The name ‘Hayabusa’ didn’t exactly get the blood pumping when we first heard it back in 1998. But a few months later in 1999 when the world’s fastest production bike hit showrooms it instantly became one of the most famous badges in motorcycling history.

Such is the legend that’s grown around the ’Busa since it first appeared, the ever-present rumours that Suzuki is to relaunch the title on an all-new world beater are mouth-watering even in a world where the prospect of ever hitting its near-200mph top speed is vanishingly small.

The Hayabusa nametag, which seemed a bit odd at its launch, has become just as entwined with motorcycling history as terms like Katana or Ninja. It’s the Japanese term for the peregrine falcon, ostensibly because that’s the world’s fastest bird, capable of more than 200mph. No doubt it wasn’t lost on Suzuki’s marketeers that the peregrine falcon also tends to feed on smaller, slower fliers. Blackbirds, for example…

It’s hard to believe that a full two decades have passed since the Hayabusa first redefined the concept of what ‘fast’ meant on a motorcycle. Familiarity with the bike – its shape and much of its technology has barely changed since it was launched – means you’re unlikely to look twice if one rides past today, but back in the days when we were worrying about the Millennium Bug and a Nokia 3210 was at the cutting edge of mobile phone technology, the Hayabusa might have come from another planet.

Is it all about speed?

Before we go into what really made the Hayabusa remarkable, let’s deal with the whole top speed question. Every bike magazine rushed to speed-test the bike the moment they could get their hands on one, with the prospect of the Suzuki being the first stock production machine to legitimately break the 200mph barrier looming large. But it never did; back in the day, around 194 was the highest speed independently tested for a stock Hayabusa. Not that it matters because at those speeds even tiny differences in conditions – wind speed, air pressure, altitude, humidity – can have a noticeable impact on results.

Instead of focussing on the pointless 200mph number, the way to really understand the Hayabusa’s impact is to look at its period rivals. At the time, a Kawasaki ZZR1100 could manage somewhere in the 170s and a Honda CBR1100XX Super Blackbird could just about knock on the door of 180mph. And while today’s 1000cc superbikes can all happily hit their self-imposed 186mph top speed limit, in 1999 you’d be lucky to find one that could pass 165mph. Even the then-new Yamaha R1 could barely scrape to 170mph with a following wind. A Hayabusa could pass it going nearly 25mph faster…

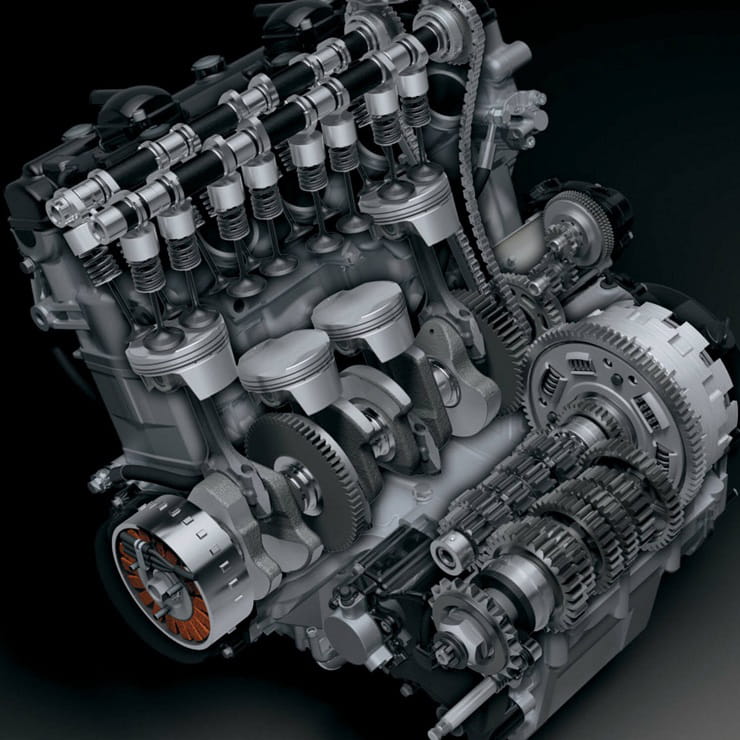

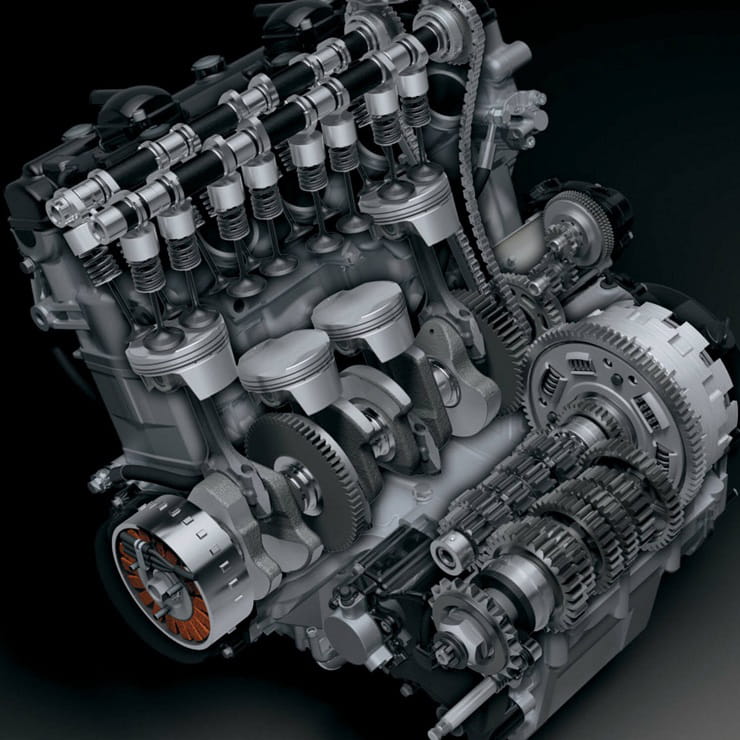

Nothing radical here, but the Hayabusa engine is immensely powerful and tuneable

A legendary engine

So how did Suzuki achieve such dominance over its rivals? The answer was a double hit of power and aerodynamics, with the original generation Hayabusa setting new standards on both fronts.

Power was an obvious starting point, and Suzuki followed a tried and tested means to get it: capacity. While its clearest rivals – the ZZR1100 and Blackbird – respectively had 1052cc and 1137cc engines making 145hp and 162hp, the Busa brought out the big guns with 1298cc and a claimed 175hp. It was a clean-sheet design, incorporating the latest thinking in terms of fuel injection and individual coil packs for each cylinder, putting it at least a generation ahead of the motors its rivals used. Allied to ram air, the result was a power level that was truly eye-opening at the end of the last century. Even today, when plenty of bikes can claim more horsepower at their high-revving peaks, a Hayabusa’s engine feels surprisingly muscular. While the bike’s power made headlines in its day, the Busa’s torque – 104lb-ft at just 7000rpm – embarrassed rivals at the time and even makes modern superbikes look limp; a Panigale V4 can manage 91.5lbft (the same as a 20-year-old Honda Blackbird) and needs 10,000rpm to get there.

Wind tunnel work was key to the Hayabusa’s development

Aerodynamics and handling

That engine would have been impressive regardless what bike it found itself in, but the Hayabusa’s aerodynamics were also vital to the big numbers that made it an instant legend.

Few people would ever call a Busa beautiful; the fairing’s odd lumps and curves allied to an over-tall seat hump, unfashionably long tail and a stacked headlight arrangement that was briefly in vogue at the time made for an unusual appearance. What might have been a weakness was turned into strength; the styling was instantly recognisable so you immediately knew when the world’s fastest production bike rode by.

Of course, the shape was dictated largely by the wind tunnel, and the knowledge that the Hayabusa looked the way it did for a reason, not just on a designer’s whim, made it much more acceptable. The fairing and enveloping front mudguard cut the air with unparalleled efficiency as the bulbous nose helped split it into the ram-air ducts forcing it into the ever-hungry engine. At the back, that exaggerated seat hump smoothed airflow off the rider’s back using lessons from Suzuki’s RGV500 GP bike.

While previous high-speed expresses happily sacrificed handling for straight-line stability and comfort, the Hayabusa made a far better fist of throwing handling into the mix. While it was never going to rival a race-bred superbike in corners, it felt much more agile and sporty than the likes of the ZZR1100 or Super Blackbird. In a modern context any Hayabusa is bound to feel like something of a truck – albeit a very fast one – compared to the latest superbikes, but in its day you’d find few criticisms of its handling or brakes. Combined with that friendly, torquey engine and spacious riding position, the result was a machine that devoured miles more effectively than almost anything else on the road, turning dreary commutes into brief blasts and longer trips into relatively painless experiences without the handling sacrifices associated with a dedicated touring bike.

Second-generation Hayabusa debuted in 2008

Development history

Most bikes with two decades of history under their belt will have undergone a multitude of updates and changes to keep them on the pace, so perhaps it’s a testament to the Hayabusa’s essential ‘rightness’ that it’s barely been altered other than one mid-life facelift.

There’s another reason for the lack of development, though. Just a year after the original 194mph version went on sale, the world’s bike firms hit upon the now-famous ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ not to pursue top speeds higher than 186mph (300km/h). That deal, struck shortly before the introduction of Kawasaki’s ZX-12R (which had previously promised to unseat the Hayabusa from enviable ‘world’s fastest’ spot) instantly took the fire out of a contest for speed-freak bikes. Potential rivals for the Hayabusa’s place were either redesigned with touring in mind – notably BMW’s K1200S, which had been conceived as a Busa competitor – or cancelled altogether like the near-mythical Triumph ‘A13HC’. Likely to have been called Hurricane had it reached production, that was a 1300cc four-cylinder with innovative aerodynamics (the all-enveloping front fender pivoted on the fairing and the suspension allowed the wheel to move vertically inside it), but Triumph canned the project at the last minute before its planned 2004 introduction.

Kawasaki’s ZX-12R was also short-lived, dropped in 2006, leaving the Hayabusa with the field for autobahn expresses virtually to itself and effectively removing the need to invest in the bike other than to keep pace with legislative changes.

As such, the alterations during the first-generation Busa’s life apart from regular colour changes were electronic tweaks in 2003.

The second-gen bike was introduced in 2008 with an updated 1340cc engine making a claimed 194hp, developed in response to then-new Euro 3 emissions rules. The brakes were improved with radial calipers and the suspension was uprated, while bodywork changes gave an even more bulbous style with an oddly droopy tail. Further tweaks five years later added ABS and Brembo calipers, but when Euro 4 emissions laws came into force in 2016 Suzuki opted not to bring the Hayabusa into line. Although European rules allowed the non-compliant bikes to be sold for another two years, it was finally forced from the market in 2018, although it remains on sale in the USA.

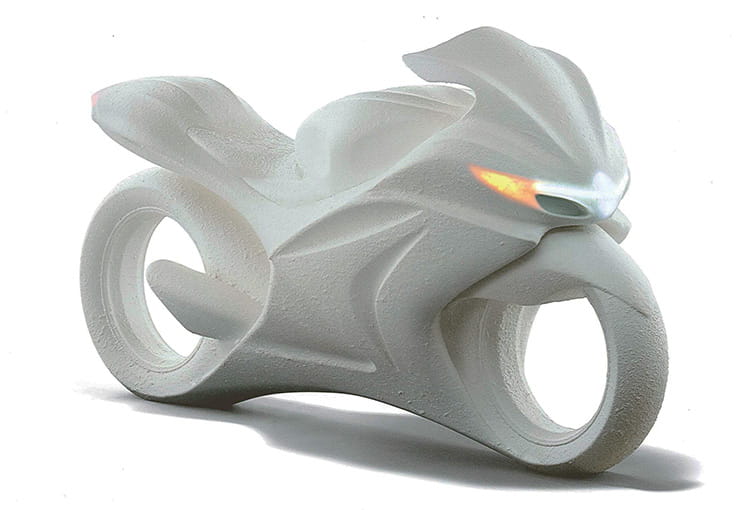

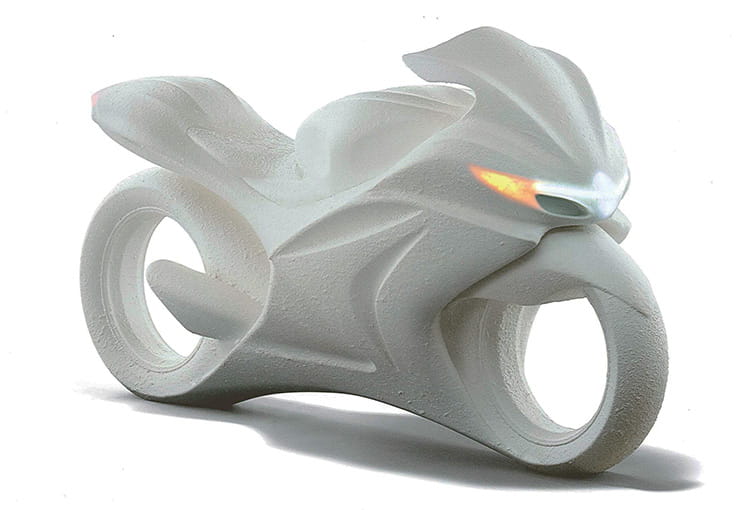

The 2015 Concept GSX previewed the style of a future Hayabusa

Hayabusa future

Suzuki has been teasing us with the prospect of a new Hayabusa for years, and while patents have regularly appeared showing that work on such a bike has been ongoing there’s still no official word on when we might see it.

The closest thing there’s been to an official confirmation of a new Hayabusa was Suzuki’s ‘Concept GSX’ shown in 2015, which clearly previewed the styling direction that a next-generation version is likely to take, carrying over key cues including twin raised ridges on the front fairing, a central headlight, side intakes flanked by moulded-in turn signals and an extended front mudguard.

Now, four years on from that concept’s appearance, we’re left wondering whether the real version of that bike is ever going to reach production.

Suzuki’s own GSXR/4 concept car showed the versatility of the Busa engine

Racing and tuning

Although never designed as a race bike, the Hayabusa quickly established itself as the machine of choice for many drag racers and even today it remains a dominant force in both drag racing and among land-speed record chasers. The Busa’s inline four has proved to be enormously tuneable, spawning ever-more-powerful turbo versions and even V8 derivatives.

The current world land speed record for motorcycles is still held by Ack Attack, a streamliner with two Hayabusa engines that managed 376mph back in 2010, and the Busa is a favourite in the cottage industry that’s built up around transplanting high performance motorcycle engines into cars. Even Suzuki got in on that game, showing the GSX-R/4 concept car in 2001 and the Hayabusa Sport concept in 2002, both track-oriented two-seater cars packing a stock Busa engine under the bonnet, and creating the one-make Formula Hayabusa single-seater race series.

The Hayabusa engine has also become the lynchpin of other one-make car race championships like the Radical SR1 Cup, as well as powering an endless stream of homebrewed hill-climbers and sprint cars.

Not since the early days of Formula 3, when the cars were powered by 500cc single-cylinder bike engines, has a motorcycle engine been so successful in making the transition to four-wheeled competition.

Even when Suzuki finally gets around to reviving the Hayabusa – and all indications are that it’s going to happen within the next couple of years – the new version will face a tough job filling the shoes of the machine that blew us all away back in 1999.