eb7a.jpg)

Additional reporting: Michael Mann

Imagine if someone made a motorcycle quick shifter that really worked as well as you hoped in every situation? Accurate, seamless gear shifts with the just the slightest tap on the controls. Imagine also if the controls were on the handlebar and so changing up or down, even at full lean angle could be done without fuss or worrying about getting your boot stuck between lever and tarmac?

Imagine also that the same gearbox did away with the need for a clutch lever and, at the lowest of low revs was unable to stall? How cool would it be to filter through slow moving traffic without needing to constantly feather the clutch? How amazing would it be when riding off road to be able to descend a near-vertical muddy slope and just change down a gear without needing to shut the throttle or risk breaking traction by pulling in the clutch lever. And, how good would it be on a big touring motorcycle to change gears up-and-down without your pillion head-butting the back of your helmet?

So, here’s a thing. Honda’s Dual-Clutch-Transmission (DCT) does all of the above and it does them in the most subtly engineered way. DCT is as big a revolution in motorcycle control as it must have been in the early 20th century when gear-changing went from hand controls to feet and clutch control went from foot to hand.

461b.jpg)

Discrete grey paddles on the lhs switch gear control the quickest quick shifter you’ll ever use

DCT, when used in ‘manual’ mode – changing gears with a couple of small paddles on the left-hand switchgear – is just brilliant. Hard on the gas it makes every (and I mean every) other quick shifter on the planet feel clumsy and a waste of money. It’s ability to run at low revs and swap between smooth drive and no drive, without needing a clutch lever is a revelation in heavy traffic. Every set of traffic lights becomes a drag race you know you could win, and two-up riding is a pleasure. DCT should be the device that every single rider has at the top of their options list.

So why do so many riders (and especially so many bike reviewers) hate it?

48f2.jpg)

RHS switchgear selects auto modes (ignore these) and manual option (on the rear of switch cluster)

The answer is simple. The system is built to be an automatic gearbox, not a manual one. Developed by the car industry, the manual shift facility is a sideshow in cars, but absolutely the reason it works so well in bikes. And, sadly, the auto function on Honda’s DCT takes a long time to get used to. It works much better on some bikes than others and, even once you’ve forgotten about it and just get on with riding, there will still be the odd occasion when it is in absolutely the wrong gear at a moment when it really matters.

If Honda had launched DCT as a handlebar-controlled manual quick shifter and not built the auto-function into it, we would have all been raving about it, other manufacturers would have been compelled to build their own version and foot-change gearshifts would already be a thing of the past. Sadly, because it defaults to auto-mode when you engage it, most riders come away confused at best, and usually much worse than that.

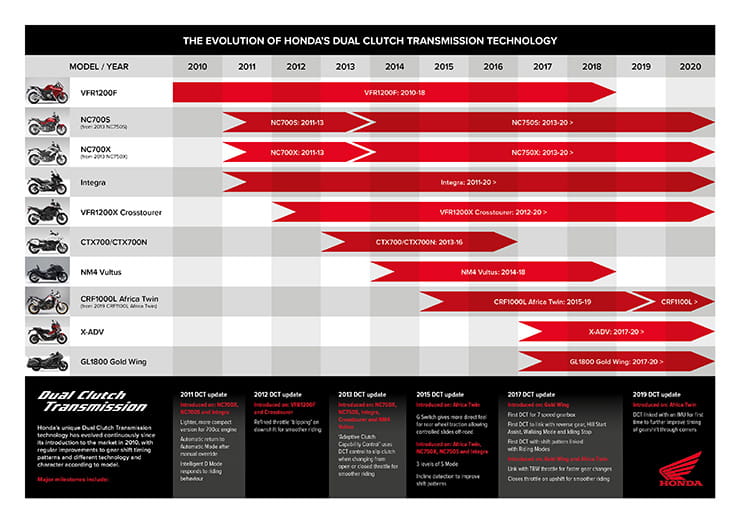

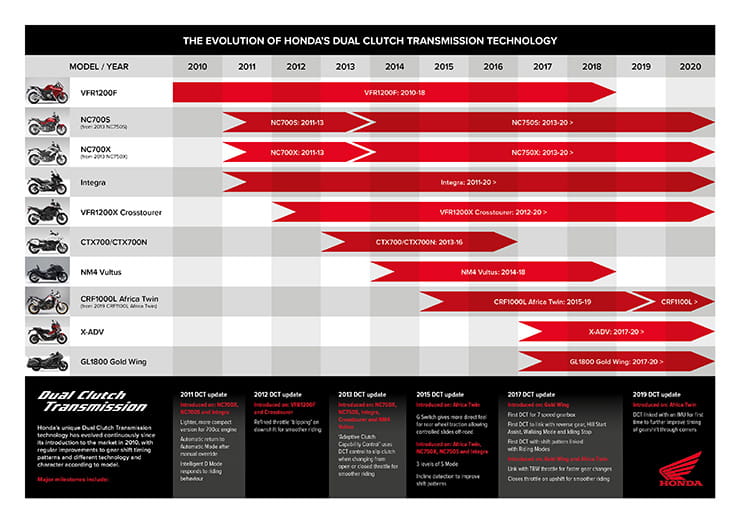

When was DCT invented?

This unique technology first appeared in dealerships across Europe in 2010 on a VFR 1200F, meaning 2020 already marks a decade of existence, during which time over 140,000 Honda motorcycles equipped with DCT have been sold in Europe. In 2019, 45% of Africa Twins and 67% of Gold Wings were sold with DCT which the company puts down to "a constant evolution of the technology, with refinements to the smoothness and timing of the gear shifts."

The system, updated in 2019 to link with an IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit), is available on seven models in Honda's current line-up: NC750S, NC750X, Integra, VFR1200X Crosstourer, Africa Twin, X-ADV and Gold Wing.

How does DCT work?

In essence, there are two gear shafts. One containing gears 1,3 and 5 and the other with 2,4 and 6. Each shaft has its own clutch and the next gear is pre-selected while the previous one is running. This takes the split-second moment of transition out of every gearchange and also makes it much smoother. And because it’s controlled electronically, not physically, there are no microswitches or clunky engineering to cut the throttle etc. Even when you try and fool DCT by manually changing down while still accelerating, the shift is still almost instantaneous and as smooth as you like.

For a more detailed description of DCT’s operation click here.

4777.jpeg)

2010 VFR1200 was the first Honda to get DCT

DCT model history

The first generation DCT launched on the 2010 VFR1200F was awful in auto mode – changing up far too early in the ‘D’ setting and not much better in Sport mode. Honda didn’t help matters by launching DCT on a typical launch-type twisty German mountain route. We were going into tight, slippery (it was raining) second-gear corners with the bike still in fifth gear, only for it to change down to fourth or third right at the wrong moment, leant over, when you’d least expect it.

In manual mode it was brilliant, and I came away converted in part.

By the time the VFR1200 motor arrived in the Crosstourer a couple of years later Honda had sorted out the algorithm and the auto gearchanges were more considered. Because the VFR motor has so much torque it didn’t really matter if you were cornering in fourth because there was enough drive to pull you round.

2016’s reborn Africa Twin seemed a weird choice of bike for DCT, but it turned out to be a stroke of genius. With even better-developed algorithms, the system worked well off-road, even in auto-mode because while navigating bumps, boulders and muddy trenches it turns out that not also having to worry about changing gear is a very good thing.

And by the time DCT hit the 2018 Gold Wing (where it is also linked to the riding modes), Honda had got the system pretty-much perfect.

Above: the history of DCT-equipped Honda models

The only fly-in-the-ointment is on the NC700/750 range, where it works brilliantly in manual mode for all the reasons mentioned above but is awful in auto-mode. It’s the same issues as the early VFR1200; changing up far too early and holding onto gears for too long when slowing down. One simple example happened to me the other day on an X-ADV adventure scooter (which uses the NC750 driveline). Going into a mini-roundabout in the right-hand-lane, at 20mph it had only dropped down to fourth gear. As the road opened-up, the car alongside me needed to overtake a dawdler in front of him and so started to pull out into my lane, having failed to spot the world’s brashest super-scooter alongside. No worries. I cracked open the throttle, but because the DCT had already changed up to fifth gear (at less than 30mph) the not-really-torquey-enough motor just bogged down, accelerating even more slowly than the car alongside.

Without the low-rev drive in high gears that the bigger DCT motors have, the X-ADV was vulnerable.

I could (and should) have just tapped the manual downshift button a couple of times to engage third gear for some brisker acceleration, but I’d slipped into auto-mode and was lucky to get away with it.

The benefits of DCT

"Each model fitted with DCT has different shift timing. For example, the X-ADV is much sportier than on the Integra, as it upshifts at higher rpm and downshifts also at a higher rpm for more engine braking," says Mr Dai Arai, DCT Chief Engineer. He continues by talking about the benefits of the system, "The biggest thing for me is how much brain ‘bandwidth’ it frees up to use on what is most enjoyable about riding – cornering, looking for the right lines, timing your braking and acceleration. The other things is that it is both easy and direct. ‘Easy’ meaning no need to use a clutch in slow traffic, no chance of stalling, no bashing helmets with a pillion. ‘Direct’ being the speed of the gear change, the ability to use the triggers, and, as I mentioned, to concentrate purely on your riding."

Other automatic bikes we ignored

Honda has history with automatic gearboxes. In the late-1970s they built a CB750 and CB400 with proper automatic gears including a car-type torque convertor. Aimed mostly at the American market they were heavier, slower and less economical than the standard manual bikes and more expensive too.

Moto Guzzi also built a car-type auto version of their V1000 in the mid-1970s. it was equally slow, thirsty and uninspiring to ride and also consigned to the quirky side of motorcycling’s historic garage.

16fb.jpg)

Yamaha’s first-generation of semi-automatic FJRs too k a bit of getting used to

Yamaha FJR1300AS

This was an interesting one. The semi-automatic FJR1300 arrived in 2006 and was essentially a standard FJR with a fancy automatic clutch. The rider had to change gear with either a foot lever or hand paddles, but there was no clutch lever and it didn’t stall when you came to a stop.

It also didn’t automatically drop down to first gear at a standstill either, so you had to be careful not to try setting off in third gear.

Once moving the FJR’s system worked well, but at low speeds (filtering through traffic for example) it could be clumsy and clunky. Plus, setting off from rest – getting a heavy 140bhp sports tourer off the line took some practice and U-turns were pretty-much impossible.

The problem was that the just-off-the-throttle response on a bike is critical and, until you don’t have a clutch, you don’t realise how much you rely on it. Honda’s DCT is almost perfect in this crucial area.

c6e8.jpg)

Aprilia’s Mana 850 had a scooter-style CVT with a chain final drive

Aprilia Mana 850

Like an enormous twist and go, Aprilia’s 2007 Mana had a belt-drive, scooter-style CVT (continuously variable transmission), which could either be used as a full automatic or a pseudo-seven-speed-manual using preset positions on the drive cones. The system worked really well and deserved to be more successful than it was. Sadly, the Mana didn’t find a huge audience in the UK.

To hear more about the DCT gearbox and to see one in action, register for the Honda LIVEstream event taking place next week where we introduce the latest Gold Wing and Africa Twin flagship models on the Honda UK YouTube page

Article originally published 24/10/19

eb7a.jpg)

461b.jpg)

48f2.jpg)

4777.jpeg)

16fb.jpg)

c6e8.jpg)