Whenever air-cooled engines are threatened with extinction Honda’s ingenuity and dedication to the cause gallops to the rescue, and just as forthcoming Euro 5 emissions rules are looming on the horizon the Japanese firm appears to be developing a new generation of air-cooled CB1100 to face them.

A dozen years ago when the CB1100 first appeared as a concept the idea of developing a new large-capacity, air-cooled, four-cylinder bike showed the sort of contrarian attitude that has been the signature of many of Honda’s best bikes. Even then, emissions legislation appeared to be sending air-cooled machines to the grave, just as it has dispatched two-strokes a few years earlier. Inline four-cylinder air-cooled engines were seen as particularly challenging; in 2007, the same year that the CB1100 broke cover as a concept, the last of the mass-made air-cooled four-cylinder, Suzuki’s Bandit 1200, was replaced by a water-cooled successor.

It took until 2010 for the CB1100 to reach showrooms, and despite its retro appearance Honda had poured a vast amount of innovative engineering into its DOHC four-cylinder, 16v engine, ensuring that it could meet not only the then-current Euro 3 emissions limits but that it would also pass the Euro 4 regulations that were due in 2016.

But that was nearly a decade ago now, and next year we’ll see the introduction of Euro 5 emissions rules that once again pose a challenge to air-cooled engines.

There would have been no shame in Honda throwing in the towel with the CB1100. After all, it’s been on sale for nearly a decade and, while selling steadily, it’s not a model that Honda couldn’t live without.

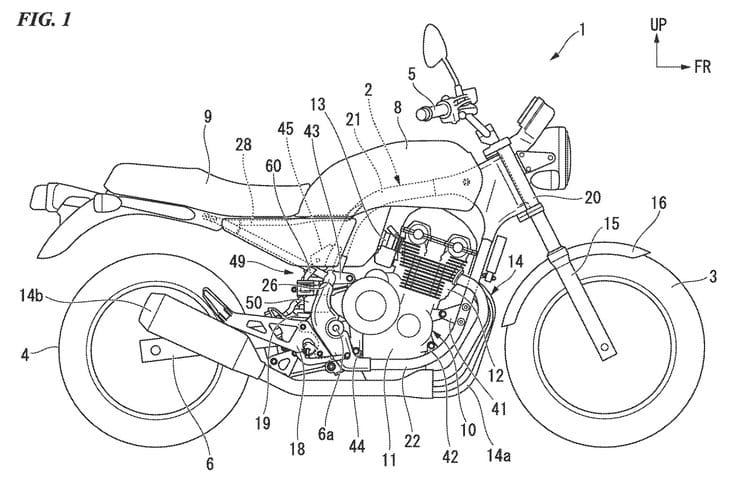

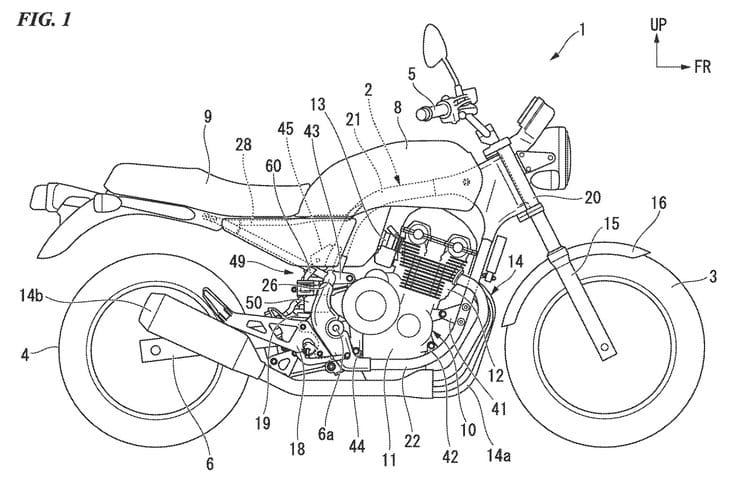

But these new patent applications suggest Honda isn’t about to kill the CB1100, and instead is planning a lighter, better version of the bike. The images here clearly show the new model’s outline, which doesn’t move too far from the existing version in terms of style but does show some distinct technical changes.

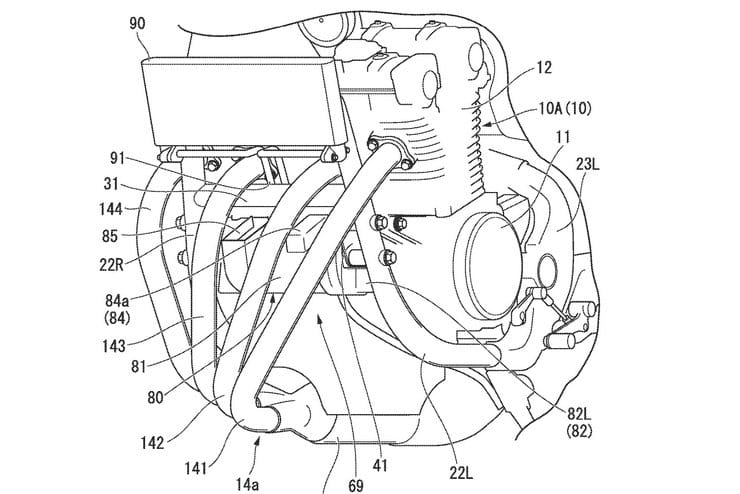

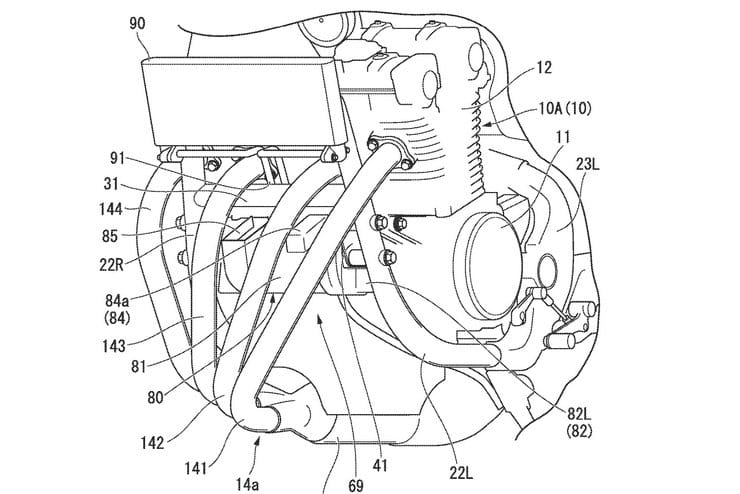

Let’s start with the engine. While the top-end looks much the same as the current model, with the same air-cooled DOHC cylinder head, there appear to be changes to the bottom end, with a smaller clutch cover that hints at changes to the transmission. The exhausts are also new, with header pipes that sweep across to the right hand side, a little like the current CB650R or the 1970s CB400F, gathering into a single end can.

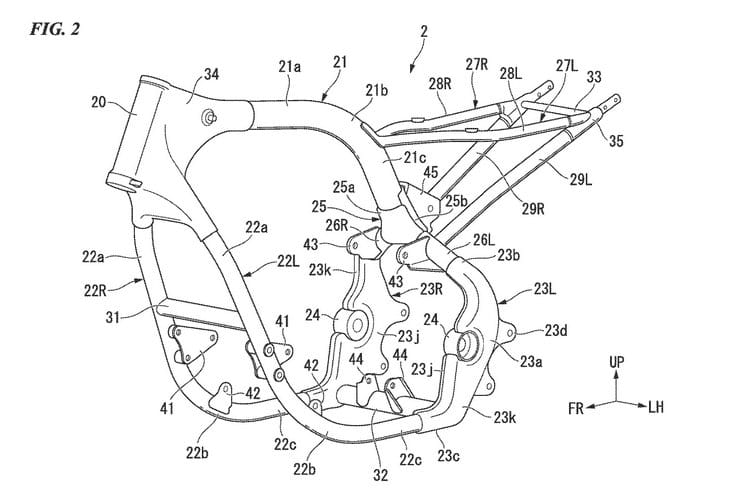

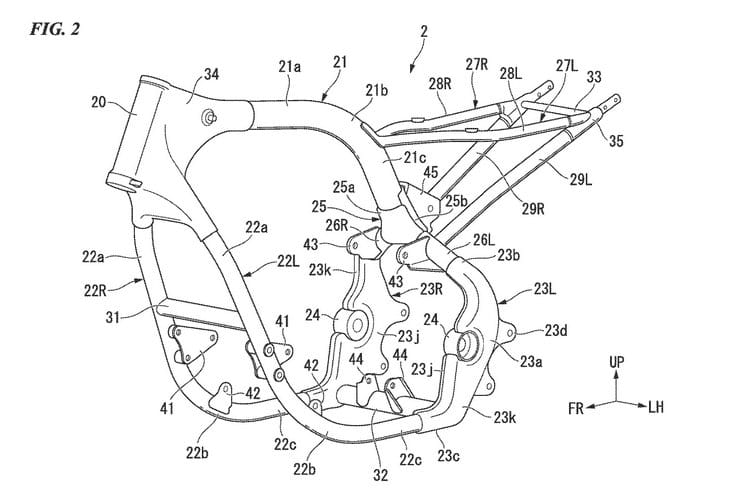

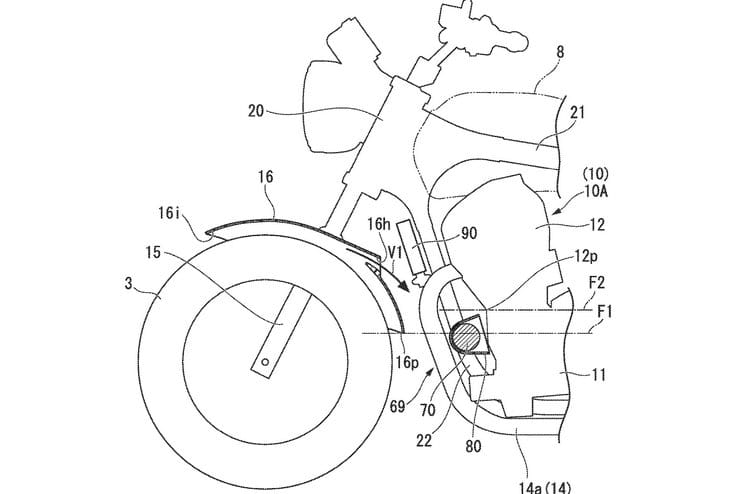

But the engine changes are minor compared to the alterations seen on the chassis. The current CB1100 has a full duplex frame, with two steel tubes running up and over the engine to the headstock, and another two cradling the motor from underneath. That design has gone in these patent images, replaced by a half-duplex frame that keeps the two under-engine cradles but has a single, thick spine running over the top. In many ways the design is more ‘authentic’ than the existing CB1100’s chassis, as the original CB750 featured a half-duplex backbone chassis.

Not that this bike is a slavish copy of its earliest ancestor. Far from it, in fact, as the other major change is the decision to ditch the twin rear shocks used by the current CB1100 in favour of more effective and efficient monoshock, complete with a rising-rate linkage. That change promises a leap forward in ride and handling compared to the existing model.

The seat subframe is also different, triangulated to a point higher up above the swingarm pivot, near the monoshock’s upper mount. That makes for a significant visual change for the bike, with a lighter appearance for the rear end.

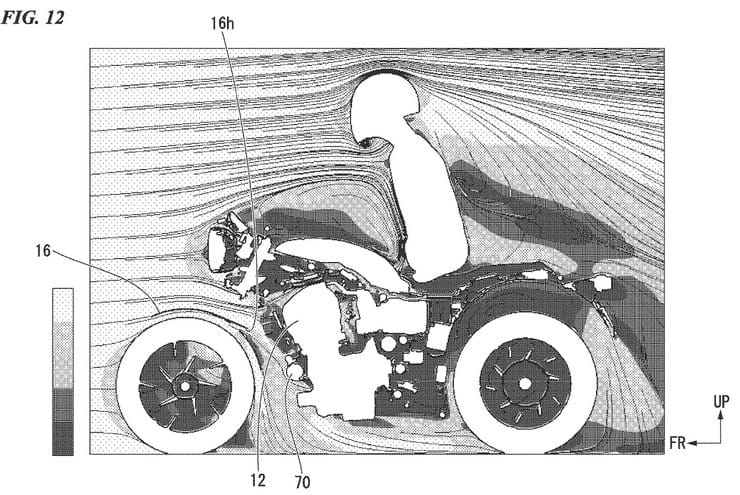

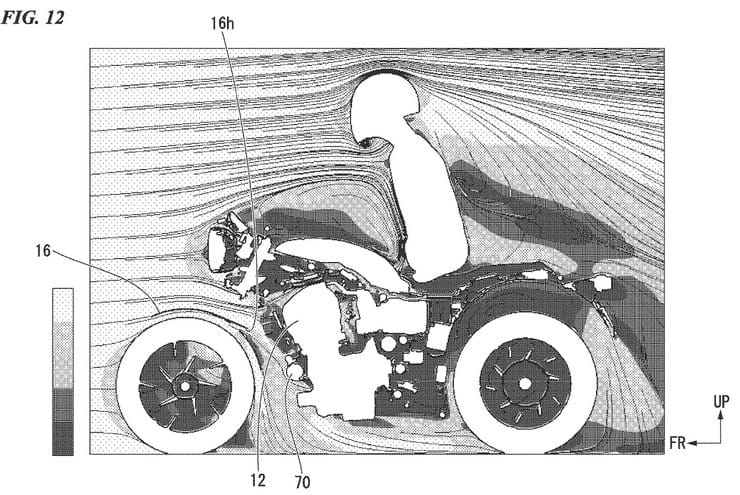

As you might imagine, airflow is vitally important in making an air-cooled engine work. Many of the existing CB1100’s design innovations are based around the way it allows air to flow past the cylinder head’s fins, with a particular focus on keeping the exhaust valves from getting too hot.

On an inline engine like this, cooling the two middle cylinders is a particular problem. Not only do they have less external surface area to put fins on (compared to the outer two cylinders), but the flow of air hitting the middle part of the engine is blocked by the front wheel. That means the middle cylinders are likely to run significantly hotter than the outer two, posing another problem for engineers looking for stable engine temperatures to help their quest for improved emissions and performance.

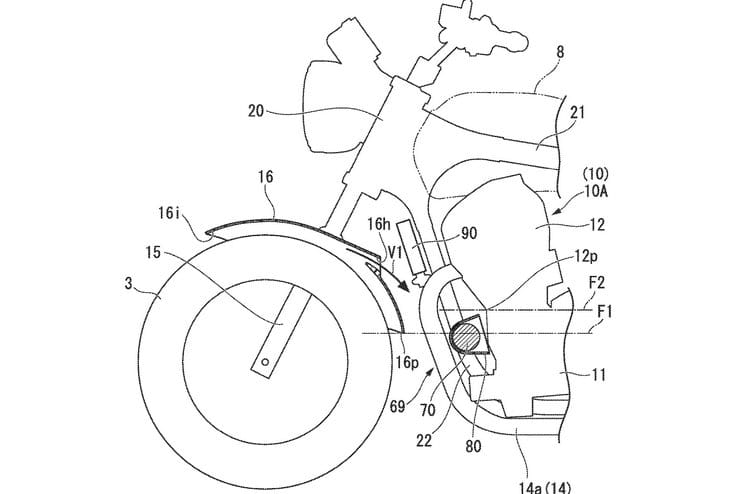

To solve the problem, it appears that Honda is working on a system that uses the front mudguard to help scoop air, ejecting it through a vent that focusses the flow towards the centre two cylinders.

The same jet of air also cools the bike’s charcoal canister, which is part of the evaporative emissions system. It’s plumbed into the fuel tank to absorb vapours from evaporating petrol, and while it’s something that’s already used on the existing CB1100, one of Honda’s patent applications is specifically about the decision to reposition it to the front of the engine on the new version.

Positioning it centrally helps with the bike’s balance, but Honda’s patent text also says that this design will improve both the cooling of the charcoal canister and the engine’s cylinders, thanks in part to the air-diverting mudguard design. The firm has even gone as far as showing computer-simulated airflow diagrams of the design.

Although a patent application can’t be taken as concrete proof that a new bike is coming, in this case the circumstantial evidence is convincingly strong. Not only do the upcoming Euro 5 emissions rules demand updates but Honda is currently marking the 50th anniversary of its CB750 – the first four-cylinder production bike it ever made and the direct ancestor of the CB1100. A new version of the CB1100 would be the perfect way to top off the celebrations.

Given all the problems that air-cooling raises, you might wonder why Honda persists. Certainly, a water-cooled bike could be much more powerful, but Soichiro Honda himself was fanatically devoted to the idea of air-cooled engines, preferring the light weight and simplicity they offered compared to the additional mass and components that water-cooled engines need. He long believed that, with the right design, air-cooled engines could offer just as much performance, too, even going as far as developing an air-cooled Formula 1 car – the ill-fated 1968 RA302. Many of the firm’s early cars were also air-cooled, and there wouldn’t be a water-cooled Honda bike until the Gold Wing appeared in 1974.

It might be hard to justify air-cooling for performance reasons these days, but Honda’s heritage is entwined with the idea. Seeing the firm work to extend the life of air-cooled multi-cylinder engines even in the face of emissions rules that seem dead-set on eliminating them is a reminder of Honda’s rare ability to use its engineering expertise to follow unusual paths, and anything that maintains the diversity of bikes on the market has got to be welcomed with open arms.