Date reviewed: September 2019 | Tested by: John Milbank | Price: £79.95 | fit2gotpms.com

Branded for Michelin, the Fit2Go Tyre Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS) on review here promises an accurate display of the pressure in the front and rear tyres of motorcycles, scooters, mopeds and all other two-wheel modes of transport.

Previously only found on top-of-the-range bikes with the sensors mounted to the inside of the wheels, this system transmits from the tyres’ valve caps to a small display that you can stick on the dash. I’ve been testing in on a Kawasaki Versys 1000 for around 500 miles…

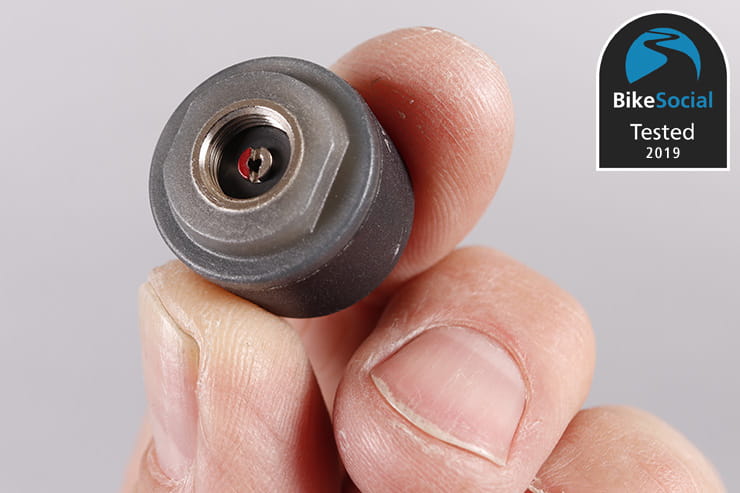

The pressure sensors replace the tyre’s original valve caps

How easy is it to fit?

The sensors are screwed directly to the valve stems; there’s also a pair of locking nuts supplied, along with a tool to nip them up (though you can use a standard spanner). It’s important here to point out that I wasn’t able to fit these to my BMW S1000XR as the front valve stem (which is fitted to the cast spokes) ends close to the caliper, resulting in the sensor hitting it with every revolution. There could also be a clearance issue on other bikes with right-angle valve stems, but if you’re in any doubt you can contact Fit2Go to request a free dummy sensor, which you can try on your bike.

While the lock nuts are said to be optional, I used them as I didn’t want there to be any chance of the sensors loosening off – there’s a point when they’re removed at which they’ll hold the valve open but not fully seal, allowing air to escape.

The display unit is held magnetically in a simple cup that sticks on your bike. I found a spot on the left of the fairing that took it, but do note that the magnet isn’t hugely powerful. Having read some online reviews that complained of the display falling out on the road, I wanted to make sure mine would stay in place. I’ve since deliberately hit potholes and speed bumps at a good pace, as well as bumped over kerbs, and never had it shift. I’d suggest you keep it as horizontal as possible, though it would have been nice to have a more secure locking system – perhaps seeing the display twist to lock.

That’s all there is to fitting– you’re told to ensure the tyres are at the correct pressure before popping the sensors on (using a separate gauge), and within a couple of minutes of riding the display alternates between front and rear pressures. After that, I’ve found it comes on almost immediately after moving the bike. And checked against my high-quality handheld gauge, it’s very accurate.

The display unit is very compact, and easily charged using the supplied inductive charger

How clear is the display?

In bright sunlight the display isn’t that clear – it takes a good look to check it. As the ambient light reduces it gets easier to read, but not to the extent that it dazzles at night. It’d be good to see the brightness increase during the day – though this would reduce battery life – or to have a clearer screen design (maybe a standard LCD?).

When the pressure drops by 15% or more the display flashes, along with a white LED in the bottom of the unit. But it’s not very bright; in daylight especially, this will be unlikely to get noticed quickly unless it’s mounted directly in your eyeline.

You can switch between Bar and PSI for your preferred pressure measurement.

While it looks worse in these pictures, the display is still a little hard to read in sunlight

Do they make it harder to pump the tyres up?

Without the lock nut, it’s no more hassle to remove the sensor and pump up the tyre than it is to take the original filler cap off. When you put the sensor back the device assumes that the pressure in the tyres is 100% (so it knows when to alert you to a percentage change), so there’s nothing else to do. Of course, as you ride the temperature will increase and you’ll see the pressures rise; just remember that bike (and car) tyre pressures must be set when cold!

With the locknuts fitted, you need the tool or a spanner to get the caps off, and on the Versys at least, you also need to spin the nut off to get the pump on. It does add an extra step of hassle, and I’ll admit I’ve delayed pumping my tyres up (they naturally lose pressure over time), but having said that I probably wouldn’t have checked them again within that time if I didn’t have the TPMS.

The display and sensors are of course completely waterproof, so you don’t need to worry about rain or washing. The threads of the sensor caps are nickel-plated, which should mean they resist corrosion but Fit2Go advises that you check them every so often, especially if riding through winter.

The sensors fit on most bikes, but not all

How long do the batteries last?

The display is claimed to last up to three months, depending on usage. It goes to sleep automatically, but I’ve used the bike every day and been moving it around a lot when it’s not in use. The unit has been fitted for all that time and hasn’t dropped a bar on the power display in a full month; I’ve no doubt that it will easily last the quoted three months before needing to be charged, which is a simple job of popping it into the supplied inductive USB-powered charger.

The long life of the display battery is another reason I’d have preferred to see a more secure mounting system; maybe even one with a simple key so you’re not worried about taking it out every time if you’re worried about it being stolen.

The valve cap sensors each have their own cell inside, which can’t be charged or replaced; the quoted life of these is three to five years, but replacement sensors are said to be shortly available from Fit2Go.

The supplied tool can be tucked under your seat to remove the optional lock nuts

Are the sensors safe on rubber valve stems?

Incredibly, despite having a battery, accelerometer, pressure sensor and transmitter inside the valve caps, they weigh just 8g. Fit2Go says that they should be used on tyres with metal valve stems, but that they’re also fine when used on ‘good quality’ rubber valve stems. That means that they’re not worn or cracked, but the short answer is yes, they are safe. For a longer, and much more geeky answer, see below…

One BikeSocial Test Team member’s valve stem did fail…

If you are using them on rubber valves you should ensure that they’re replaced at every tyre change. BikeSocial Test Team member Man Tas suffered a split valve stem on his 2015 Yamaha MT09 Tracer; it had covered 23,000 miles, but not had the valves replaced at least on the last tyre change. He tells us that the stem tore a little under two months after installing the caps; “I should have replaced the valves when changing the tyres, right before installing Michelin TPMS, but I forgot. The worst part was that the display unit’s battery went flat an hour before!” While typically the system would warn the rider of the drop in pressure, in this case it came down to feel.

Ultimately, metal valve stems are the safest bet, and Man Tas has since fitted them to his bike, but if you’re using rubber, make sure they’re replaced with the tyres and that you keep an eye on them.

If the pressure changes significantly, the unit warns you with a flashing white LED

Is the Fit2Go TPMS worth buying?

Fit2Go says that its system could warn you of an impending blowout, either through a drop in pressure, or an increase due to extra heat (it’ll also warn you if the pressure increases above 35%, or if the pressure is dropping faster than 2psi per minute). I think it’s pretty unlikely you’d notice it flashing in time – having suffered a blowout on a Kawasaki Z1000SX a few years ago, I know that the time between the damage occurring and the carcass failing was very short. Add the fact that at the time I was watching the road as I overtook several cars and I’m not sure the TPMS would have warned me.

But that doesn’t mean I’m unimpressed – I now check my tyres at the start of every ride, and glance at the display every so often while I’m out. I know my tyres are okay.

We’ve all had those moments that you doubt your tyres – maybe a short slide or a loose stone that just knocks you off line; a quick glance at the TPMS display can reassure you that your pressures are okay, and allow you to relax back into the ride.

£79.99 isn’t cheap, but this really is a superb safety item – however often you ride, it’s worth the investment.

Bennetts customers can save 10% on this and the Fit2Go Tyre Pressure Checker, exclusively at Bennetts Rewards.

*Rubber valve stems… The geeky answer

The first thing I wondered when I saw this system was what effect the sensors would have on the valve stems; at speed, could they cause damage? 8g might not be much, but the original valve caps weigh less than a gram.

Using an online centripetal force calculator, I worked out that, given the sensor is 175mm from the centre of the Versys’ front wheel and that the tyre has a 300mm rolling radius, at 70mph the force acting on the valve stem is 15.23 Newtons, or 1.55kg.

At 100mph that force increases to 31.09 Newtons, or 3.17kg. Jump to 150mph and the force reaches 69.94 Newtons – 7.13kg. That’s a massive increase over the standard valve cap – at 150mph, if it weighed 1g it’d only be putting 0.89kg of force down (8.74N).

Is that bad? On my Versys 1000 the valve stems seem fine with that pressure acting directly down on them, but I asked my brother-in-law – an engineer and scientist so clever that it makes me think my wife must have been adopted – what he thought…

“The force acting on the valve stem will be directly down, assuming it’s in a vacuum.” He told me. “With wind, the big problem is oscillations – it’s effectively a big mass on a really under-damped spring. The back and forth oscillations could easily produce many times more force than the centripetal force, especially if there are any resonant frequencies.

“But we only need to care if there’s a resonant frequency that might be stimulated when the wheel rotates. At 100mph, the input is 23.6Hz, so the resonant frequencies we need to worry about at that speed occur at the first, second and third harmonics; 23.6Hz, 47.2Hz and 70.7Hz.

“Pushing speeds higher, in case you’re on a MotoGP bike or something, would increase those dangerous frequencies. Basically, at 186mph, the third harmonic would be 131Hz, so anything below that would be bad.

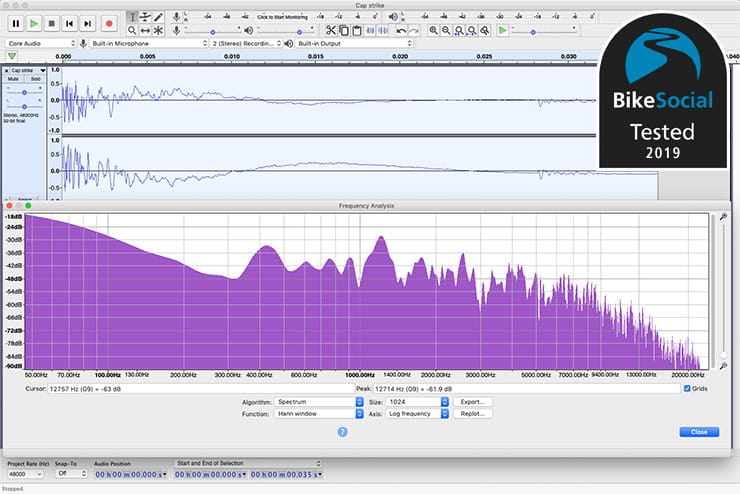

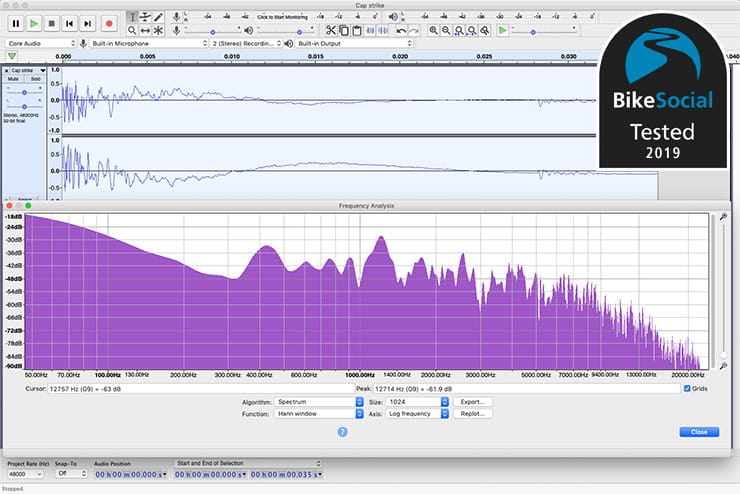

“Now, assuming a valve stem of 35mm, the resonant frequency would be hit at 70.4mph if it was infinitely floppy. But it’s not – I’d estimate the resonant frequency to be at least three or four times that, but we can check it by hitting it with something hard, recording the sound then looking at the trace using Fast Fourier Transform in Audacity.”

I thought he meant it was okay to not worry about resonant frequencies (all this was being done over WhatsApp as he lives in Italy), but after a lot of Googling I worked out how to view an FFT trace in Audacity, so recorded it using a Zoom H5 and this is what I got…

It didn’t mean much to me, but I also looked at the trace of the audio without the strike, and that big lump at the start wasn’t there… maybe I only needed to worry about the first big spike? “That big lump on the left of the plot (or rather the lack of a lump on the right) is due to the filters in your microphone,” he patiently explained to me. “It’s a low-pass filter – if you’re a nerd you can estimate the weight of all the microphone components from it.”

That first peak occurs at 423Hz, which is well past the third harmonic even at 186mph. So all we need to worry about is the centripetal force acting straight down onto the valve stem. The geeky answer is that they’re safe, as long as the rubber valve stems are in good condition.

But what about the fourth harmonic? “As a general rule of thumb the fourth harmonic doesn’t matter,” he said. “Though if you’re designing a helicopter you’d still care.”

You have successfully signed up.