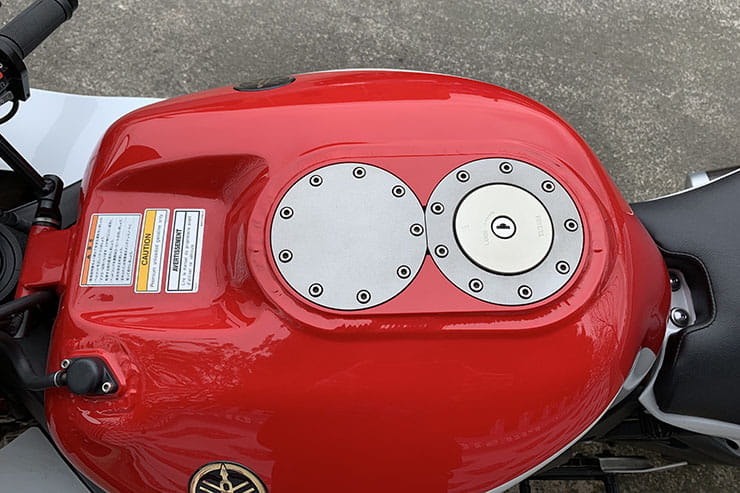

Yamaha made a lot of the similarities between the R7’s chassis and that of their YZR500 GP bike of the time. The wheelbase was 20mm longer than an R1 or R6, but adjustable swing-arm pivot and fork offset allows a huge amount of fine tuning to handle as well at Thruxton as it does at Cadwell Park. The welds on the chassis (and the 24 litre fuel tank) look like a proper factory race bike and the frame is a lot stiffer than the roadgoing YZF-R1. The suspension is state-of-the-art (in 1999) Ohlins and on the road you get quick steering, stability at speed, a plush ride and immaculate roadholding on bumpy B-roads. The reality is that there are so few moments when you can really commit to a corner on the road that you’ll only glimpse what the R7 chassis is capable of once or twice each ride. But when you do, you’ll understand. Whatever the problems with the R7’s engine, the chassis and suspension is still almost flawless

Brakes were good in 1999 but haven’t aged well. Racers swapped them for proper race kit asap

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 Brakes

Yamaha’s blue-spot Sumitomo calipers were as good as Japanese braking got in 1999. Back then you’d rarely see Brembo kit on anything Japanese and the standard units were more than enough for the performance on offer. Fast forward to 2021 and brakes are one of the things that have improved the most on modern bikes. The R7’s standard units date it faster than anything else. The good news is that all service parts for the brakes are still available because so many other bikes used them.

All you need to go racing…plus a clock and a steering lock to prevent it getting nicked at the chippy

Rider aids and extra equipment / accessories

Nothing. No ride-by-wire throttles, no ABS or traction control. No wheelie control or riding modes either. Back in 1999 the fuel-injection with dual injectors was as complex as motorcycling got. There’s what looks like a choke fitted in the lhs of the fairing. It’s a ‘fast-idle’ lever, which was a feature of early fuel injection systems.

Build quality is like you’d expect on a factory racer

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 verdict

In a world where 100bhp is an insult to an adventure bike the R7’s restriction is its biggest problem. Not just because of the actual numbers, but without the secondary fuel injectors working it revs surprisingly slowly and feels lethargic. There’s no rush of power like the Kawasaki WSB specials with flat-slide carbs. You can never commit fully enough on the road to enjoy the chassis and you can’t go fast enough on track to enjoy it either.

1999 Yamaha YZF-R7 spec

|

New price

|

£21,749 (1999), £25k+ now

|

|

Capacity

|

749cc

|

|

Bore x Stroke

|

72mm x 46mm

|

|

Engine layout

|

Inline four cylinder

|

|

Engine details

|

Water-cooled, 20v, DOHC

|

|

Power

|

98bhp (78Kw) @ 11,500rpm

|

|

Torque

|

47 lb-ft (76Nm) @ 8750rpm

|

|

Top speed

|

160mph

|

|

Transmission

|

6- speed, chain final drive

|

|

Average fuel consumption

|

45mpg

|

|

Tank size

|

24litres

|

|

Max range to empty (theoretical)

|

230miles

|

|

Reserve capacity

|

45miles

|

|

Rider aids

|

none

|

|

Frame

|

Alloy deltabox

|

|

Front suspension

|

43mm USD forks

|

|

Front suspension adjustment

|

Preload, rebound, compression

|

|

Rear suspension

|

Single shock absorber

|

|

Rear suspension adjustment

|

Preload, rebound compression

|

|

Front brake

|

Twin 320mm disc, 4-piston calipers

|

|

Rear brake

|

245mm disc, 2-piston caliper

|

|

Front tyre

|

120/70/ZR17

|

|

Rear tyre

|

180/55/ZR17

|

|

Rake/Trail (stock setting)

|

22.8°/95mm

|

|

Dimensions

|

2060mm x 720mm (LxW)

|

|

Wheelbase

|

1400mm

|

|

Ground clearance

|

n/a

|

|

Seat height

|

840mm

|

|

Dry weight

|

176kg

|

Looking for motorcycle insurance? Get a quote for this motorbike with Bennetts bike insurance

Bike pictured was on sale at Fastline Superbikes, Preston. 01772 902600, www.fastline.co.uk