But, it all means that Yamaha has created one of the mentalist superbikes ever to see the road, and yet it all feels somehow controllable.

I say somehow because a motorcycle that makes 185 genuine rear wheel horsepower is never going to be an easy thing to sit on top of.

No matter how many electronic controls you put on a motorcycle, it still needs to be ridden. Yes, bikes get easier to ride in many ways and superbikes of 2015 are in many ways easier to ride fast than bikes of ten years ago.

Anyone who says otherwise has obviously never sat on top of a near 200-bhp motorcycle on the road and tried to open the throttle as far open as they dare for more than a few seconds.

Try to hold the throttle it in first gear and the force of acceleration is so fierce it takes your breath away. It’s all you can do to hold on as it rams you back in the seat and takes off. Hit second gear and it will do 115mph on the 13,500rpm rev-limiter.

I wasn’t brave enough to try and use 100 per cent throttle for very long in third gear, such is the pace it accelerates at, and how quickly the road runs out. The electronics control all this madness in a way rarely seen on a road bike though. Yamaha say that slide control was introduced just two years ago on their MotoGP bikes, and now you can buy a version of it on the road.

But more than that is the way the bike drives. The inline four-cylinder Crossplane crank motor is ultra-flexible with plenty of low-down grunt which turns into rapid acceleration after 6000rpm and then goes turbo by 9000rpm. It’s not ultimately as fast, or as powerful as a BMW S1000RR, and hasn’t got quite the low-down urgency of the Ducati 1299, but it really is margins of how fast do you want when it comes to the top-end. All of them are superb in that respect.

The noise the Yamaha emits is straight from the MotoGP paddock too. Loud, but not offensive. It barks and makes you want to explore higher revs than you need just to hear it roar. It picks up revs so quickly you have to be on your toes. Check our test video for evidence, or watch an on-board lap of Rossi on a Saturday afternoon and I swear the noise is almost the same, except a bit slower of course.

It’s not all brilliant though, it’s incredibly small – 600cc sports bike small in fact – which makes it brilliant on the track but cramped on the road for even average-sized riders. I’m six foot four so was never going to be truly comfortable on any current superbike.

The 17-litre aluminium tank sits you right in the bike, the seat is narrow to allow you to move around. It feels right for action.

The BMW S1000RR has much more leg room, the Ducati 1299 is similar. The suspension on the Yamaha feels firm on the road too, and this adds further to the general uncomfortable nature of the R1.

The Yamaha’s main rivals from BMW and Ducati offer semi-active suspension as an option and this means they ride much smoother on the road. The system essentially read the road based on information sent to the suspension from the Inertial Measurment Unit, so it reacts to bumps, inputs in throttle position, speed and lean angle. It means you always have the right suspension setting at the right time and give a high-quality supple ride on the road, or a firmer ride when you need it.

To get semi-active suspension on a Yamaha you need to buy the Yamaha R1M and they’re all sold-out. It’s a shame that you can’t get it as an option on the road bike.

Yet, ultimately, on the bike’s limit you get more feedback and feeling from the Yamaha on track from its suspension, but that’s the compromise I guess.

Other small issues on the road? Well, the fuelling is slightly snatchy at very low revs (below 3000rpm) in either Mode A (extreme, full-power use), or even in Mode B (more road-friendly but still full power). Admittedly I never used Mode C or D. It’s only noticeable when riding slowly, behind traffic, and in town and you soon learn to expect it. It’s thirsty too – we were getting 27mpg average which means a tank range to empty of 100 miles when ridden hard. Ultimately, we were riding it incredibly hard during this test so more normal riding you could expect 35-40mpg and a more reasonable 130-150mile tank range. The Ducati makes a similar mpg, the BMW does mid-40’s on the road. But if these are the kind of issues that affect you, don’t buy a 200bhp Superbike. Simple.

Small niggles aside, the rest of the time the motor is sheer perfection on the road. Noise, power, grunt it’s always where you want it. The gearbox is positive on the downshift (though doesn’t use the auto blipper downshift systems that the BMW and Ducati have), and the quick shifter makes a lovely, racey style exhaust pop on the upshift, delivering a seamless growl of intoxicating noise. The quickshift works from as low as 30mph faultlessly.

We’ve talked about the cramped riding position – but then this is a MotoGP derived race bike for the road, so what should we expect. But in every other way the Yamaha works. The mirrors work, the TFT screen (using mobile phone screen technology) gives perfect clarity, the modes are easy to use, the brake lever is span adjustable, even if the clutch lever isn’t, and the menus are easy to use and change the array of settings to turn it in to your bike.

Want more or less traction control? Fancy a bit of slide control for the track? Or don’t want wheelie control? Just set it up how you want.

The electronic systems are a marvel. You know they are working, but they never take over. Within 40 miles I started putting my ultimate trust in their ability and started taking liberties. As a fan of bikes on one wheel, I was worried by the LIF wheelie control, but as I started to ride faster it made total sense. You just use the throttle to make maximum forward progress without dancing on the throttle to lay down all of that horsepower and keep the front wheel down. It just drives with the front wheel hovering above the ground, again, like Rossi exiting a corner.

Few road bikes I have ever ridden have given me as much of a grin as the Yamaha R1. It’s right up there with bike of the year, that’s for sure. But then the Ducati, and the BMW S1000RR are hardly rubbish. I’d take any one home given the chance.

But there’s something about the R1 that feels special. Admittedly, when I was at the bike’s unveiling in Milan, I was worried by the bike’s styling. As MotoGP-inspired as it is, I couldn’t help thinking that it doesn’t say R1 in its lines clearly enough. It doesn’t follow that glorious evolution of styling that started back in 1998 with the original twin-headlight R1. But what it does do is follow the lines of the YZR-M1 and insert LED riding lights, and those tiny LED projector headlights.

But the lack of a traditional front headlight and those LEDs grow on you the more you spend time with it. It looks like nothing else this side of MotoGP paddock, and is completely unique. It doesn’t need to look like an R1 to be an R1. It’s Yamaha’s ultimate show of their power and technology, it’s the ultimate hardcore sports bike experience right now – exactly what the original R1 stood when it was launched 17 years ago.

THE TRACK:

IT’S exiting the fourth gear corner on to the Hangar Straight that I realise something big just happened.

I’m hanging on to 100 per cent throttle earlier, harder, and more than any other bike I’ve ever ridden on track as the electronics do the work. It’s on the stop way earlier than my skill level, or horsepower should allow. Okay, you’ve still got to ride the bike, but it’s easier to go fast on track than anything else in its class. It gets out of a corner faster using all its electronic gremlins. But I also gets into a corner faster, holds more mid-corner speed too.

As I’m lucky enough to be the only person on Silverstone’s full GP circuit (please don’t send hate mail), I can see the black lines the bike is leaving from the rear tyre after every lap painting a dot-to-dot R1 tour of the circuit. It gathers incredible momentum, lets the rear of the bike slide just enough, lets the front wheel leave the ground by a couple of inches and lays all that power down through the super grippy Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa SP 200-section rear tyre. There’s occasionally a little flick from the bars as the sliding rear hits a bump, but mostly it’s dead stable too, perfect on the way in to a corner and gives incredible feel when leant over. That’s some feat.

On the straight, you can get tucked in then bang on the brakes hard. They’ve got braided hoses, linked front and rear brakes, and ABS. The six-axis Inertial Measurement Unit knows the attitude of the bike in six different directions, knows how much brake you can have going in to a corner.

Our bike had done a few speed runs at Bruntingthorpe runway from a recorded 182mph, and a hard track work out and there was never any fade from the brakes.

Nail the brakes hard and there’s total feeling from the last piece of travel in the front fork. Some of the semi-active set-ups still leave you guessing when you get to the end of the fork’s travel. They feel a bit dead on the limit, not this with its old school KYB set-up.

Go hard down the gears and the slipper clutch does a great job of locking the back wheel up and prevents it lifting. Only once did I have the back wheel go light and come round on me when on the way in to the complex.

The aluminium twin spar chassis also features magnesium for the subframe, with the same geometry of the old R1, but a 10mm shorter wheelbase with a 15mm shorter swingarm than the bike it replaces. For the record, the only thing it shares with the older bike is the name.

Incredibly for a production road bike it has lightweight magnesium wheels too – a first.

It gets into a corner incredibly quickly with very little effort and feels neutral. Once you’re in, there’s no feeling of running wide, or a vague, slightly loose front-end that old R1s are famous for. It just allows you to tighten your line, haul it in right until the footrests touches down. Even then, at incredible lean there’s total feel for what the bike is doing.

On the road, the BMW might be the more rounded package, but on the track there’s nothing that can touch the finesse and adjustability and feel of the R1 – even the incredible 1299 – although the Ducati will run it close. As good as that red bike is, it always makes you work ever so slightly harder for your lap time than the Yamaha. I only rode the Yamaha on standard suspension settings too, yet didn’t need to change a thing in the sessions I had.

What it lacks in comfort on the road, it more than makes up for with its blistering pace on track. It’s next level experience.

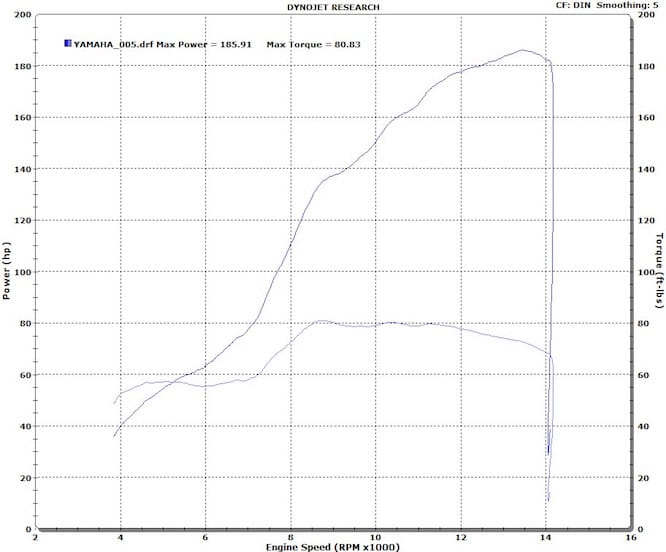

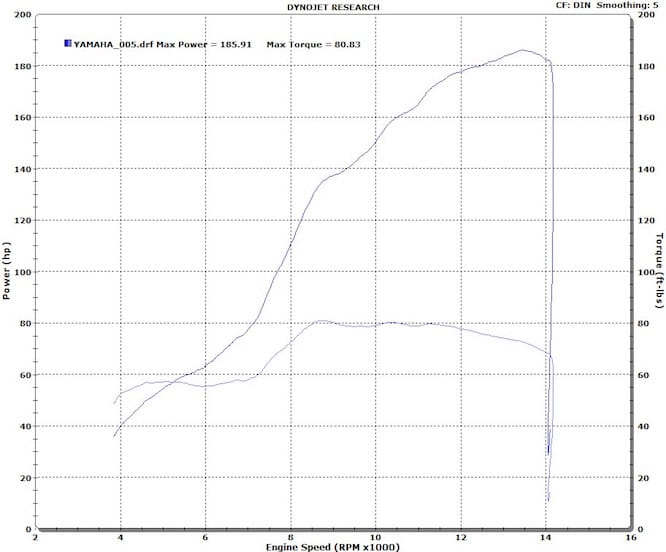

ON THE DYNO:

To test the R1’s true power and torque output we put the R1 on the dyno at BSD, one of the most experienced dyno outfits in the country.

So, the headline figures are: 81.27ftlb of torque, and 185.91bhp at the rear wheel, but that’s not the full story.

Interestingly, BSD said the bike has a soft rev-limiter in sixth gear which stops it revving out to its full potential, limiting the revs by 800rpm to 12,700rpm. In sixth it hit a maximum power of 180.64bhp and made 81.27ft-lb of torque.

As the bike had been restricted in sixth gear, we dynoed the bike in fifth gear, in Mode A with no traction control. Revving out to 13,500rpm allowed the bike to hit its maximum peak power output of 185.9bhp at 13,500rpm.

MORE

Yamaha claims 200bhp at the crank with ram-air, but that kind of air-flow obviously can’t be replicated on the dyno, unless you know anywhere where we can replicate a 180mph wind in a dyno room.

The bike gives its maximum torque of 81ft-lb from 8500 to 12,500rpm. The electronics are so clever that it will not let you have full 100 per cent throttle until you’re at 10,000rpm in any gear.

SECOND OPINION: BRUCE DUNN, NATIONAL RACER & MCN TESTER – SECOND OPINION

Bruce has tested every bike known to man for MCN over the last 20 years, won National race championships, entered the British 250GP as a wildcard, and recently helped MCN with their big sports bike group test, where the R1 was crowned the winner. Here are his thoughts:

The all new R1 feels different in every way from the previous model, it feels taut, light and agile. The engine makes more power particularly in the higher rev range.

With regard to performance testing, the R1 exhibited virtually no issues. Quite often on maximum acceleration we find that stability can be compromised especially in the lower speed range where the front wheel is barely in contact with the ground. The R1 gave no handlebar kickback (tank slapping ) or ' nervous' twitchiness. Towards the end of the speed range around 180 mph the R1 remained composed and settled even when being steered or changing direction.

The 'feel' and comfort at high speed was perfect, the riding position needed no 'morphing' (sometimes at high speed it's necessary to move yourself back to tease the best out of the aerodynamics. The airflow was smooth with minimal buffeting across the entire speed range.

The brake test we perform is maximum effort at the lever with complete reliance of the electronic ABS making the best of the braking whilst effectively taking the rider out of the loop, other than to balance and correct any steering.

The braking figures we achieved were mediocre, this reflects more on the simplicity of the test rather than the full potential of the brake system. Because the brake system is so advanced it would take some thought as to how to test the brakes, ABS and cornering braking are areas where the R1 is claimed to be superior. I feel a test that would incorporate these elements could establish a baseline or reference, for future testing.

But what really sets it apart, not only from its predecessor but other litre sports bikes, is the way it rides when pushed. And it needs to be pushed; the chassis and electronic power management controls all start to harmonise and work together at quite a high level, of both rider and mental effort. For example, in our performance testing we turn the wheelie control level to off. Not because it doesn’t work, but because it’s not really designed for our 'Drag race' like 0 – max speed test.

Speed Time

MPH (SEC)

0 - 60 3.20

0 - 100 5.87

0 - 180 19.11

BRAKING

Speed Time

MPH (SEC)

70-0 3.68

If left on the ECU will cut the power two or three times until enough forward momentum is logged, the symptom of this is the front wheel will pop up and down as if a novice is trying to wheelie.

However when ridden normally, whether it be on the track or road, the function of the electronic power management is exquisite. The wheelie control seamlessly and smoothly allows full throttle acceleration without being trimmed or managed in any way by the rider, if you’re in the lower gears the power is dispensed precisely to allow only a smooth exact levitation of the front wheel, on level two the wheel would stay around 3 – 4 inches of the ground with full throttle all the way through 2 to 3rd gears, just like you see Rossi do it when running onto and down the Valencia start finish!

And that’s just one element of the R1. Again when being ridden aggressively on the track the bike feels so settled, in all areas of attack. Its one thing having good traction control, but what’s the point the bike is fighting you at the handlebars. The chassis and power delivery combine to make the bike feel neutral and settled particularly creating an enhanced feel into turns. The thing that makes most riders faster than the next is usually in this area of corner entry. Yamaha have got the chassis working with engine in a way that gives the rider confidence. Late and deep braking with unshakeable stability whilst lent over is major factor in making the R1 feel superior to other litre sports bikes.

|

Engine type

|

liquid-cooled, 4-stroke, DOHC, forward-inclined parallel 4-cylinder, 4-valves

|

|

Displacement

|

998cc

|

|

Bore x stroke

|

79.0 mm x 50.9 mm

|

|

Compression ratio

|

13.0 : 1

|

|

Maximum power

|

147.1 kW (200.0PS) @ 13,500 rpm

|

|

Maximum torque

|

112.4 Nm (11.5 kg-m) @ 11,500 rpm

|

|

Chassis

|

Aluminium Deltabox frame

|

|

Suspension

|

Front: Telescopic forks, Ø 43 mm, 120mm travel, 24 degree caster angle, 102mm trail

Rear: Swingarm, (link suspension), 120 mm travel

|

|

Brakes

|

Front: Hydraulic dual disc, Ø 320 mm

Rear: Hydraulic single disc, Ø 220 mm

|

|

Tyres

|

Front: 120/70 ZR17M/C (58W)

Rear: 190/55 ZR17M/C (75W)

|

|

Dimensions

|

L: 2,055mm

W: 690mm

H: 1,150mm

|

|

Seat height

|

855mm

|

|

Wheel base

|

1,405mm

|

|

Weight (wet)

|

199kg

|

|

Fuel tank capacity

|

17 litres

|

|

PRICE

|

£14,999

|

A huge thanks to Silverstone for the track time! You too can ride the full Grand Prix circuit at their GP track day on 5th May - find out more here.

Got your eye on a new R1? Or do you own an older model?