A newly-published ‘British Social Attitudes Survey’ from the Department for Transport shows that the country’s distaste for speed cameras is ebbing away – with a growing majority now believing that they achieve their aim of saving lives.

It’s quite a turn-around compared to the early days of the technology, when the sight of burnt-out Gatsos was a common one and vocal anti-camera campaigns worked hard to get their messages heard.

But, more than quarter of a century after the first Gatso camera was deployed in the UK – on the A361 at Twickenham Bridge back in 1992, in case you were wondering – is the public right to put its faith in the technology?

Growing support for speed cameras

The new survey reveals that, as you might expect, the vast majority of British adults agree with the statement “People should drive within the speed limit.”

In fact, 91% of respondents agreed, and that’s a figure that’s largely unchanged since 2005 when the annual survey first posed that question. However, the attitude towards speed cameras has swung in their favour over those years.

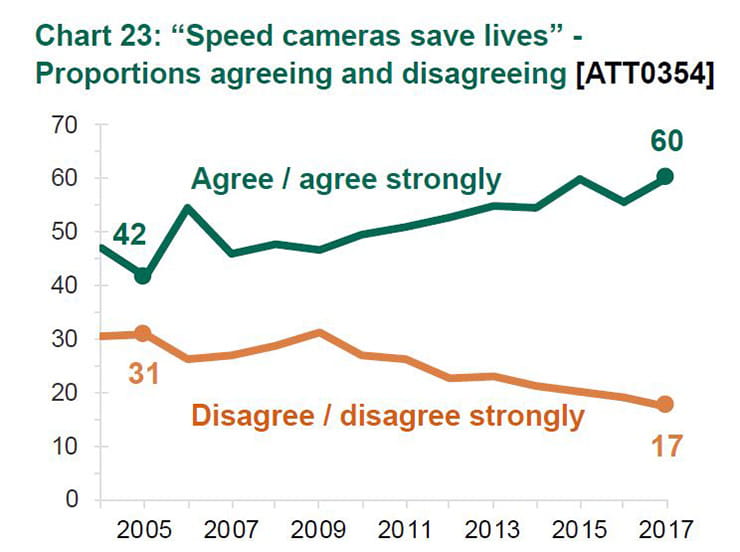

In the latest survey 60% of people agreed with the statement ‘Speed cameras save lives”. Back in 2005, just 42% thought that was the case. Over the same period, the number actively disagreeing with that suggestion has dropped from 31% to just 17%. Around a quarter of people don’t have an opinion either way.

But is it really true? While it’s easy to get bogged down in a quagmire of statistics, over the last few years the number of fatal accidents in Great Britain in which exceeding the speed limit was reported as a contributory factor has remained fairly steady. Unfortunately, figures measured in their current form only extend from 2011 to 2015, but since overall fatalities have generally declined over that period, the proportion of fatalities where speeding is a factor has risen. In 2011, speeding was involved in 12.8% of road crash fatalities (and 6.5% of combined fatal and serious injury accidents). By 2015, the most recent available figures, 15.1% of fatal accidents involved speeding, which played a role in 7.4% of fatal and serious injury accidents. It’s a small increase, but the rise has been fairly steady over the intervening years.

When it comes to motorcycles, exceeding the speed limit is more likely to play a role in a crash. Speeding was a factor in 4.7% of all bike accidents involving an injury in 2017, compared to an average of 2.7% across all vehicles. When it comes to fatal bike crashes, speeding played a part in 22.3% of them in 2015, up from 16.5% in 2011 but a drop from a peak of 26% in 2013.

Making sense of the statistics

Do all those statistics mean that mean the statement “Speed cameras save lives” isn’t true? Without knowing how many accidents there might have been without speed cameras, it’s impossible to say with complete certainty. But we can show that there’s been an increased reliance on speed cameras over those years and that there hasn’t been a simultaneous decline in speeding-related accidents or deaths.

In 2011 there were 739,000 fixed penalties handed out for speeding, 600,000 of them were detected by cameras. By 2015, the number of fixed penalty notices had increased to 791,000. Over 730,000 of them were courtesy of cameras, while only 60,733 were ‘detected otherwise’ – presumably by real, living police officers.

The number of speeding offences that went to court rather than being dealt with by fixed penalty is also rising steadily, from 123,000 in 2011 to 180,000 in 2015, although the DfT statistics don’t break down how these – presumably more serious – offenders were caught.

Overall, speeding convictions have grown from 851,000 in 2011 to 958,000 in 2015.

That growth – around 12% – is roughly in line with the increase in fatalities and serious injuries attributed to speeding. It outstrips the overall increase in motor vehicle traffic over the same period (which is 6.5%).

These figures also disguise a vast increase in the number of people caught – usually on camera – who opt to take a Speed Awareness Course rather than a fixed penalty or a conviction. In 2016, 1.2 million drivers took these courses, a rise of over 50% since 2011.

Strangely, despite the increase in speeding fines, the rise in numbers caught by cameras, the vast explosion of Speed Awareness Courses and the growth in fatal and serious accidents involving speeding, research shows that the proportion of vehicles speeding is actually falling. Using roadside surveillance it was found that 49% of cars exceeded the speed limit on motorways in 2011, a figure that dropped to 46% in 2016. In 30mph limits there was a similar decline (from 55% to 53%) and in 60mph limits the figure has been steady at a relatively low 8% ever since the current system of measurement started in 2011.

More cameras coming?

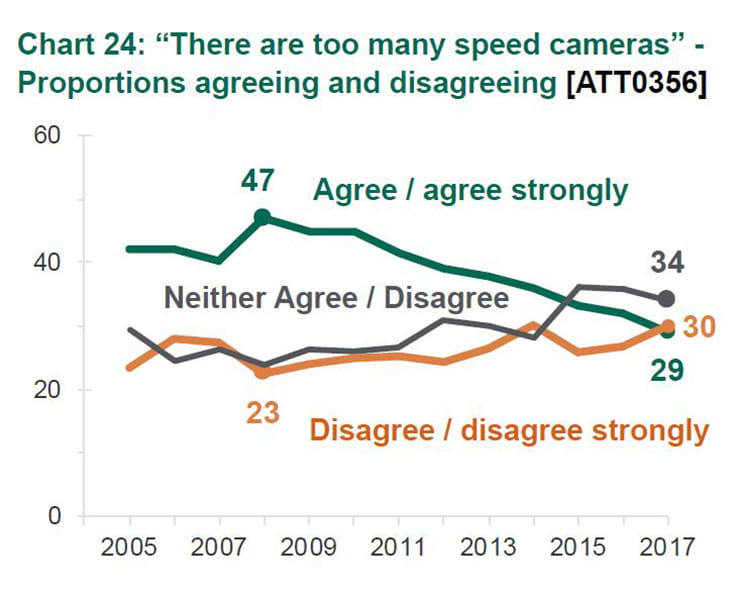

The new Social Attitudes survey’s questions on speed cameras didn’t end there. Next, respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement: “There are too many speed cameras”.

Back in 2008, 47% of people said there were too many, but over the last decade the numbers have fallen and now, for the first time ever, a greater number of people disagreed with that statement than agreed with it.

In the latest survey, just 29% of respondents said there are too many cameras, while 30% disagreed – suggesting they think there are either the right number or that there should be more of them. The neutral position – neither agreeing nor disagreeing – has become the most popular stance, though, attracting 34% of the vote.

Speed cameras and revenue

Despite the apparently increasing acceptance of speed cameras, one thing remains constant – the dominant view of them is that they’re there to raise money more than anything else.

Faced with the statement “Speed cameras are mostly there to make money” by far the most popular response was agreement. In the latest survey, 42% said that was the case, while only 27% disagreed.

But that still represents a growing acceptance of the cameras. Back in 2004, 58% of people agreed with the same statement and just 22% disagreed. The biggest growth is in the ‘don’t know’ group, which accounted for just 16% in 2004 but now takes 26% of the responses.

In terms of camera technology, there’s a surprising – but perhaps sensible – preference for average speed cameras over fixed speed cameras, with 55% saying the average speed cams are better.

Other findings

The DfT’s British Social Attitudes survey didn’t just focus on speed cameras, though. It also looked at a host of other concerns for road users.

Key changes compared to earlier surveys include an increased number of people agreeing that car users should be taxed more heavily for the sake of the environment (27% agree, up from 12% in 2004). The message about driving while using handheld phones is also getting through. While a steady 90% have believed it to be unsafe over the last decade, the proportion that ‘disagree strongly’ with the statement “It is perfectly safe to talk on a hand-held mobile phone while driving” has risen from 56% in 2007 to 70% in 2017.

It also shows that drink-driving remains a much-despised habit, with a steady 85% believing that “If someone has drunk any alcohol they should not drive”. Meanwhile, a majority (47%) are in favour of speed bumps on residential streets, while only 30% are against them.