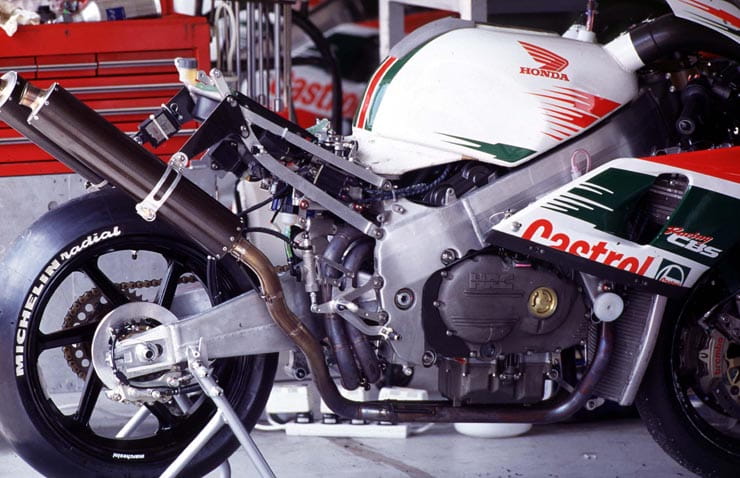

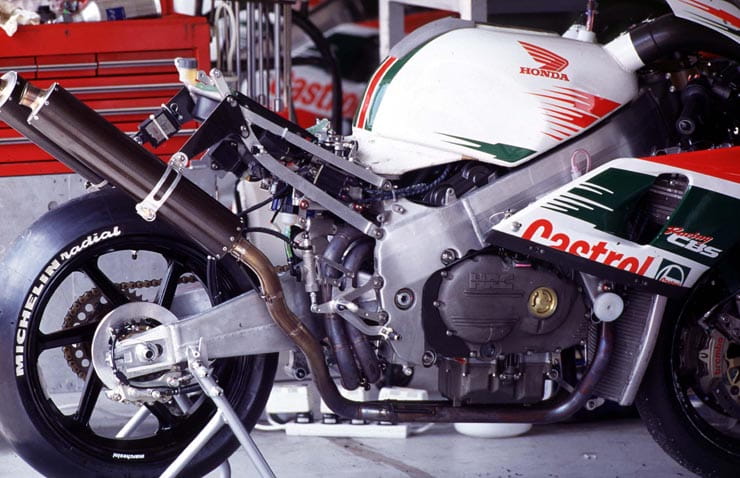

There aren’t many men like Aaron Slight. Anyone watching World Superbike racing at its peak in the 1990s would be familiar with seeing the hard-boiled Kiwi wrestling a recalcitrant green and white Castrol-sponsored Honda RC45, up against a sea of Ducatis that had the rules so biased in their favour it was almost legalised cheating. Runner-up to the world title twice (once losing by 4.5 points) and third on four occasions (including one for Kawasaki), no-one came closer more often, and gave so much, without lifting the title.

But that’s only one reason Aaron Slight is special. Another is he’s one of the few riders to campaign a factory bike from start to finish across its entire racing career. Slight took the RC45 to the podium for its first race in 1994 at Donington, and he rode it for its last race in 1999 at Sugo in Japan six years later. No-one is better placed to give BikeSocial an insight into the ups and downs of life on Honda’s iconic V4.

BikeSocial: When and where was the first time you set eyes on the RC45?

Slight: The first time I saw the bike was at Phillip Island for the first test in 1994. Doug Polen, the reigning World Superbike champion, and I arrived and the bike was just in a plain white livery. We pulled the bike out of a crate and started riding it. At the time I was the lap record holder at Phillip Island, on the Kawasaki ZXR750 – it was a 1m 38.3s – and I managed a 1m 40.1s on the new bike. Two seconds slower. My first thought was like, ‘What the hell have I done?’

BS: So it wasn’t a great introduction?

Slight: I suppose I expected a bit more from Honda. The main let-down was its engine. It wasn’t fast enough out of the box. Everyone thinks Honda have a good top speed, their bikes have always been fast. So I thought I’d be half a second off. And also Doug Polen was a second and half, maybe two seconds a lap slower than me, so he was four seconds off.

But once I got a look at some components I started to wonder maybe Honda hadn’t put their best foot forward. I looked at the shape of the pistons and they were unfinished, not like race pistons. There looked like a lot of work still to do. So at least there was room for improvement; things could get a lot better. When I thought about it I wasn’t too down. I think basically Honda underestimated the opposition. Since the RC30, Ducati had moved on a lot by going with a bigger engine, bigger engine and bigger engine.

And from one point of view, at that first ride at Phillip Island the bike had amazing handling because the motor just didn’t have enough horsepower, enough grunt. Once it got some grunt, then we got into all sorts of handling difficulties.

BS: A lot has been made of the RC45’s handling issues over the years. Some riders say it was the best thing ever, some couldn’t ride it.

Slight: I guess the trouble starts when riders don’t actually know what they want; and every rider’s different. So like when Carl Fogarty joined the team in 1996 he said the bike was designed around me; well, the truth is it was a production bike and I rode it, and I used to have to put my weight in weird places to make the thing turn. So because we couldn’t chop the chassis to solve those problems and make it better, I had to adapt my style to something that would work on it.

We weren’t allowed to alter the swingarm pivot position within the rules because the road bike didn’t have it. At Kawasaki we had an eccentric for the swingarm pivot point, but we never did that at Honda. We mucked about with swingarm linkages and lever ratios all the time, but we never changed the headstock geometry either. We did have eccentrics in the headstock, but we never changed it because it never got rid of what we were trying to get rid of.

I remember one year we tried six different single-sided swingarms, trying to get the right rigidity – sideways as well as flexibility upwards as well. That was just to get a better feel and make the tyre last longer. And then we started mucking about with twin-sided swingarms in the rear which we thought might preserve the tyre better than a single-sided swingarm. And it worked! One test at Phillip Island – it was a major winter test track for us, and it really wears the tyres because it’s such and abrasive surface – we found with a double-sided swingarm we could get the tyres to last a lot longer. The idea was we could make it less rigid, rather than that single big piece of aluminium. Even the way the wheel bolts into the arm, which that huge nut – with an axle, you get a bit of flex there too.

BS: You were famous for that style that had you hunched over the front of the bike, with your elbows out...

Slight: At the start we were on Dunlops because that was the deal with Doug Polen. Honda wanted to race on Michelins but Doug had said he wouldn’t sign unless they were on Dunlops. So they were going away from what they knew: the factory RC30 was always on Michelins.

But for the first season the bike actually worked well on Dunlops; there was a good feel with that tyre. But in 1995 Doug left the team and we went to Michelins; and then we really got lost. In the early 90s the Dunlop front was so useable and feel-able you could just about do anything and not lose it. And a lot of people couldn’t use the Michelin and it even ended careers. So the problem with the RC45’s handling got a whole lot worse. The Dunlop was pliable and the Michelin sidewall was firm and didn’t give you much warning. So there was a big nothing feel. And so sometimes you didn’t have the confidence to turn it underneath you because you couldn’t feel it.

So that’s when I developed the style of riding right over the front of the bike, getting a lot of weight onto the front tyre. The more weight we put on the front, the better it turned. And as long as you kept the front loaded it’d turn really good.

By then our engine had a lot of horsepower but no torque, so we’d get a lot of wheelspin. You always knew in the back of your mind that by the end of the race you were gonna have degraded tyres way more than the other bikes. And you knew that was going to be your problem. And that’s what I became known for, for managing the package until the last five laps of the race because that’s when the race was, really.

BS: So you had a good bike but were overriding it so much to live with the twins you were running into problems you should never have faced?

Slight: You hit the nail on the head there. Even with my teammates, Doug Polen, a world champion, Carl Fogarty, a world champion, John Kocinski, a world champion – Honda were trying everything; they picked a world champion after world champion as a teammate, just in case I wasn’t doing the job. And we’d come up with the same old same old. It was really hard to win a race on something that was so stretched to the limit of the regulations.

BS: Your time on the Honda seemed to be a never-ending battle against the rules, with the twins allowed to run at 1000cc compared to the Honda’s 750cc. How did it feel at the time?

Slight: The bike was incredible but we were chasing something that wasn’t in our league. At the time, you’d go to a racetrack and you’d talk to Carl or somebody on a Ducati and they’d change the final drive sprocket. We’d go to a racetrack and have six internal ratios to change, three primaries, you know, we had it perfect for every corner. And they’d turn up and go, “Oh, I think I need a couple more teeth on the back.” You know? You’d say fuckin’ hell, how does this work? On our bike you couldn’t come out of a corner and have it really doughy because you’d lose too much time. Where on the twin it was easy to just chug away. Which we really noticed when we had a V-twin!

BS: Did you ever get a sense of Honda being fatally wedded to the V4?

Slight: I actually think it was about Japanese culture. They’re very honourable people and once they set themselves a goal, they’re gonna beat you at it. They’re gonna work their butts off to make it work. They’re not gonna sit back straight away and go and build something else.

So it’s a Japanese culture thing – once they’ve gone down a track they like to stick to it. It took a lot for Honda to build the V-twin. And if the Firestorm hadn’t been a success they might not have done it anyway. You know, they said ‘See how it goes on the road,’ then, ‘Oh shit, everyone’s buying it, let’s do more.’ And the Firestorm, and even the SP-1, weren’t anything like the RC45. Look at the price of them; they weren’t as high tech or high dollar as the RC because it showed you didn’t have to be to run at the World Superbike V-twin regulations.

I was the development rider for the V-twin, and I was at Suzuka in 1998 when they made the decision to go with it or not. I was riding the bike and it was up to me whether they made a race bike out of it or not. I followed Itoh, their Japanese test rider, around; he was on the RC45. I was on, like, a Firestorm. The chassis was shit and I was 23kph slower in the straights. But I got a tow off him and was only half a second slower. I said it feels slow, but if it feels like this but is so close, we’ve gotta do it. There was no other choice.

And then to go and do it and win in the first year, which Colin did, it shows you where the competition was and how the rules worked.

BS: Did you ever wish Honda used a V-twin from the start?

Slight: Nah, I don’t like riding a V-twin. A screaming four cylinder is the only way to ride. It’s a bit like when they banned two-stroke motocross bikes: everybody can ride a four-stroke, but not many people can ride a 500 two-stroke. And I felt a bit that way when Honda got their V-twin, you know? Because they’re so narrow and change direction so easily, and they’ve got the extra capacity and that easy power delivery; anyone can ride one. I loved the screaming of the engine and the wheelspinning of the high-revving fours. When we first got the V-twin it only revved to 10,500rpm and we thought, what the hell’s wrong with this thing? If we didn’t have a stop watch, we wouldn’t have picked the V-twin to race, because the four is so much more fun. At first we thought shit, this thing’s not too good, but the stop watch says it’s amazing.

I don’t know how many people came up to me after the launch of the Firestorm and said this is just the perfect bike, I was scared of riding a 1000cc inline four but these are so easy to ride. So that gives you the answer: they’re easy to race too!

But I liked spinning the back wheel. You know, I still believe when Ducati got Ferrari to design the 750cc inline four for the MV Agusta; that was going to be Ducati’s World Superbike. But then they put it on a dyno and said, why would we bother? We can make a V-twin for half the price. So they carried on with the V-twin getting bigger and bigger and just put an MV Agusta badge on the 750.

BS: What power did the factory RC45 make?

Slight: I’m not sure what the power was at the start, but by the end in 1999 it was in the 193bhp region. But the very last ride on the RC45 was in the last round in 1999 at Sugo. Honda turned up and the bike had a new crank in it. I thought, ‘This is its last ever race. What’s going on here?’. A new crank, another few horsepower, and so I think that was the start of the development for the four-stroke MotoGP RCV bike, back in 1999. If you divide 750 by four and put another cylinder on it... you’ve got your GP bike. So I think they were thinking about four-stroke Grand Prix back then.

It was going that way. Honda was so involved in superbikes. I rode the NSR500 pre-season in 1995, and I pushed hard to get a ride on one. And they said to me at the end of the day, ‘Doohan gets paid a lot of money, Criville brings a lot of money, and we pay you a lot of money in World Superbikes. There’s no money for you to go 500s so take your pick.’

BS: Was the RC45 a strong engine?

Slight: The motor was really reliable. I had a few issues, which I was told at the time not to say anything about. A couple of times it threw me off – and I’d get the blame on the TV for it, but I was told not to say anything about it. There was one in 1998 which everyone saw, at Monza, when the thing just let go and caught fire with one lap to go. That was the year I lost the championship by 4.5 points, and to lose 25 points on the last lap like that at Monza... it was put down to a bad batch of con-rods; we didn’t use any from that batch again and we never had another problem. It was just unlucky. The quality control was always really, really good – and everything had mileage limits, chains, sprockets, everything.

People think in a factory team you just bolt stuff in and out but we didn’t. Everything had a life. We didn’t just bolt engines in and out. You might pull down an engine and even re-use the same rods and pistons, just put new rings and valves in. We never used a whole new engine all at once. It had an optimum running time and was changed accordingly. It amazed me. I used to think well, you’ve got the engine apart, you might as well use new parts in it. There was no rule against it. But they didn’t. They were like, well, it’s run in now, might as well keep using it. Leave it alone. But because we were using a different gearbox every weekend, and that meant the cases had to be split, the engine was apart all the time. You could’ve put anything in it you wanted to.

BS: Which year was the best RC45?

Slight: 1998 was my best season. Everything gelled that year. We’d had 94, 95... in 1996 the bike was still coming right. 1997 was going to be good but it rained all year. John Kocinski won the championship, but it was about wet weather riding. Then in 1998 I was at my optimum, the bike was at the end of its development life so it was the perfect RC45. Or it was the perfect 750, put it that way! It did everything I wanted, and I knew what it was going to do before it did it. In 1996 we went to Misano and I had a 16th and 18th on the Michelins. In 1998 I had a double victory there, so we obviously sorted it out.

And that day I felt like I had the thing perfect and had the opposition sussed. But in that year it dropped a rod at Monza, I fell off it at the Nürburgring while in second and finished fourth, you know, was involved in a crash on the start line at Laguna Seca – a whole lot of things went wrong but I still won more races than Carl that year. It just felt like I was riding it really well and had the smarts on the opposition – they still had the better package but I felt I could out-ride them – and it was perfect.

But in 1998 I was already developing in the V-twin, test riding it in Japan at the same time as racing the RC45, so I knew the RC45 was coming to an end. So in 1999 the bike didn’t really go anywhere for me, I think.

BS: So that must’ve made 1999 a difficult year to motivate yourself?

Slight: Yeah, well I had a few health issues as well [Slight suffered health problems all year, finally suffering a stroke while surfing in winter 2000. He returned to racing in 2000 for Honda on the SP-1 but never recaptured his form]. But yeah, it was tough. Having ridden Honda’s V-twin in testing, you suddenly knew what it was you were racing against all these years, how hard it was. And we still had to beat our head against the V-twins. So that was a hard season.

BS: Have you got an RC45 now?

Slight: I’ve got a brand new RC45 in a crate. Back in 2001 the last 13 of them were being sent to England and the four top Honda dealers got three bikes each, so there was one left and I purchased it. It’s out in the shed, still in the crate. I was never a road rider anyway; I raced motocross and then road raced. When I won the 8hr for Kawasaki I got a ZXR400 replica of my ZXR750 race bike. So then when I won on the Honda I asked for a 400 version of that, so I’ve got an NC35 as well. I’ve got them both in my trophy room – I put them in there to see if I had room for the 45, but I never bothered to get it out of the crate. It sort of means a whole lot more to me just sitting there, knowing that I’ve got it. One day I’ll pull it out – I’ve lifted to top off a couple of times and looked at it.

BS: To come so close so often; do you have any regrets about your time in World Superbike?

Slight: I had an opportunity to sign with Ducati halfway through my career with Honda. I had talks with them, but I like the way the Japanese work. I liked having a contract I could understand, I liked things sorted at the start of the year. And I liked knowing what was going to happen rather than someone saying yup, I’ll think we’ll do this... I needed confirmation. I was a little guy from New Zealand travelling a long, long way and I wasn’t gonna go on some Italian’s word, that this is what we’re gonna do for you. I always stuck with the devil I knew and have no regrets for being there. From here, in New Zealand, to World Superbike? I had a great time. I never won the championship and that eats me a little bit, but I wouldn’t change anything.

BS: And how do you feel about how it ended?

Slight: Having the brain bleed made it easier for me to retire from racing. People never really retire from racing, they either get injured or slowly get slower – so for me, looking back, I had a decent excuse! It made it easier to bow out. And who manages to do that? Why would you stop while people are patting you on the back and paying you lots of money? There’s no reason to stop. So you get to the likes of Frankie Chili and you could see it in his eyes: ‘Next year’s gonna be the year...’. But you’re just getting older and getting slower. Someone like Colin Edwards; you know, just stay at home! It must be hard for them. You gotta reach a time when you’ve no regrets and just do it.

BS: What’s life for Aaron Slight like today?

Slight: We came back to New Zealand in 2004 after staying in Monaco for a while. We’ve got a little girl who’s seven, so that takes up time. Kids are only little for a short while so if you can be around, be around. I’m involved with a whole lot of investments for myself out here, but I still have an alliance with Honda in New Zealand so I’ve got an ambassadorial role with them. It keeps me involved. I do driver training as well, for Aston Martin, Lamborghini and Bentley. And I’m involved with my father’s business; he had a small hardware shop and we’ve just made it into a bigger place, a bit like B&Q. It’s called Mitre 10 Mega.

I’d like to be closer to the action in Europe, but every year I was there I was only ever on a one-year contract, so I never really made Europe home; I was only ever going there for the racing and then I’m returning home. So when it came time to stop I was like what do I do now? So I decided to come back to New Zealand. But to be honest I can’t be bothered with the travel.