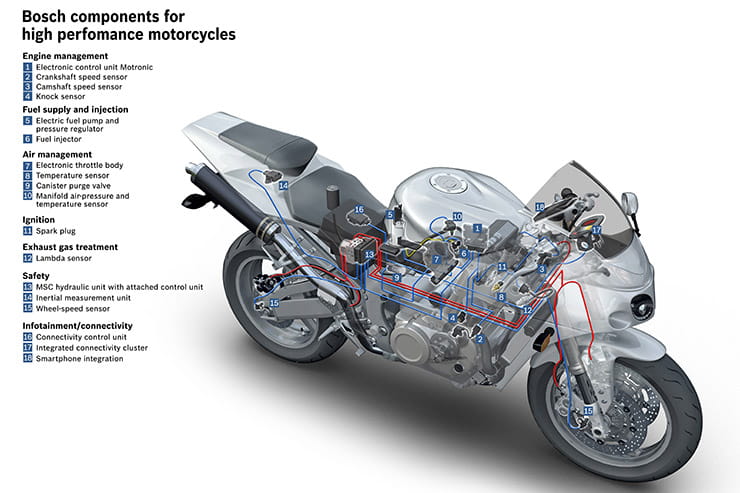

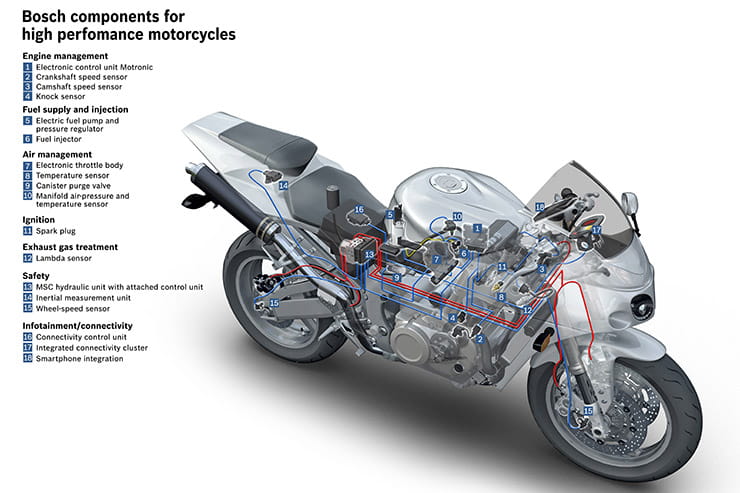

The ECU – Electronic Control Unit – is a bike’s electronic ‘brain’. As our human brain does for us, so the bike’s ECU uses an array of sensors to constantly monitor the status of three things:

- The engine: Things like water temperature, cam speed, crank speed, manifold pressure, O2 levels in the exhaust etc

- The outside world: Such as ambient temperature and inertial information from the bike’s traction control systems

- The rider’s input: Throttle, brake and gear position

It does this to ensure the bike performs the way the rider wants – within its design parameters – by issuing instructions to relevant hardware such as fuel injection systems and ignition timing. Basically, the ECU controls the engine – that’s why it’s called ‘engine management’.

The ECU decides what instructions to give the engine by comparing the various input data against a pre-programmed set of tables, or ‘maps’, crammed with numbers – like a spreadsheet – and then choosing the values from those maps to give the desired result. These numbers, or maps, are pre-installed at the factory, and are what the bike manufacturer has decided is the best (or cheapest, or easiest, or a combination of all three) for you, your riding, your bike, their bottom line and passing various environmental tests.

Which all sounds fairly straightforward – the ECU takes measurements on what’s going on and what the rider wants, looks it up, then fires out commands to make it happen. Clearly, this all happens hundreds of times a second.

But the ECU’s instructions are only as good as the information it gets from its sensors, and also having the right numbers in the tables. And this is where problems with standard maps and sensors begin… because what we want as riders isn’t always what the manufacturer actually gives us.

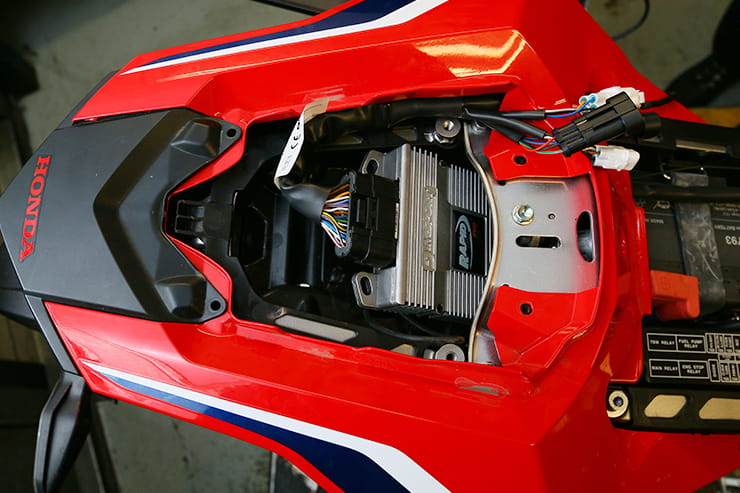

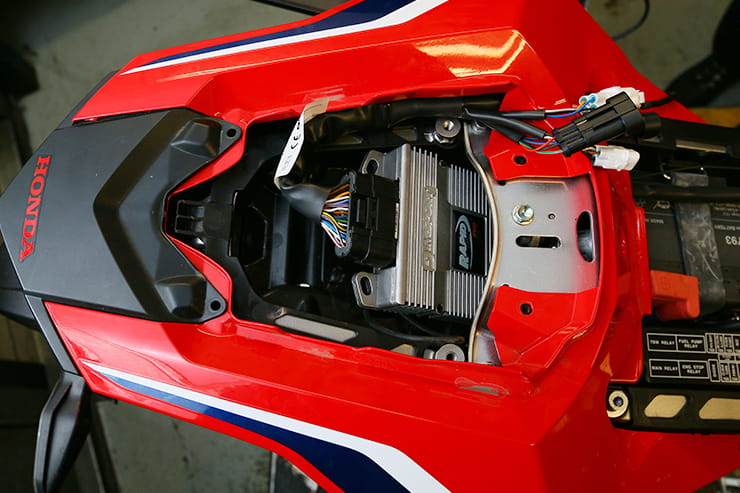

This is a standard ECU, made by Denso. Looks simple, doesn’t it?!

An ECU serves three masters: customers, accountants and environmentalists. It wants to make you, the customer, happy and give you the power and throttle control you want. But it’s also trying to keep environmentalists happy and maintain the engine within emissions test constraints. And it’s trying to do all this as cheaply, quickly and simply as possible, to keep costs down and the manufacturer’s accountants happy.

These demands are often contrary, and mean ECU maps are almost always a compromise. As riders, once we’ve bought a bike, we don’t necessarily care much about what the ECU mapping cost the manufacturer, how little time they had to get the programming right, and how many emissions tests the engine can pass. All we want is for our bike to feel nice to use and make as much performance as it can.

This is where remapping, or reflashing (it’s the same thing), or bolt-on modules like Power Commanders and Rapid Bike come in.

They’re two different methods trying to achieve the same thing – that is, adapting the ECU’s behaviour to suit us.

- Re-mapping is unlocking the pre-programmed software inside the ECU, accessing the various maps, and altering the numerical values to change the instructions the ECU sends out (it can also switch off various limiters and alter other parameters, and tell the ECU not to panic and show a fault code if it spots something out-of-spec).

- A module takes a different approach – it sits alongside the ECU and hijacks either the signals from the sensor inputs to the ECU, the output signals from the ECU to the engine, or both, and modifies them to give the instructions we want to give. It also has to ‘tell’ the ECU that nothing’s wrong to stop it showing a fault code.

An easy way to think of it is this: remapping is like having a foreign language downloaded into your brain so you can speak it fluently, while a module is like walking around with a translator instead.

Riding the clutch to try to smooth out an aggressive engine could be a sign you need a remap…

Two main reasons: first, you’ve got a criticism of your bike; the way the engine feels or the way it responds to your inputs. It’s usually a criticism of the throttle response; a common complaint is, “My throttle is snatchy and/or jerky, and makes me feel like I can’t ride properly.”

This problem is common to many new bikes and is usually most noticeable when you really want fine throttle control; at low revs, low speed and small throttle openings, such as using mini-roundabouts, or riding in town in the wet. It can be a subtle feeling, but often feels as if it can be broken down like this: you want a bit of throttle, open it slightly, nothing happens so you open it a bit more, then the engine responds suddenly with a surge. Or, sometimes, it can feel as if the engine is over-responsive and it’s hard to smoothly ‘pick up’ the throttle without a sudden snatch.

These are all good reasons for a remap or module.

The second reason you’d be looking to get a remap or fit a module is because you’ve modified the bike’s intake and exhaust system with an aftermarket exhaust and filter or airbox mod. This is normally looking for performance gains, although these days it’s just as much about improving cosmetics and reducing weight.

Either way, because you’ve changed the exhaust and/or air intake on your bike, the fuelling may need to be optimised to match the new, non-factory gas-flow conditions – this will optimise performance and the shape of the power and torque curves, and avoid any risk of engine damage.

Long story and several intertwined reasons, but the biggest culprit is emissions regulations.

Without getting too side-tracked into the details of how engines work, the bottom line of making an engine’s exhaust gasses ‘clean’ enough to pass emissions tests is, firstly, make them clean only where the motor needs to be clean to pass the tests. If emissions tests aren’t at full throttle and top speed (which they aren’t), then there’s no point engineering an engine to be clean under those conditions. It’s a waste of money and perfectly good bhp.

But if emissions tests are conducted at low speeds and revs, at partial throttle openings – usually simulating town riding, where pollution is the biggest problem – then that’s where the manufacturers put their efforts to make their engines ‘clean’.

The next step in making a clean engine is to make it a lean engine. A lean-running engine is one using a relatively high ratio of air to fuel – it means more of the fuel is burned, and more completely, and less gets into the exhaust and the outside world. The opposite – a rich-running engine – is using a lower ratio of air to fuel; it’s got more petrol in the mixture. Simple.

Except it’s not. Lean-running engines have lots of potential problems – they run hot, engine wear is more likely, combustion is harder to manage, and mixture ratio is critical to avoid engine damage. But none of these are insurmountable and they’re cleaner than rich-running engines, where fuel is sloshed merrily around to prevent these, and other, issues arising.

Another issue with a lean-running engine is managing fine throttle control. When an engine is running with a richer mixture, the transitions between fine degrees of throttle control are blurred and blended; the edges are rounded off. In a lean motor, those blurry transitions become sharp and angular – translating as an inconsistent, unpredictable or snatchy throttle.

I like to think of a rich (or normally fuelled) engine as a big, well-fed tiger. Offer it some fresh throttle meat and it’ll lazily take it from you. A lean-running engine is like a starving tiger – offer it some fresh throttle meat and it’ll have your hand off.

But it’s not just lean-running that causes a snatchy throttle. Another method of reducing dirty exhaust gas is to advance ignition – that means bring forward the point in the engine cycle where the spark plug actually sparks. Doing this extends the length of time the air/fuel mix has to burn inside the combustion chamber. Which means it burns more completely, which in turn makes exhaust gas cleaner. Unfortunately, advanced ignition also means the engine tends to feel over-responsive, so even small throttle openings result in a sudden take-up of drive.

The last reason modern bikes have snatchy throttles is the craziest. Hard to believe on a new bike, but some of them simply aren’t very good; the manufacturer hasn’t spent enough time (or money, or both) developing the mapping, and/or giving it sufficient fidelity or sophistication to be able to track a rider’s miniscule throttle position demands. Or the engineers simply put numbers in the maps that get the bike through an emissions test but, frankly, leave it fairly unpleasant to ride.

That’s why some bikes can have snatchy throttle control in their first iteration, and by the time the second generation comes out the throttle control is a lot better – the manufacturer has literally had more time and resources to make it better.

Throttle snatch varies from manufacturer to manufacturer. For example, KTM and Yamaha’s throttle mapping tends to be crude, while BMW and Ducati’s throttle mapping is more detailed and consequently much better.

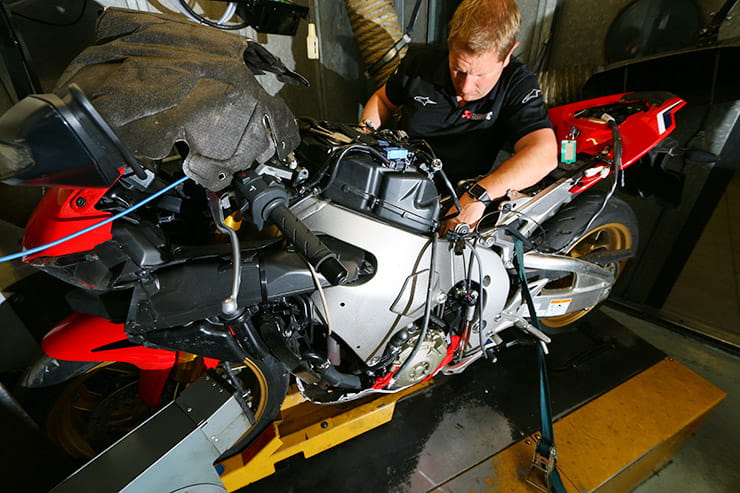

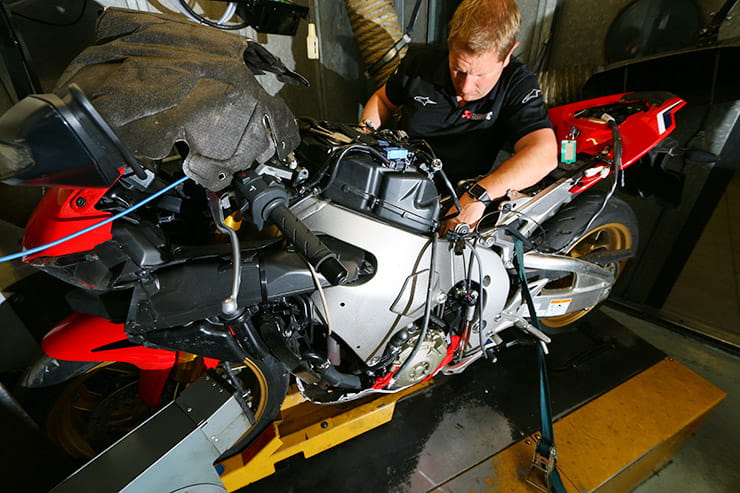

A professional remapper can change the way your engine performs

Depends who you ask; remappers – usually engine tuners with their own dyno and who’ve educated themselves in the intricacies of modern ECU programming – will say remapping is the only way to fully gain control of an ECU and bend it to your will. They also say they can alter parts of the ECU that modules cannot – for example, no module can currently access the ECU’s throttle map, which remappers say is vital for smooth throttle control on some bikes (for example, Yamaha’s MT-10 and various KTMs).

Meanwhile, module retailers will say visiting a tuning shop hundreds of miles away and having someone do brain surgery on your bike is unnecessary, and is also becoming increasingly difficult as manufacturers tighten up security of standard ECUs. Instead, all you need to do is to fit one of their plug-and-play boxes in the comfort of your own home to achieve the same result.

Both approaches have happy customers, though even the module manufacturers will often say that, to get the best results, their kit should be set up by a professional and reputable dyno engineer.

The pros and cons of each approach are straightforward; what matters is:

- What’s it cost?

- How convenient is it?

- How reversible is it?

- How effective is it?

The cost of a remap varies with the complexity of the bike. European bikes have a diagnostics port that can be accessed and ECU maps extracted and uploaded. It’s like a front door. Japanese ECUs are sealed off – there is a diagnostics port, but you can’t use it to get maps in or out of the ECU. Instead, the ECU has to be physically removed (which isn’t hard; it’s usually accessible) and spare pins on the ECU accessed in order to get in.

But overall, remapping access is getting harder and harder. Ten years ago ECUs were much more basic, the code was simpler, and remapping was straightforward. Many tuners and remappers could go in and change it themselves with a bit of experience, without needing any code-cracking.

Today, ECUs are so complex, remappers have to use third-party software to gain access – and even then that’s not enough. Ducati’s V4 Panigale took a long while to have its encrypted ECU cracked – it won’t open without a keycode. A software developer got round it and was about to release the software when Ducati found out and changed the keycode. So anyone who takes their (expensively) remapped Pangiale in for a service will find, when it comes out, the ECU has been updated, wiped, re-set to factory, and a new keycode installed. At the moment, no other manufacturer does this. But they certainly could if they wanted.

A basic, commonplace remap of a notoriously snatchy bike – like, say, Yamaha’s MT-10 – is a ride-in, ride-out job taking three to four hours (by an experienced remapper) and costs around £420. Some bikes, like big modern Ducati V-twins, are more complex and time-consuming (they have individual maps for each cylinder) and the job will be nearer to six hours and cost in excess of £500. A good remapper will also include a test ride in the job, to check their work.

A remap is reversible, but bear in mind you’d have to travel back to the place the work was done – as well as having to travel there and wait around in the first place. Good remappers aren’t in every town, so you might find yourself riding hundreds of miles.

Common sense would say if your bike is on the list of popular machines with obvious throttle and control issues, then a remap offers a more comprehensive and fundamental solution than a module, but may be less convenient.

Modules can be plug-and-play, but they’ll likely need to interface with several sensors around the bike

A module like a Rapid Bike or Power Commander can be ordered on the internet and delivered pre-programmed to your door. Most modules are plug-and-play – they clip into the bike’s existing wiring harness and no wire cutting or splicing is required – but installation simplicity varies depending on the complexity of the module.

Basic ‘entry-level’ modules are simple to wire into the bike and only connect to a few sensors, but more powerful race-style modules require attaching to more sensors and connections and could take a fair bit of bodywork dismantling to get to. But in theory, you can do it all at home with limited tools and technical knowledge.

But be warned – you will have to be able to read and follow an instruction manual which, as anyone who’s been to Ikea knows, is harder than it sounds. All modules are completely reversible and come pre-programmed with recommended maps. However, software can be downloaded that allows programming of the module at home; this is not always recommended because it opens up the potential for not only making the bike unpleasant to ride, but also possibly damaging it.

Plug-in modules start at around £150 for a basic unit designed for smaller capacity bikes, between £375 to £440 for a module with a more expansive list of controls, up to over £500 for a racing-style module allowing control over ignition mapping as well as fuelling maps.

The companies selling modules often also sell many other integrated electrical items: quick-shifters, racing dashes, Bluetooth mobile apps and more.

Most remappers – at least the honest ones – will admit a remap, on its own, won’t produce significant power or torque gains because that’s not the point; it’s about optimising fuelling to match a change in exhaust and intake, and/or making the throttle feel nicer to use. So the ride-ability of the bike is improved more than its outright power and torque. However, most bikes will show a slight improvement; some more than others, but not always.

Module retailers, on the other hand, are sometimes keen to suggest their solutions do make significant power and torque gains. Each bike is different, and some are said to respond better than others. In our experience with modern bikes, only mechanical tuning yields 'significant' power and torque improvements; fuelling and exhaust tuning tends to be more subtle.

It varies from bike to bike, but it’s never a massive difference. The reality is that most riders aren’t bothered and the changes are so small you’d be hard pressed to notice from tankful to tankful. Some riders will say they’re using more fuel, but a lot of the time that’s because they’ve ridden away with a remap or fitted a module and tend to use their engine a bit harder than normal to enjoy it.

It varies. Some bikes are so snatchy or crude to ride, the difference will be immediate and within a few seconds you’ll tell it feels better – smoother and more alive. On some bikes the improvement will be more subtle, and it might take a mini roundabout or wet weather to appreciate the improvement in throttle response.

It depends – nowadays on most bikes (but not all, you need to check!) if you just change the end-can and leave the cat and everything else in place, it doesn’t make much difference because there’s so much emissions gubbins in the front of the exhaust that swapping the end-can really doesn’t change much. It might not even be much louder, let alone alter fuelling as unlike older bikes, some modern end-cans are simply straight-through and use sound wave deflection into internal padding to add a final element of noise deadening. Older bikes had more pipework in the end-cans to help manage back-pressure tuning as well silence the engine.

Yes. This is common these days, to spare the cost of a full system but get similar benefits. A lot of de-cats require cutting the cat off at the headers, then sliding on a link pipe, although on a few bikes the cat simply slides off. This method will benefit from a remap or module, to get rid of flat spots and optimise fuelling.

Yes, it’s effectively the same as above.

Remapping is safe if it’s done properly, by a professional. Load the wrong maps into an ECU and you could brick it, permanently. And in terms of the engine, again, a professional install should be safe. But electronics are so powerful these days that it probably is technically feasible to set up an ECU so badly that it damages the engine. It’s also possible to set-up a module so badly it can damage the engine. But it’s worth noting a properly remapped engine ought to be theoretically more reliable because it’s running a safer air/fuel ratio.

In terms of a warranty, it’s a bit of a grey area and largely down to the discretion of the dealer. However, it’s worth noting some remappers actually get business from dealers who are tired of customers complaining about snatchy throttles and send them for a remap to shut them up.

I’m afraid so, yes. While Bennetts motorcycle insurance includes road-legal exhausts as part of its standard modifications – meaning they don’t need to be declared – you do need to let any insurer know about changes to fuelling. Don’t panic though as it just means the agent will need to check with the panel of underwriters to find a policy that suits you and your bike most so you’ll just need to call up to complete your quote.

This is slightly tricky because most of us have a tendency to want to believe something is authentic, especially if someone in a tuning shop with a bunch of wires and a screen says so. And even more if we just spent a few hundred quid. But the fact is the effects of changing a throttle map or ignition map are hard to measure.

But for evidence of actually having done something, a tuner should be able to show you the number changes to the maps. A good remap should be a fairly complex job and a good remapper should have plenty to explain to you. If you don’t understand it, keep asking until you do.

Something worth remembering is to be suspicious of big power gain claims from modules or remaps without further engine work; most remaps of modern engines don’t give big power gains, so anyone claiming they do should be treated with caution. Although some module suppliers happily claim gains, so you pays yer money...

It’s also worth noting that anyone claiming to be secretive or not wanting to give away a unique technique could well be hiding a bad job (or no job at all) – remapping isn’t magic and the chances of you deciphering a ‘secret’ are remote anyway. Someone trying to hide something usually has something to hide, so be suspicious.

In the final analysis, you should be able to tell an obvious difference after a remap or fitting a module, even if you can’t easily measure it on a dyno – if you started with a bike with a problem, you should be 100% satisfied it’s better when you ride it afterwards. If the differences are so subtle you’re left wondering if it’s better or not, alarm bells should start ringing.

Word of mouth is a good place to start, but it’s not a guarantee – some remappers have had amazing reviews right up to the point they’re rumbled as being fake. In the end it comes down to having your bullshit radar on – read the remapper; if he looks and sounds like a wide-boy chancer, is evasive or secretive, tries to blind you with science or makes outlandish claims, walk away. Modesty and humility go a long way in the remapping game.

Thanks to Andy at BSD Performance in Peterborough for help and information compiling this feature. BSD offers a full remapping and race-tuning service, as well as numerous other bike services. They’ve been in business for over 20 years serving race teams, dealers, manufacturers, the press and the public alike. Their reputation is second to none.

BSD Performance is based in Eye Green near Peterborough (01733 223377 or bsd.uk.com)

Thanks also to Liam Johns at Rapid Bike, c/o Performance Parts ltd. Rapid Bike makes a full range of tuning modules of differing levels of sophistication, covering all sizes of bikes for all riding applications, from commuting to touring to racing. Visit the Rapid Bike website for more information.