We’ve already brought you all the details of next year’s enlarged CRF1100L Africa Twin long before you’re supposed to know them but a new patent application from Honda shows the firm is already working on even more significant developments for the bike and its parallel twin engine.

Next year’s bike is known to be getting an 86cc capacity hike to 1084cc, bringing 7hp with it for a peak of 101bhp, but we’re not expecting Honda to significantly change the basic makeup of the parallel twin engine that’s currently unique to the Africa Twin. That means the 2020 model is likely to stick with the existing cylinder head design, with a single overhead ‘Unicam’ camshaft and indirect fuel injection.

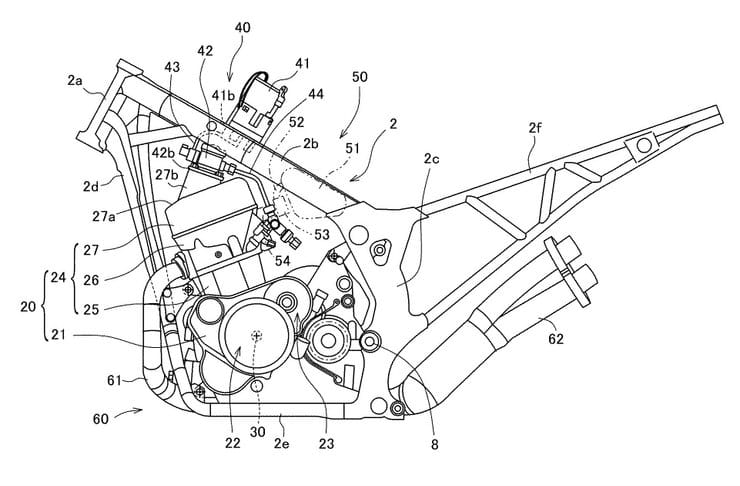

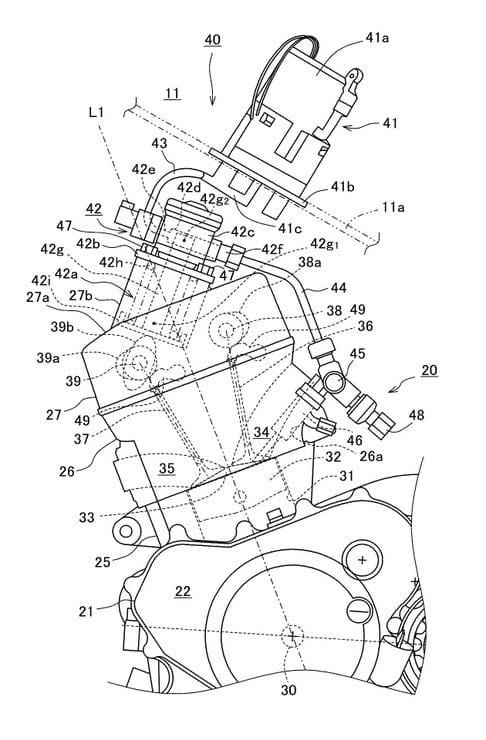

However, this new patent (above) shows a much more radically-altered version of the engine, with a new double overhead cam cylinder head and, most notably, direct fuel injection. That means the fuel injectors fire straight into the combustion chamber rather than into the intake ports.

Direct injection (DI) is something of a holy grail when it comes to beating emissions limits, but so far it’s proved hard to adapt to motorcycles. The American Motus V4 was originally intended to use the technology, but reverted to port fuel injection for the production version, and the idea of direct injection is also inevitably linked to the ill-fated Bimota VDue. In that machine it was supposed to end the issue of two-stroke emissions problems, but instead the bike was plagued with unreliability and rarely ran properly.

However, DI is now a well-established technology in cars and it’s likely to make the leap to two wheels sooner or later. Its advantage over conventional port or throttle body fuel injection is that it separates the functions of drawing air into the engine via the inlet valve and the injection of fuel.

With indirect injection the fuel and air are mixed as they enter the cylinder. That’s good when it comes to ensuring the fuel is properly atomised and able to ignite properly when the spark plug fires, but bad for emissions since most engines feature ‘valve overlap’ where the exhaust valve still hasn’t closed when the intake valve opens. Overlap is needed to properly fill the cylinder with air/fuel mix, particularly at high revs, but it means there’s an opportunity for unburnt fuel to escape through the exhaust, with bad results for emissions.

Direct injection can solve that problem because it means the air and fuel are kept separate until the last possible moment. With nothing but fresh air entering through the inlet valve, having lots of valve overlap doesn’t matter. Direct injection means the fuel can be added later, after the exhaust valve has closed, to prevent unburnt fuel escaping into the exhaust.

So why aren’t we using it already? It’s because the technology is particularly hard to combine with the sort of high-revving engines bikes tend to use.

The problem is that by adding fuel so late in the engine’s cycle there’s very little time for it to atomise and mix properly with the air in the cylinder, and on a high-revving bike engine that’s a particular problem. The inability to get a proper air-fuel mix is one reason the Bimota VDue struggled.

To aid fuel atomisation, DI requires a very high-pressure fuel pump. That’s one of the key elements visible in the new Honda patent. As well as a normal electric fuel pump (numbered 41 in the patent pictures) it needs a high-pressure, mechanical fuel pump (42). This is mounted on top of the cylinder head and driven by the exhaust camshaft. High-pressure fuel then runs to a fuel rail (45) between the injectors (46), which are electronically instructed when to add fuel to the cylinders.

Since the days of the Bimota VDue, DI technology has come a long way, with injectors and pumps that far improve atomisation. In recent years the tech has improved to the point where it’s increasingly common on production cars including high-performance models like the BMW M5 and Chevrolet Corvette, and even the latest generation of F1 cars – which are capable of bike-like high revs – use direct injection.

While there’s a possibility that this direct-injected engine will appear on next year’s revamped Africa Twin, it’s not been mentioned in any of the documents we’ve seen or the rumours we’ve heard. As such, it’s likely this patent refers to a development that’s further in the future. We’ve already heard that Honda is planning to expand the Africa Twin range, adding a smaller version – perhaps around 850cc – to the range after the introduction of next year’s enlarged CRF1100L version.

It’s also clear that, as Honda’s best-selling large-capacity bike, we should expect the Africa Twin to get the sort of regular, significant model updates that used to be associated with superbikes and supersports machines. Before falling from favour with buyers, Japanese 1000cc and 600cc sports bikes were routinely revamped every two years, with major updates every four. Honda appears to be taking a similar route with the Africa Twin, which first came as a 2016 model, was updated for 2018 and is getting a major change and the 1084cc capacity for 2020.

So even if next year’s Africa Twin doesn’t get direct injection, it’s quite possible that the engine seen in this patent will be adopted at the next update, presumably for the 2022 model year.