It only seems a moment ago that bike firms were thrown into turmoil by the demand to meet stringent ‘Euro 4’ emissions laws. That rule-change led to famous models being discontinued and new technologies like ride-by-wire exploding across the market but it’s already nearing the end of its life. Its replacement – Euro 5 – starts to be phased in on 1st January 2020.

The new rules actually stem from the same piece of legislation that introduced Euro 4; the snappily-titled Regulation (EU) No 168/2013 on the approval and market surveillance of two- or three-wheel vehicles and quadricycles. Passed into law in early 2013, it set out a staged route to reduce bike emissions over a period of years. In January 2016, Euro 4 rules were applied to all newly-homologated motorcycles. In January 2017 the same rules were applied to existing models – although bike firms have managed to use so-called ‘derogation’ to gain an additional two years of grace to continue to sell small numbers of Euro 3-spec bikes right to the end of 2018.

While the last of those old Euro 3 machines have only recently been withdrawn from sale in the European market, Euro 5 means we can expect another imminent cull and extensive redesigns as current Euro 4-legal models are revamped or replaced to suit the new limits.

You might think that a piece of EU legislation is relevant only on that continent, but European emission rules are fast becoming the closest thing we have to a worldwide standard. Massive international bike markets including India and China also base their legislation on Europe’s emissions limits, and Japan also aligned itself with Euro 4 back in 2017.

Even America, which has its own emissions laws and limits, is affected because bike firms design their machines with the EU standards in mind and then modify them, where necessary, to suit the US rules.

Global engineering firm Ricardo might not be a name that’s familiar to all, but in the automotive and motorcycle industries it’s the company that others turn to when they need engineering help. Confidentiality means Ricardo’s client base is largely secret but projects in recent years include the development of BMW’s K1600 six-cylinder motor and Norton’s new 1200cc V4 superbike engine, while on four wheels you’ll find Ricardo’s fingerprints on supercars from McLaren and Bugatti.

We spoke to Paul Etheridge, head of strategy and business development at Ricardo Motorcycle, and Michael Ryland, who’s the firm’s technical lead on motorcycle emissions, looking after its Euro 5 programmes, to understand how the new rules will affect bikes in 2020 and beyond. As well as being experts in engine design, both men are keen riders; Michael Ryland rides a Triumph Street Triple and Paul Etheridge’s collection includes an original Suzuki Hayabusa, an Indian Chief Vintage, a Yamaha XV1700 Warrior, a Suzuki GT750A and a Honda CB750K6.

While Euro 5 may be new to most of us, it’s something Ricardo has been working towards for a long time. Paul Etheridge said: “We've been living with it for years! It's quite interesting how different customers have approached it in terms of seriousness and timing. We've done several Euro 5 projects for various customers around the world. The first we started in 2013, for a company that was quite forward-thinking and wanted to understand the implications from a very early stage so they could gear up properly for it, while other companies we're just starting work on it for. Some people lead from the front, some people panic at the last minute…”

How is Euro 5 different?

Michael Ryland explained how the Euro 5 standards have changed: “Compared to Euro 4, the emissions limits are much lower, so it's a considerable challenge for the manufacturers both in terms of meeting the legislation - and particular motorcycles have particular issues with it, some are easier than others - and also meeting it at a reasonable cost.

“The limits have gone down by about a third on average. It's different for each emissions type. It's not as big a jump as Euro 3 to Euro 4, however as you decrease these limits it just gets tougher and tougher to meet them as you run out of quick hits for reducing your emissions. So it gets more and more expensive.”

Currently, Euro 4 limits place restrictions on the amount of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). As well as reducing those totals, Euro 5 adds a limit on the amount of non-methane hydrocarbons in the exhaust, and that’s proving to be a particular challenge for engine designers.

Michael Ryland said: “Hydrocarbons are basically unburnt fuel that's not been able to fully combust in the chamber, or burn off in the exhaust or catalyst, and non-methane hydrocarbons are simply the ones that aren't methane. The EU has an assumption that non-methane hydrocarbons make up about 68% of your total hydrocarbons. But in reality, on most engines, non-methane hydrocarbons make up more like 90% of the total. The real challenge is being able to reduce the emissions for non-methane hydrocarbons without increasing your NOx, because one wants the catalyst to be rich and the other wants the catalyst to be running lean, so you have to balance it very carefully as close as you can to stoichiometric conditions in all transient operation across the test cycle.”

|

|

Carbon monoxide (mg/km)

|

Total hydrocarbons (mg/km)

|

Non-methane hydrocarbons (mg/km)

|

NOx (mg/km)

|

|

Euro 4 Limits

|

1140

|

170

|

Not legislated

|

90

|

|

Euro 5 Limits

|

1000

|

100

|

68

|

60

|

Compared to relatively low-revving cars, bike engines – and high-revving sports bike engines in particular – have problem when it comes to hydrocarbons. As Michael Ryland explains: “On higher-performance engines you typically have longer valve durations which causes many issues, in particular for the hydrocarbon emissions. It means your exhaust valve is probably opening quite early, which is great for power as it means it's easier to get the exhaust gasses out, however for emissions it means the combustion process is only partially complete by the time the exhaust valve is opening. That increases the amount of hydrocarbons that are going out of the exhaust by not being burnt. And at the other end, on the valve overlap side [when the inlet valve opens before the exhaust valve closes], you have fuel that's being injected into the port and it's just completely skipping the combustion cycle and going straight out of the exhaust port.

“To reduce those hydrocarbons you do as much as you can with the catalyst, because that's a nicer solution and when catalysts are warm they get very high conversion efficiency. You can be easily over 95% conversion efficiency, which is great. But before they're warm you're really struggling.

“Valve overlap also does become a big issue, especially with more aggressive, high-performance engines, so you have to look at strategies for reducing it. That could be additional technology or it could be a lower state of tune for the engine. But because you can't accept any reduction in power you have to find other means of getting that power back.”

Paul Etheridge said: “Catalysts cost money and the bigger they are and the more precious metal they've got in them, the more expensive they are. And also, on motorcycles, the more difficult they are to package. So you want to improve the engine-out emissions as much as possible by improving combustion and optimising valve overlap, things like this, to minimise the emissions that come out of the engine. That also has a benefit in terms of driveability and fuel consumption.”

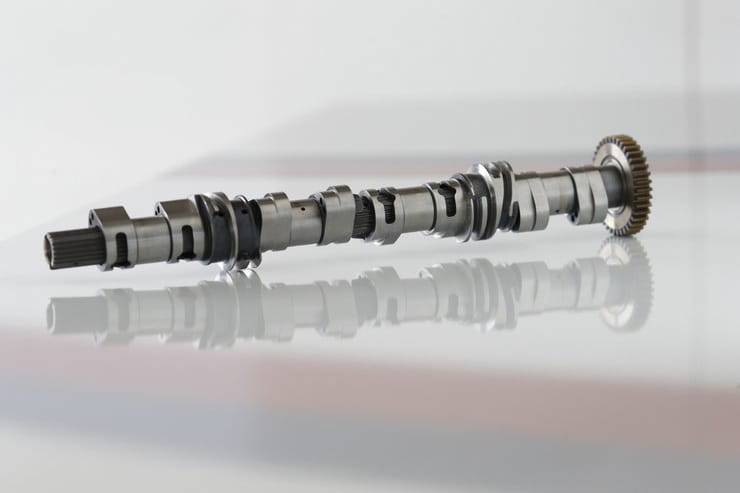

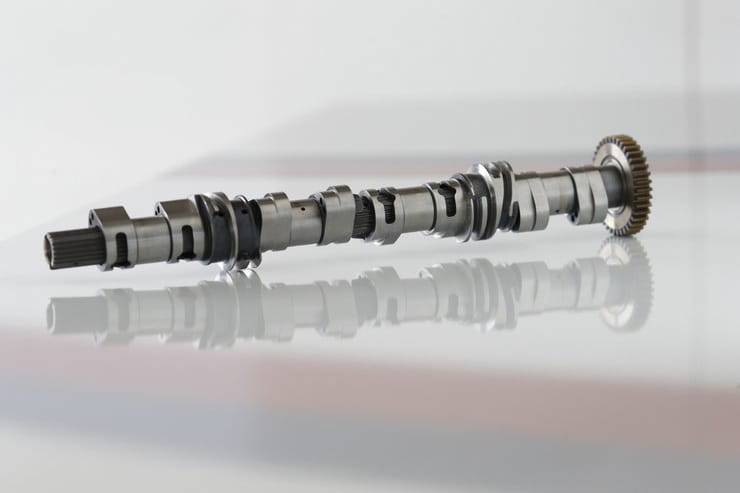

Variable Valve Timing set to spread

For high-performance, high-revving bikes, the rules seem perfectly tailored for a push towards variable valve timing technology. It’s already used on machines like the Suzuki GSX-R1000 and several Ducatis, and BMW’s all-new S1000RR one-ups them by using variable valve timing and lift. Etheridge said: “It's an enabling technology, and as with most things, you need something like legislation to get it into the market. Variable valve timing has got a number of benefits, not just enabling emissions compliance but also improving torque curve shape, driveability, combustion stability at light load, and fuel consumption. They're all positives for the performance of the vehicle. The negatives are, of course, it costs more and you've got to package it. But if you think about how motorcycle technology has developed, it's normally legislation that's forced the issue and then it becomes commonplace after a while and nobody thinks about it anymore. Take fuel injection, for example, and drive by wire. All these things have basically been forced on the industry by legislation but now you wouldn't do without them.”

Since variable valve timing and variable valve lift systems are such a panacea you might wonder why it’s taken so long for bikes to adopt them. Paul Etheridge says there are multiple reasons: “One thing is cost, and the other thing is that now automotive engines are downsizing the components are more readily available in the right physical size for motorcycles, which perhaps they weren't in the past. Remember turbochargers on motorcycles in the old days? They were horrendous things, much too big for the engines, they were waste-gated for most of the operating envelope of the engine and very difficult to control. But now turbos are fitted to little 600cc cars in Japan and they're physically the right size for motorcycles. The motorcycle industry alone never had the volumes that turbocharger suppliers would be interested in gearing up for. It's economy of scale. Now you can pick up a turbocharger off the shelf that's the right size for your 600cc or 700cc motorcycle, and that supplier makes millions of them for cars. They're cheap, they're physically the right size, and so then you can start thinking about an application using correctly-sized components. The same is true of VVT.”

Michael Ryland points out bikes also need more refinement than cars, saying: “One of the other challenges for VVT or VVL is the fact that motorcycles are much more sensitive to driveability issues. Because the inertia of the powertrain and the whole vehicle is so light, and there's a huge power-to-weight ratio, any small driveability issues will be felt by the rider very easily. It has to be refined very well.”

With leading superbikes like Honda’s CBR1000RR Fireblade and Yamaha’s YZF-R1 nearing the end of their lives, are we likely to see Euro 5 replacements bearing variable valve technology? Etheridge thinks so, saying: “I think for a situation like that, it's a no-brainer. For a superbike engine, you've got to have it for the future.”

However, he says different types of bikes will use different solutions to achieve Euro 5 limits: “The sort of work we've been doing for manufacturers is quite varied. We've been working on Euro 5 solutions for bike firms since 2013,” said Etheridge, “We've probably done 10 projects of various types, sometimes just looking at their current engine, telling them what they need to do to get it to Euro 5 and letting them go away and do that, and sometimes taking a project all the way through to producing a demonstrator engine with whatever modifications are most appropriate and delivering an engine back to them that has those Euro 5 features on it. We've been working on a number of different motorcycle types for a number of different manufacturers, so we've got a pretty good handle on what's needed for the various different types.

“If you look at the cruiser market, for example, it's all about look, so they have particular challenges; the exhaust has got to be visible so you can't just stick a big lump of a catalyst in the way; it might be great for emissions but from a look point of view it's completely unacceptable. For supersports bikes it's about maintaining or enhancing performance, while for smaller bikes it's about minimising the add-on cost. That's what we're helping people with today and we'll be continuing to help them until the legislation is in place.”

Michael Ryland adds: “Each type of engine has its own challenges. High performance engines are already really well optimised and they can't afford to lose any power, so to achieve an improvement in emissions they're looking at additional technologies. Whereas low-cost motorcycles have other challenges; they want to remain low-cost, so they can't afford to add anything that will increase the sale price of the vehicle. That means using the minimum amount of technology possible.

“One other solution, for high performance engines that aren't restrained to a particular capacity for race or road legislation reasons, is to change the capacity of the vehicle. You might have noticed that 600s are fading away but there's been a push in slightly higher-capacity middleweight bikes. A lot of the big manufacturers have increased the capacity of their middleweight bikes, allowing them to achieve similar levels of performance to before but without being so highly-tuned.”

Is Euro 5 a death sentence for some bikes?

While many bikes will be modified to meet Euro 5 restrictions, the new regulations will inevitably see some older models get discontinued.

Paul Etheridge said: “We know of some manufacturers who will not be re-homologating certain vehicles under Euro 5. The business case just doesn't work out: it's going to be too expensive to develop those vehicles to meet the new legislation, so they'll stop making them. Those sorts of decisions are happening.”

Michael Ryland says that the solution will be for manufacturers to have fewer different engines, but to use the remaining ones across a wider spectrum of bikes; “A few people are going to have to make the tough decision of dropping some of their engines for Euro 5,” he said, “So the approach they're going to have to take in the future is using one engine across a range of vehicle platforms because the development effort for the engines is increasing.”

Air-cooled engines are inevitably threatened each time there’s a new bout of emissions regulations, and Euro 5 is no different. But it’s low-cost air-cooled bikes that will suffer rather than big, expensive cruisers. Michael Ryland said: “It does make it more challenging so I think we might see a reduction in the number of air-cooled bikes. You can still get away with keeping things air-cooled, but it means you have to put more investment in other areas. If you take that decision from a styling point of view, or a strategic marketing point of view, then so be it, but it's probably not the most cost-effective solution for Euro 5 because you have to do significantly more calibration and development.

“The problem is temperature control. At the start of the test cycle you operate on a cold bike, so the warm-up of an air-cooled engine is going to take longer than a water-cooled bike with a thermostat that can close the flow of coolant to the radiator. In effect, as soon as an air-cooled bike starts moving, you've got 100% of the cooling, so it will take longer to warm up. Also, during the later stages of the test cycle, as the bike does warm up, it then isn't able to control the upper limits of the temperature either, so then it starts to produce more NOx as the combustion chamber reaches higher temperatures then the equivalent water-cooled engine.”

What about hybrids?

As cars have adapted to increasingly harsh emissions limits there’s been a rapid expansion of hybrids – using a combination of combustion engines and battery power to achieve better economy, emission and performance. But at the moment there’s little interest in the same technology from bike firms because they can achieve Euro 5 limits without resorting to hybrid technology.

Paul Etheridge explains: “You're going to need to have an electric motor and a combustion engine, and package it all in a suitable way for a motorcycle so you don't lose the fundamental advantages of the vehicle you're developing. What's the point? If you don't need it for certain requirement it doesn't make sense; it's more expensive, it's heavier. That may change in the future, but that's why you don't see many hybrid motorcycles currently.”

When it comes to pure electric bikes, he believes that the major manufacturers are showing much more interest in that technology now.

“The situation is changing,” he said, “We run a motorcycle technology conference once a year in Milan, and it was very clear to me this year that things are moving and changing now. The industry is waking up to this. I think that in the past few years, major OEMs have been sitting back and seeing what start-up companies are producing in terms of electric vehicles and how the market has accepted them, and whether they should get involved or not. It's clear now that people are picking up on this and starting to work on it seriously.

“What's not clear is what the most suitable technology is for different sectors of the motorcycle market. For inner-city, small, commuter-type vehicles, it's a bit of a no-brainer, electric propulsion is appropriate and does the job. But for bigger motorcycles, more premium leisure products, no one has got a clear answer yet as to which way they should be heading in terms of technology development. Harley has brought out the LiveWire, and there are other examples, but whether this is just to develop the internal knowledge base about electric motorcycles, or just a tester for the market, I don't know. But things are starting to move within the mainstream motorcycle industry.”

OBD Stage II headaches

When the EU rubber-stamped plans for Euro 5 back in 2013, a key requirement was the addition of OBD Stage II monitoring systems.

OBD – On Board Diagnostics – have been a key element of emissions controls in cars for more than two decades. They adopted OBD II way back in 1996. But while current Euro 4 emissions rules demand a basic OBD system that simply alerts you if an emissions-related sensor fails, the OBD Stage II setup planned as part of Euro 5 is proving to be a real headache – so much so that its implementation has been pushed back and remains under discussion at legislative level today.

Michael Ryland: “OBD Stage I looks at the key sensors or control systems measuring emissions that the bike produces, so anything on the intake, fuel system or exhaust. It just monitors to see if the sensor is completely broken - reading zero volts or at the upper limit. OBD Stage II looks at the voltage from sensors to see if they're at a sensible level, to see if they're giving a reasonable value, and on top of that you have to monitor a lot of the other emissions-critical items such as catalyst monitoring and oxygen sensor monitoring as well as engine misfire-detection. So you have to ensure that you're keeping an eye on these all the time that the bike is running to make sure that you don't cross the OBD emissions limit. It's a lot more advanced than OBD I, and a big step up for motorcycles, falling more in line with automotive.”

But why is a system that’s been around for so long on cars proving to be hard to implement on two wheels?

Paul Etheridge explains: “It's not simply carrying across technologies developed for automotive to motorcycles; it's more complicated than that. If you take misfire detection as an example, an automotive engine might rev to 6000rpm or 7000rpm, but it's a different kettle of fish when you're trying to monitor misfire on a motorcycle engine that's revving to 15,000rpm. So although the existing technologies may be appropriate, the application and calibration of those technologies is a lot more complex and difficult. A motorcycle engine is relatively low-inertia, and you get a lot of feedback from things like bumps in the road, which feedback into the engine through the driveline and can be detected as a misfire even though they aren't. So it's not straightforward and I think that's one of the reasons why this piece of legislation has been up for discussion and maybe some modification and delay in implementation, just because of the difficulties in applying it robustly to a motorcycle so you don't get a lot of false indications.”

Euro 5: the immediate implications

The clearest thing to draw from Euro 5 is that, with new models that go on sale on or after 1st January 2020 being required to comply, it’s going to be a huge talking point when next year’s machines are unveiled towards the end of 2019.

It means we’re going to see a proliferation of technology like variable valve timing and lift, and perhaps a renewed thrust towards turbocharged machines like the long-promised Suzuki Recursion.

However, the bigger hit is likely to emerge 12 months later, with existing models being required to comply from 1st January 2021. At the moment, there’s no word from the EU on whether firms will be allowed derogation – a period of grace to sell-off limited numbers of non-compliant old models. Under Euro 4, the EU allowed a two-year derogation period after its January 2017 enforcement date, which meant bikes like Suzuki’s non-compliant Hayabusa remained in showrooms right up until the end of 2019. No doubt there will be an increasing clamour for a similar arrangement under Euro 5 as its implementation date draws closer.

Find out about Bennetts bike insurance and, if you're an owner of more than one bike, take a look at our multi bike insurance which allows you to cover up to four bikes.