Swiss Tease!

Perhaps the best Kawasaki museum in the world is based in Switzerland – though it's not open to the public. But our man Alan Dowds got the chance to go and visit, to celebrate 50 years since the firm's Z1 was launched, back in 1972.

What do you think of when I say 'Switzerland'? Toblerone obviously, plus skiing and rampant neutrality, I guess. Secret bank accounts and legendary Nazi gold hoards? Why not, eh?

But the posh Alpine nation is hiding something a lot more interesting than any of that. Perhaps bizarrely, it's the location of the most amazing private bike collection I've ever seen – and it's filled entirely with Kawasakis. Based at the Akashi firm's Swiss/Liechtenstein importer FIBAG, an hour from Zurich, this assortment of machines was plucked from the thousands of new models delivered there each year. It includes almost every model from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, and loads more, all lined up inside a slightly non-descript office building.

It's almost a scientific archive too: every bike is totally unused, with the only kilometres on the odometers coming from being pushed around the museum floor. The engines have never been run, and there's no oil or petrol inside the bikes: even the brake fluid was drained from new – partly to avoid degrading the systems, partly to reduce maintenance requirements. Fork and shock oil aside, these machines are all completely dry – and exactly as they left the factory, decades ago.

The models on show include the usual suspects: the original Z1 which we're here to celebrate, the H1 500 and H2 750 two-stroke triples, the 1960s Samurai two-stroke twins, and later beauties like the Z1300 inline-six, GPz1100 and an early ZXR750. But it's the less-exotic machines here which really catch my eye. I've seen loads of immaculate H2s and Z1s in recent years – go down to Box Hill on a sunny Sunday and you're guaranteed to see a few. What you won't see is a zero-mile 1987 GT750 in metallic gold, with the original pipes and even the OE tyres. I passed my test in 1989, and bikes like the 78bhp shaft-drive GT were part of the furniture back then. But it's years since I've seen one at all – never mind an utterly brand-spanking new version. Virtually no-one would go to the effort and expense of restoring a bike like that – and nobody would buy one and keep it in the crate like they might with a Honda RC30 or Kawasaki ZXR750R. It's a bit like a zero-mile 1982 Ford Sierra 1.6L compared with an immaculate RS500 Cosworth. As a result, bikes like this, the Z400 and Z200, KMX125, KH125 and the other mundane machines scattered round the museum are all far rarer in this condition than a posh GPz1100, Z1-R or Z1300.

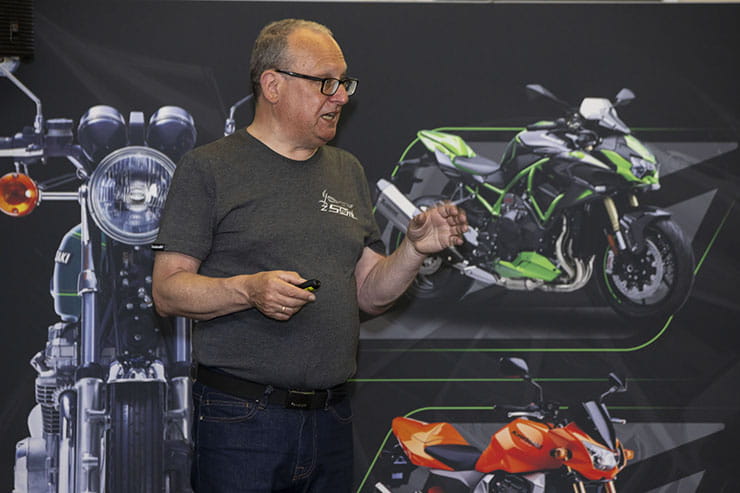

Once I've spent an hour or so walking around this Aladdin's Cave of Kawasakis, tongue hanging out, it's time to sit down and learn a bit more about the original Z1 launch. Kawasaki Europe's marketing manager, Mr Martin Lambert, is here, and what he doesn't know about old Kawasakis genuinely isn't worth knowing. Especially today: he's spent the last few months trawling the Japanese firm's archives for obscure lore on the Z1's development, and takes us through what he's found.

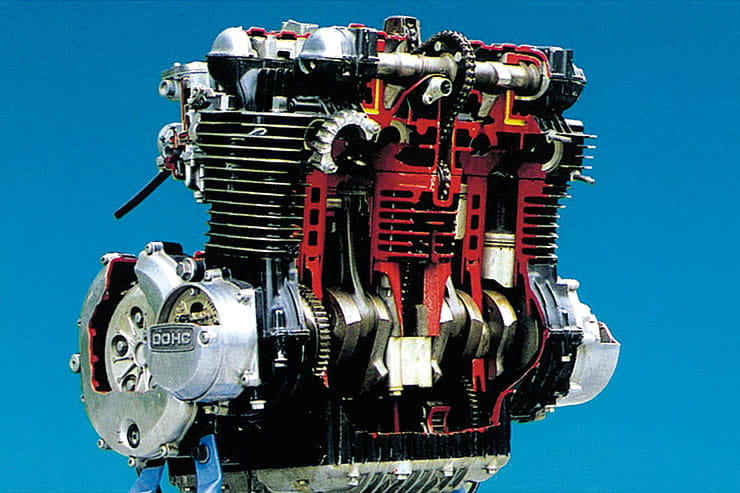

The basic story is fairly well-known. Kawasaki USA made a request to Japan for a new breed of superbike, dubbed 'Zapper' back in 1968. But Kawasaki Heavy Industries was already working on something that might suit: an inline-four, DOHC 750cc air-cooled engine had been proposed in 1967, under the code name 'N600'. Back then, the only real four-cylinder bike available was the super exotic MV Agusta 600, and while the new Kawasaki wasn't a copy, the DOHC layout and air-cooling fins gave a superficial similarity.

The new Kawasaki superbike project was going well, but in 1969, the project was rocked by some shocking news. Honda had launched its own 750cc machine – the CB750. It revolutionised the bike world straight from the off, and Kawasaki was left back in second place even before it started. This wouldn't do – at all.

The firm went back to the drawing board, and this is where Martin Lambert's research really provides some shocks. He discovered planning documents prepared by engineers at KHI in Japan, which examined a variety of larger engine layouts, from 800cc right up to a staggering 1200cc 120bhp monster. In the end, the firm went for a conservative 903cc 81bhp design – but it's incredible to think what might have been had it gone for that nuclear option. A 120bhp 1200cc superbike back in 1972? Insane!

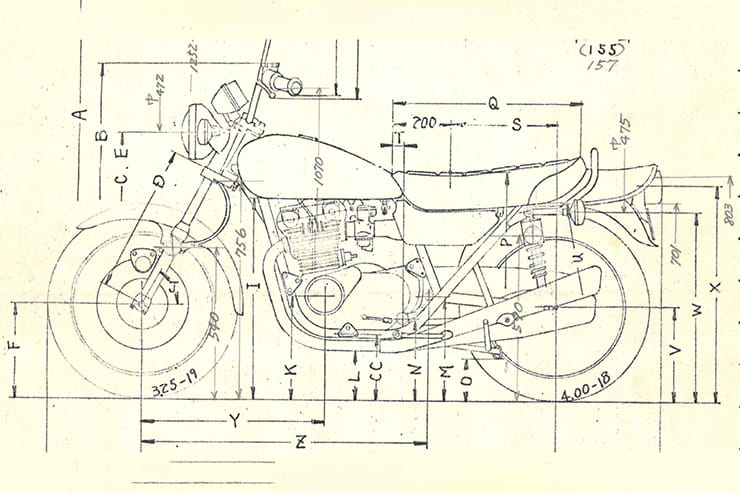

By now, the project had been renamed, from N600 to T103, and a series of prototype pics have been unearthed by Lambert from the Japanese archives. These show a range of styling options masterminded by Z1 designer Norimasa 'Ken' Tada: some with '749' graphics to throw any unauthorised eyes off the scent. They also show the fairly basic development chassis, using parts borrowed from the H1 and H2 two-stroke triple production machines from the time. The engineers at the time weren't really worried about the chassis design: they were sure they could manage that well enough, so most of the development work went solely into the engine.

Once the prototypes were almost finalised, Kawasaki came up with a pretty wild road-testing program. Sure, the firm ran bikes on its own test track at the Akashi factory, riding bikes right through the middle of the production facilities. It also ran road tests in Yatabe, north of Tokyo. But most audaciously, it sent two pre-production Z1s, with Kawasaki engineers as riders, to ride across the USA from coast to coast. Resources were tight: the team had one pickup truck as backup, and the test engineers would ride all day, then strip the motors down at night, measuring any wear and checking for any fatigue or breakage on internal parts. Martin Lambert actually showed us a photo of a Z1 engine being stripped down on a piece of matting by the side of the road for checking: this really was 'get your hands dirty' development engineering.

Mad as it sounds, this isn't even the wildest yarn Lambert had about the Z1 development rides in the US. Paul Smart, legendary Brit racer, was riding for Kawasaki at the time, and he was drafted in to help out with the testing. He too had a Z1 to ride across the states on – but his was disguised as a Honda CB750, complete with matching paint schemes and Honda badges. Only the obviously-different DOHC engine marked it out as a fake, and according to Lambert, only one person spotted the fake CB750 at a gas station stop one day. Even more incredible is the claim that Paul Smart actually entered his Z1 test mule into a local club race in the states, without anyone at Kawasaki knowing what he was up to. And, according to legend, he won the race easily and had to scarper before anyone spotted what was going on. You'd maybe take this story with a pinch of salt – if it wasn't for the photo of Smart with a pair of 'Honda' badged DOHC superbikes in a racetrack pitlane which Lambert showed in his presentation.

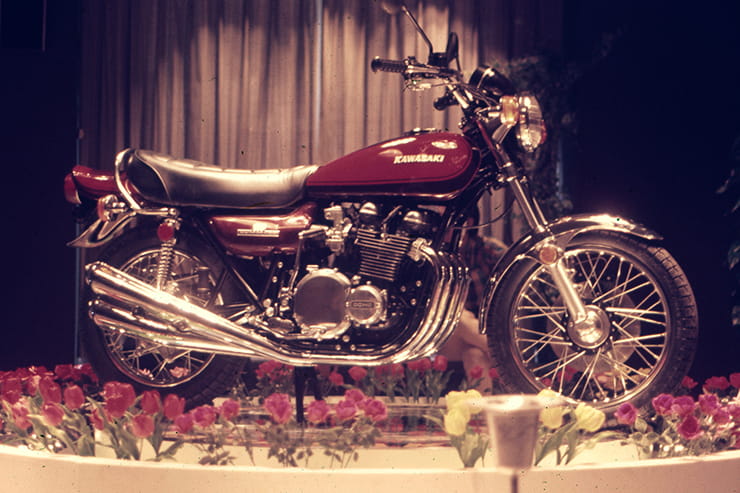

Near-mythical tales like this aside, the Z1 was a massive hit for Kawasaki. It was initially ridden by four editors from the big American motorcycle magazines, who, bizarrely, had to pay for their own flights to Japan in 1972. There was some talk of them all getting the first four production bikes to take home, with special gold ignition keys, but that ended up not happening. None of that mattered though: the Z1 easily topped the CB750 in terms of pure performance, and it finalised the blueprint for big-bore Japanese machinery for the next decade and a half. Bikes using inline-four, DOHC, air-cooled eight-valve engines, in a steel tube cradle frame, became so popular they were known as UJM – Universal Japanese Motorcycles, and all the Japanese firms would build them, some with more success than others. The Suzuki GS range did well, while Yamaha's XS bikes were less successful, and Honda had problems with its later CB750 and 900 developments, before wandering off down the V-four route with the VF models.

Kawasaki kept the faith though, and would hugely expand the Z range all through the 1970s: the Z1 grew in capacity to a full 1,015cc in the Z1000 and Z1-R in 1977-78, and then a beefy 1,089cc in the GPz1100 of 1981. An all-new upper-middleweight version of the Z1 motor appeared in 1976, the 652cc Z650, which would later grow to 738cc in the GPz750 and 750 Turbo. And rounding off the four-cylinder Z models was the 1979 Z500, that Kawasaki used as a base for the 1982 GPz550, arguably the true ancestor of the wildly-popular 600 supersports class from 1985-on.

The Z name found itself on both smaller and much bigger machinery too. Kawasaki America was very keen on having a sub-500cc machine, leading to the Z400 twin in 1974. A Z200 single appeared as a superlight entry machine, but then at the other end of the scale, Kawasaki came out with an absolute monster: the 1979 Z1300. A 1,286cc water-cooled inline-six engine made a claimed 120bhp with three dual-barrel carbs (it later switched to fuel injection) and used shaft final drive. It was a total beast of a machine – but let down by its enormous mass: around 320kg dry…

The Z range fell away in the 1980s. The next revolution in bike design from Japan brought water-cooling, full fairings, twin-beam aluminium frames, and much more performance. The Z bikes were usurped by water-cooled GPZs, ZXRs, ZX and ZZ-R machinery, all of which kept Kawasaki at the forefront of performance bike design for the rest of the century. The naked bike class became a niche sector, and while Kawasaki used the old Z technology as a foundation for bikes like the Zephyr range and the ZR-7, it looked like the Z moniker would gradually fade into history.

But the early part of the 21st century brought back a new interest in naked machinery. The likes of Suzuki's 600 and 1200 Bandit and the Honda 600 and 900 Hornet had shown the demand for simple, unfaired roadsters – so Kawasaki revived the Z1000 and Z750 names for two new water-cooled naked bikes in 2003/4. Since then, the class has gone from strength to strength, and Kawasaki has built Z models across all capacities: Z125, 250, 300, 400, 650, 800, 900, 1000, and the wild H2 supercharged version. The Z brand is definitely back, and has outlived all its usurpers.

So, will a journalist like me be writing about the 100th anniversary of Z in 2072, looking fondly at that immaculate GT750 in a Swiss vault and waxing lyrical about the current Z-E flying electric hyperbike, while munching on a 3D-printed Toblerone? I'd really like to think so…