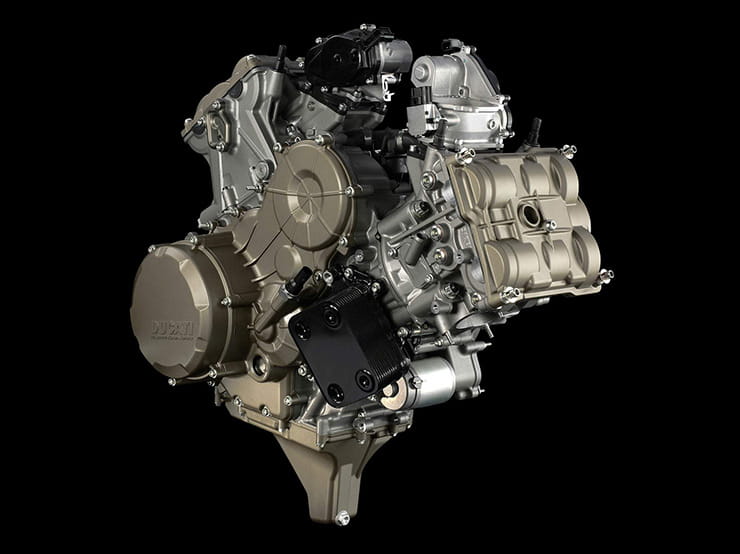

The new Ducati V4 superbike is without doubt in line to be the most exciting new bike of 2018. It will be insanely fast and offer MotoGP technology for an almost-affordable price. On the face of it there’s much to be excited about but there’s a downside as well, since it will mark the end of the V-twin configuration for top-level superbikes.

And for the bike-buying customer, that’s a big shift. From 2018 onwards, it’s likely there will be no cutting-edge, race-bred V-twin superbike on the market.

It won’t be a cold-turkey elimination of the V-twin configuration. Most of Ducati’s range will still be twin-powered for many years to come. But once the Ducati V4 is on-stream, twins will no longer power the firm’s top-line superbike, and that inevitably means that they will begin to lag behind in terms of development. And since every other firm making V-twin superbikes has either dropped the configuration or folded completely, it means there’s a whole market category disappearing.

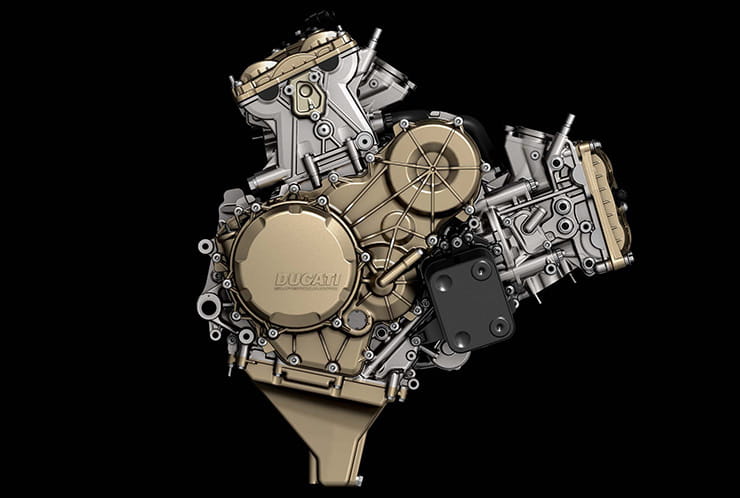

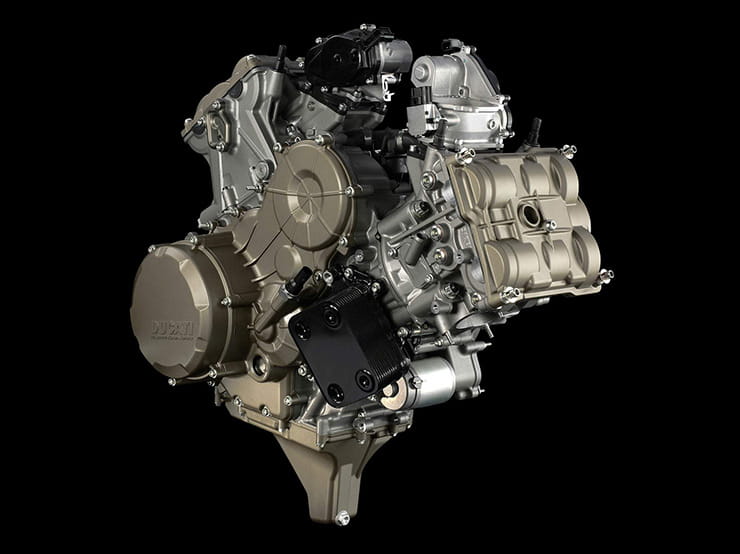

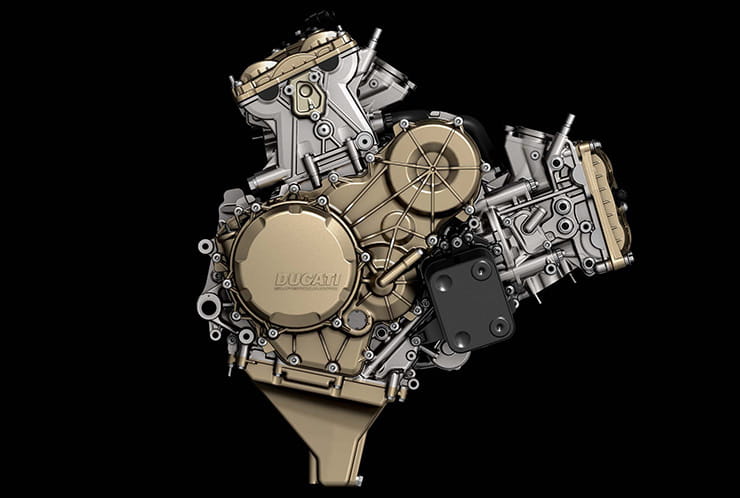

Ducati’s shift to a V4 is no surprise. It’s raced the similarly-configured Desmosedici for 14 years in MotoGP, and even had production bike V4 success with the Desmosedici RR. But the move to the V4 engine for its range-topping mainstream superbike means that for the first time since the dawn of the modern superbike era, as defined by the WSB championship that started in 1988, come 2019 there won’t be a V-twin on track. And that means there won’t be a true V-twin race-rep superbike on the market, either.

Ducati has, without doubt, done a lot of analysis into its move to a V4. While now a regular race-winner, the Panigale has struggled to become a competitive WSB bike since its introduction, and that’s largely a reason behind the move to the same 1000cc four-cylinder configuration as all its rivals. But some have suggested that the Panigale’s struggles were less to do with its cylinder count and more a result of Ducati’s single-minded quest for power.

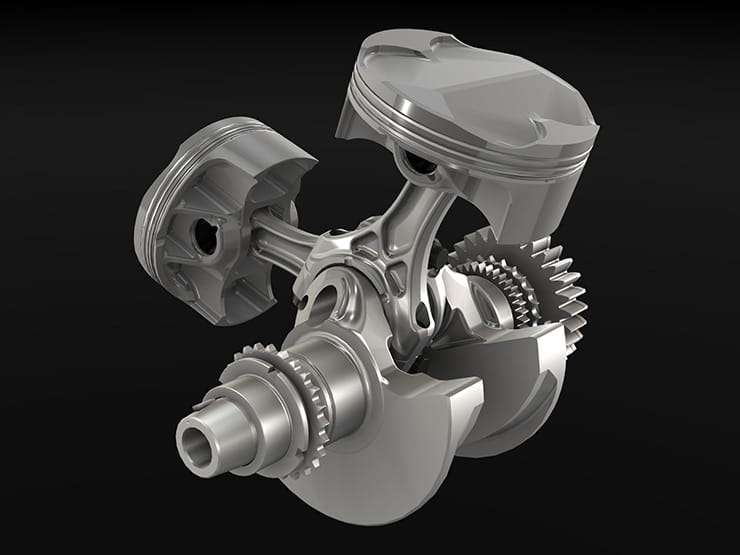

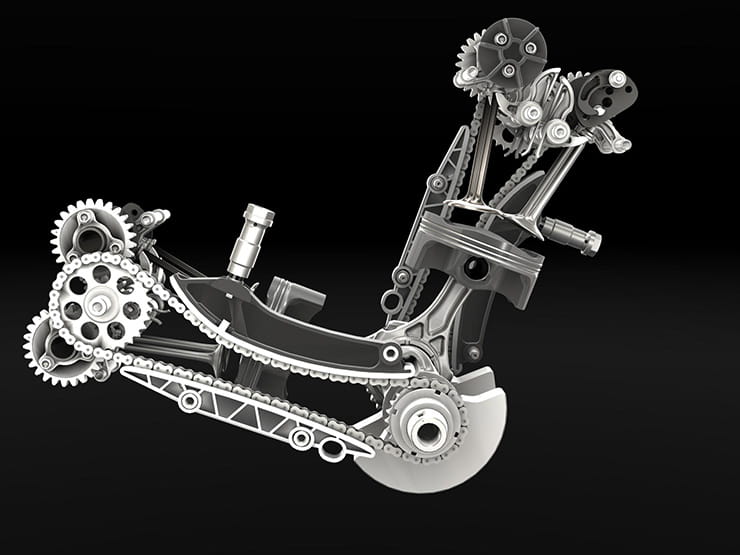

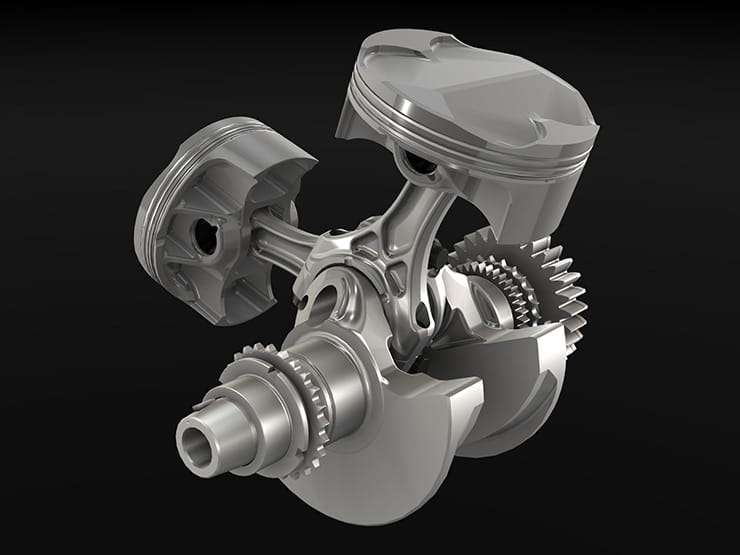

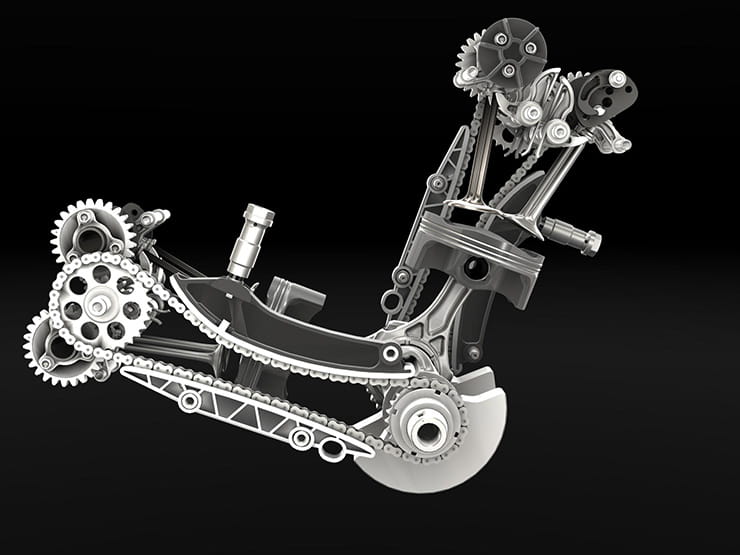

The Panigale’s ‘Superquadro’ engine is an engineering masterpiece. It’s an incredibly over-square design, with a 60.8mm stroke and either a 112mm bore (for the 1198cc ‘R’ model) or an even bigger 116mm bore on the 1285cc 1299 Panigale. That’s approaching a 2:1 bore-to-stroke ratio, which allows for a massive valve area and far higher revs than a more conventionally-proportioned V-twin.

Lots of valve area and lots of revs are traditionally areas where a four-cylinder has an advantage over a twin. Combined, they have long allowed fours to have more peak power than a rival V-twin, even taking into account the additional capacity that racing regulations have long allowed two-cylinder bikes to have over their four-cylinder rivals. The Panigale, though, has no power shortfall, either in production form or as a racer, so why is it the only generation of Ducati V-twin since the dawn of the WSB series in 1988 not to win a title?

Some suggest that, in pursuit of four-cylinder-rivalling peak power, Ducati has already thrown out the less tangible benefits that helped so many of its earlier twins to racing silverware.

Whether it was the 851, the 888, the 916, 996, 998 or 999, the 1098 or the 1198 that was the last Ducati to take a WSB title in 2011, all had peak power deficits to their four-cylinder rivals, but benefitted from a magical ability to find grip where others couldn’t, and to punch out of corners faster than the fours.

To look at that in straightforward numbers, the 1198 R – already a high-revving, over-square twin – achieved a peak power of 180bhp at 9750rpm and peak torque of 99.1lbft at 7750rpm. The Panigale R manages 197bhp, but not until 11750rpm, and its peak torque of 95lbft is actually lower than its predecessor and isn’t reached until 10,250rpm – 2500rpm further up the rev range. Some Ducati fans have been outspoken in their dislike of the Panigale’s power delivery, which they say is too much like a screaming four-cylinder rather than the thumping twins they previously loved.

A rival argument suggests that the twin’s out-of-corner advantage has been eroded not by its own shortcomings but by improvements from its four-cylinder rivals. Certainly, traction control has come on in huge leaps in recent years, and could well be behind the recent successes of four-cylinder bikes – particularly the Aprilia RSV4 and Kawasaki ZX-10R in WSB racing terms over recent years – in beating the Ducatis.

While the new V4 Ducati is already guaranteed legendary status – it’s a GP-derived road bike, and one that will be far more affordable than previous bikes to carry that tag – it’s unlikely to answer the complaints of those who already miss the low-rev thump of Ducati’s past superbikes.

This isn’t a criticism of Ducati, though. The firm’s analysis has clearly led it to believe that, despite the capacity advantage offered to twin in WSB racing – 1200cc against 1000cc for four-cylinder bikes – it needs to join the herd if it’s going to be competitive in the long term.

As the last bastion of the V-twin superbike manufacturers, Ducati can’t be accused of not trying to keep the two-cylinder flame alive. But with no other company currently making a two-cylinder superbike or showing any interest in developing one, it is consumer choice that eventually suffers from the focus on racing.

Given that superbike development has long been driven by the needs of racing, it’s surprising that four-cylinder machines have reached the position where they’ve completely eliminated their twin-cylinder rivals. History suggests the battle should have gone the other way.

There have been 29 full seasons of WSB racing since the championship started in 1988. Ducati twins have taken the manufacturers’ title 15 times and the riders’ championship 14 times. Twins overall account for even more wins – include the successes of Honda’s VTR1000 SP and SP2 and they account for 17 manufacturers’ and 16 riders’ titles.

Four-cylinder bikes have, generally, struggled to compete. Before 2005, the only fours to win manufacturers’ titles were the ultra-exotic Honda RC30 and RC45. And even since 2005, only four four-cylinder models have taken manufacturers’ titles – one each for the Suzuki GSX-R1000 and Yamaha R1, three for the Aprilia RSV4 and three for the Kawasaki ZX-10R.

However, since 2012 – the year that the Panigale was launched – the WSB championship has been a four-cylinder whitewash, with title wins in both the riders’ and manufacturers’ arenas split between Aprilia RSV4s and Kawasaki ZX-10Rs.

But is that recent four-cylinder dominance down to an advantage for the configuration, or a failure from the one remaining twin in the series to live up to its potential?

It all nearly went very differently. Before 2004, when the regulations were changed to allow 1000cc four-cylinder bikes to compete, twins were increasingly the favoured option for superbikes.

Not only were there several generations of Ducatis, but we saw Honda develop the VTR1000 and the SP and SP1 racing spin-offs, Suzuki making the TL1000S and TL1000R and Aprilia getting plenty of success with the RSV Mille.

At that time, of course, twins had a capacity advantage, with 1000cc two-cylinder bikes allowed to compete with 750cc fours. In 2004 that discrepancy was eliminated, with a 1000cc blanket limit applying to WSB racing, but even then Ducati’s 999 achieved the seemingly impossible, remaining competitive and taking two riders’ and two manufacturers’ titles, in 2004 and 2006. With a new capacity advantage offered for 2008, since when twins have allowed 1200cc to compete against 1000cc fours, Ducati again took both titles with the 1098. The 1198 won the manufacturers’ title in 2009, too, and took both championships in 2011.

What all this history makes abundantly clear is that, aside from occasional rule tweaks in WSB altering the balance of power slightly from one year to another, twins have always been a powerful force in superbike racing. And that’s something that’s been mirrored in their road-going derivatives. To argue that a Panigale is in any way inferior to its four-cylinder production bike rivals would be a lost cause. And the same applied in earlier years, whether talking about previous Ducatis or the shorter-lived V-twin machines from Aprilia or Honda (we won’t mention the Suzuki TL1000R; some bikes are just born bad…) Twins make for great superbikes, it’s as simple as that.

Despite all that history, and the fact that it should be quite possible to build a V-twin superbike that can still be competitive in WSB – something that the Panigale is belatedly proving this year – the twin-cylinder format will be largely abandoned in top-line superbikes when Ducati switches to its four-cylinder.

For road bike buyers, the market will also be narrowed with that move. While there are indications that Ducati will keep a version of its 1299 Panigale engine in production – it’s created a Euro4-emissions legal version for the Superleggera and the 1299R Final Edition, which suggests it has a future – after it launches the V4 then there’s little chance that we’ll see the same level of twin-cylinder development that Ducati has almost single-handedly sustained over the last decade or so.

For those of us who prefer the grunt of a big twin over the frenetic scream of a four, and who like to have a race-developer superbike in the garage, that’s likely to be a painful loss.

While there’s a chance that twin-cylinder superbikes will make a comeback, it would require a change in racing regulations and a massive investment from manufacturers. Neither seems likely at the moment.