Author: Frank Melling Posted: 05 Sep 2014

Last week Bruce Anstey raced an ex-factory Yamaha YZR500 Grand Prix bike around the 37.73 Isle of Man mountain course to take victory in the Motorsport Merchandise Formula 1 Classic TT from Michael Dunlop on an old four stroke XR69 Team Classic Suzuki. It was over ten years ago that 500cc two strokes were replaced by the four stroke Grand Prix machines similar to those we see today. We thought we’d delve into the history of the 500cc two-stroke to celebrate Anstey’s remarkable win.

The Unrideables. Death on wheels. The biggest, baddest, most evil racing motorcycles ever to see a race track. The 500cc two strokes are the bikes which dominated motorcycle racing for almost three decades.

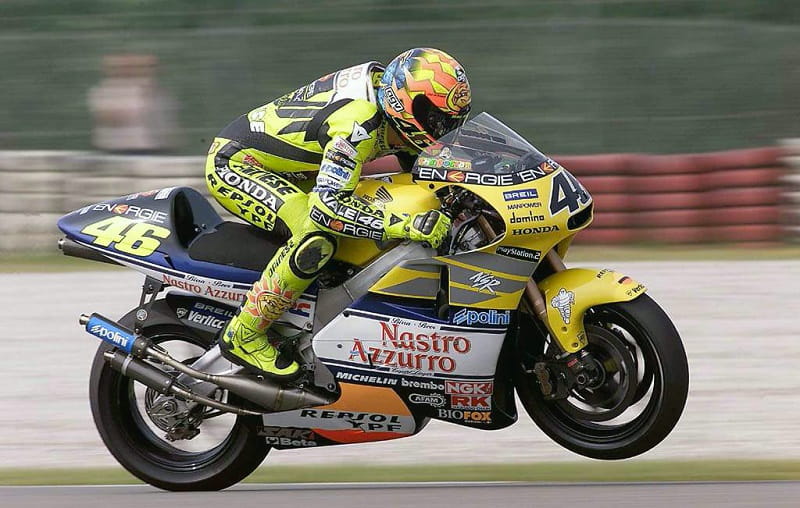

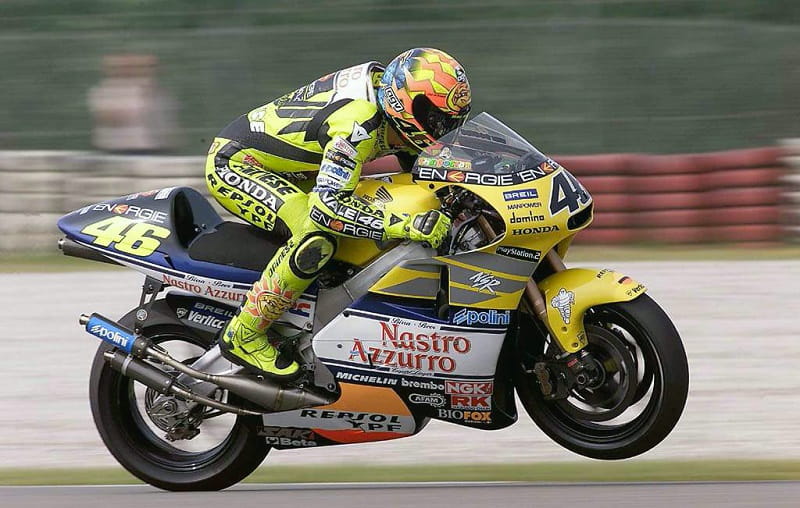

The numbers do not do justice to how fast these bikes were. At the end of almost three decades of GP racing Honda produced a bike weighing only 130kgs (286lbs) but with almost 200hp. Valentino Rossi won the last 500cc World Championship for Honda in 2001 but settled for a bike producing a mere 168hp, and a 200mph top speed, because 200hp was too much even for the ultimate Moto God.

The birth place of these monsters was not, as you might think, the motorcycle race paddock but the top secret Peenemunde German rocket research centre during the Second World War. It was here that the talented engineer Walther Kaaden learned how individual molecules of gas behaved under extreme pressures and temperatures.

After the war, Kaaden became the Chief Engineer at the East German MZ factory and it was his work in the 1960s which provided the foundations for every two-stroke race engine - even today.

After the war, Kaaden became the Chief Engineer at the East German MZ factory and it was his work in the 1960s which provided the foundations for every two-stroke race engine - even today.

Right up until the start of the 1970s, four strokes dominated the 500cc class in motorcycle racing. It was considered technically impossible to ever make a reliable 500cc two-stroke racer. The man who changed that perception forever was Barry Sheene - along with British frame builder Colin Seeley.

Barry’s Dad, Franco, obtained the engine from a fast, but incredibly bad handling, factory TR500 Suzuki and took the air cooled twin to Seeley to make a bike which handled as well as the old fashioned Matchless and Norton singles but which would run with the two-stroke Kawasaki triples which were starting to appear in GPs.

Seeley succeeded and the new bike proved that Sheene could ride big bikes, in motorcycling’s Premier division, just as well as he could the 125s on which he made his name.

Good as the Suzuki TR500 engine was, and at the end of its life the best motors gave over 70hp, it was always a converted road engine which was never intended for racing. What was needed was a true, purpose built GP bike.

In fact, Suzuki were beaten to the punch by Yamaha who cleverly used their experience with 250cc twin cylinder racers to produce a 500cc, four cylinder bike which took GP legend Giacomo Agostini to his last World Championship in 1975. It’s a common misconception to think that the OW23 was simply a pair of 250s joined together because the four cylinder 500cc engine is unique but for sure Yamaha took an immense amount of knowledge from their twins.

By contrast, Suzuki started with a blank sheet of paper and produced a four cylinder, disc valved engine in a square configuration. The factory had experience of this design from their 250cc GP bike – fondly known as “Whispering Death” because of its fondness for seizing and hurting riders! The new “Square Four” became known as the legendary RG500 and gave Sheene two World Championships in 1976 and 1977. By now, the two-strokes were producing over 100hp at the back wheel and were good for 175mph!

Yamaha hit back with a series of ever improving OW models plus the abrasive, but super talented, Kenny Roberts who took the title in 1978, 1979 and 1980. Now, 130hp was standard for any decent 500.

At the time, Honda was known first, last and middle as a four-stroke company. It was they who made the legendary five cylinder 125cc and six cylinder 250cc bikes which had dominated GPs in the 1960s.

Even in the height of the two-stroke era, Honda remained a four-stroke company and so went racing with the eight valve, oval pistoned NR500 which was the most sophisticated GP motorcycle of its day – but one which still couldn’t get near the performance of a two-stroke Yamaha or Suzuki.

In 1982, Honda admitted the reality of the situation and produced their own two-stroke - but one which was radically different from the machines raced by Yamaha and Suzuki. The team was led by Mr. Oguma, who was a motocross engineer, and he was prepared to lose outright power to make a bike that, motocross style, was light and slim. The result was the legendary NS 500 triple which had two vertical cylinders and one horizontal. Although down on horsepower, when compared with both Suzuki and Yamaha, the Honda was easy to ride and handled superbly. It was this bike which took Freddie Spencer to two World Championships.

Good as the triple was, it could never compete on power and in the two-stroke war the ultimate weapon was a V4. This configuration gave the best possible combination of handling and power, and saw Honda and Yamaha battle it out through the 1980s with bikes which produced insane amounts of power for minimal weight.

Suzuki were still in the war, and Kevin Schwantz wheelied and slid his RGV to the 1993 title, but it was Honda, their V4 and Mick Doohan who ruled the late 1990s with five consecutive titles – and a string of major injuries for the heroic Australian.

For many racing aficionados, Doohan’s victories were the most dramatic of the whole two-stroke era. Good as his NSR Hondas were, the bikes were vicious, violent, tyre shredding animals which took not only a huge amount of riding skill to race but cojones the size of a fit Hereford bull. You either conquered these bikes or they broke your body. There was no middle ground!

Suzuki still battled back with another update of the RGV. Kenny Roberts Junior earned a well-deserved victory on the Suzuki in 2000, over the up and coming young Valentino Rossi who had just made the move to the 500cc class.

Once Vale had worked out how to race the NSR, as distinct from just surviving on it, the precocious young Italian owned the class right up until the inception of MotoGP in 2002.

And now for the big question. Speak to Kevin Schwantz, Mick Doohan or even Vale and they will tell you the same thing. Even with half the capacity of the current four-stroke MotoGP machines, if you ran a two-stroke today with the benefit of latest electronics and plenty of fuel capacity then this would be the machine to beat.

So, maybe GP development reached its apogee in 2001 and it is regulations which have been driving back progress ever since. What do you think?

or !

After the war, Kaaden became the Chief Engineer at the East German MZ factory and it was his work in the 1960s which provided the foundations for every two-stroke race engine - even today.

After the war, Kaaden became the Chief Engineer at the East German MZ factory and it was his work in the 1960s which provided the foundations for every two-stroke race engine - even today.